Cross-border co-operation has the objective of reducing the effects of barriers, including administrative, legal and physical barriers, that are found at borders. Local and regional authorities and organizations co-operate across borders to promote regional development by improving infrastructure and public transport, by managing and monitoring common cultural and natural heritage and by reducing border obstacles such as differences in national regulation in order to facilitate mobility across borders.

Transnational co-operation covers a larger geographical area and might often have a wider and a longer-term scope than cross-border co-operation. Both cross-border and transnational co-operation are important instruments to bring ‘added value’ to regional and local development. In addition, it is an instrument to achieve the overall EU aim of economic and social cohesion across the EU because its aim is to address common problems and exploit unused potential across the borders. Working towards a Territorial Agenda has been one of the core fields of European collaboration. The objectives of the agenda has been to reduce existing disparities, avoid territorial imbalances, make all policies with a regional impact more coherent and improve integration between the regions of the EU. The revised Territorial Agenda (2020) also makes an important contribution to the debate.

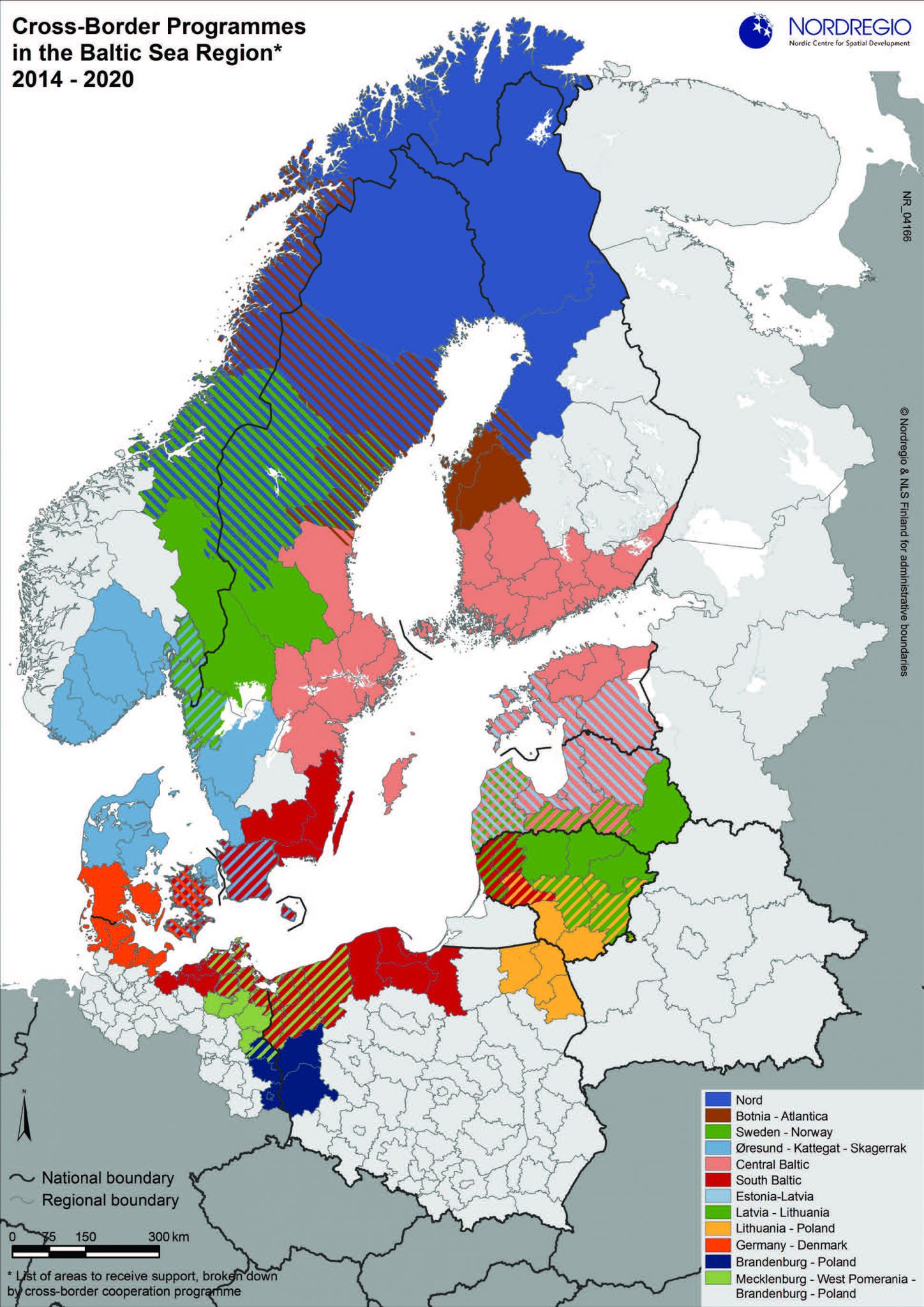

Within both Nordic and European co-operation lie a wide range of programmes and co-operation activities across the borders. Some of these activities, such as Nordic cross-border committees, have longstanding traditions; others are a continuation of previous programmes, e.g. European Territorial Co-operation programmes; and some are relatively recent, among which is the Baltic Sea Region (BSR) Strategy. The cross-border co-operation activities and programmes vary in geographic scope, available funding, themes, political grounding and backing. Cross-border co-operation can be viewed as a multilevel approach to regional development, as it involves actors at different levels building co-operation with an overarching goal of contributing to regional development in border regions.

The evolution of cross-border co-operation

In a European context, the first Euroregions (defined as transnational co-operation structures between two or more neighbouring areas in different European countries) were established in the 1960s but it was not until the 1980s that European institutions began to financially support cross-border co-operation. The deepening of the European Integration process opened the way for EU incentives to be provided for better integration in border areas. With the deepening of the European integration process, regional development has become one of the core activities of the EU as it contributes to achieving the overall EU aim of economic and social cohesion across EU regions and reducing regional disparities. In 1990, the Interreg initiative was launched as an instrument to support cross-border and transnational co-operation. Over the past 25 years, Interreg – officially, European Territorial Co-operation (ETC) – has become the key instrument of the EU to support cooperation, exchange and networking between partners across borders. In addition to the ETC programmes, the EU has set up a number of programmes focusing on co-operation along the external borders of Europe: The European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) is considered a framework for co-operation between regional and/or local authorities on both sides of the EU external border .

In the Nordic countries, cross-border co-operation between adjacent municipalities and regions has a long tradition, dating back to the 1960s when transnational co-ordination organizations were established to enhance integration among the Nordic regions. There are currently 12 Nordic cross-border committees located throughout the Nordic region, which work towards enhancing growth and development in the cross-border regions. The prerequisites for Nordic crossborder co-operation have changed due to investments in infrastructure (the clearest example being the Öresund Bridge between Sweden and Denmark), changing consumption patterns (border shopping has become an increasingly important source of income for many towns in Sweden located close to the border with Norway) as well as changes in attitudes when it comes to working and living in neighbouring countries. In addition, the introduction of the Interreg programmes in the Nordic countries when Sweden and Finland became members of the EU has had an important impact on cross-border co-operation in the Nordic context.

What is the added value of cross-border co-operation?

There is an assumption that transnational and cross-border co-operation can bring added value to regional and local development and ultimately enhance European territorial integration. The added value of a policy or a programme involves a discussion of the need for such an intervention, i.e. its rationale and relevance, and its effectiveness in reaching its stated objectives. The concept of added value has been widely discussed in EU cross-border and transnational programmes. Four main types of added value of cross-border and transnational cooperation can be identified: solutions to common problems, learning opportunities, generating critical mass and building structure for further co-operation and territorial cohesion.

Cross-border co-operation can be very hands-on when there is a need to co-operate to solve a problem that is common to a particular area. This can be seen in the co-operation between countries around the Baltic Sea, concretized in the EU BSR Programme under the ETC objective. The BSR programme most specifically supports projects that focus on solutions to shared problems. This is also reflected in the priority area of the Baltic Sea, which is seen as a common resource. The work of the Nordic cross-border committees is also guided by the same principle. For example, some of the committees covering the peripheral areas are addressing issues related to depopulation, unemployment, infrastructure and other challenges that are relevant to a specific border area. A practical example of solving a common problem – a lack of medical personnel and long travel distances – is the co-operation between municipalities when it comes to providing emergency services across the Swedish–Norwegian border but also between Sweden and Finland. Cross-border co-operation is also recognized as an important platform for exchange of knowledge and opportunities for policy learning across borders. This type of added value is emphasized both in previous and current ETC programmes. One challenge for the ETC programmes is to concretize the learning processes and find tools for measuring and evaluating learning across borders. For instance, opportunities for exchanging expertise between Swedes and Norwegians in the mining and oil and gas industries have been emphasized in the Kiruna–Narvik border area. (Read more about the Kiruna–Narvik case study in the article by Bjarge Schwenke Fors.) Cross-border cooperation can also be a way of generating critical mass, e.g. by agreeing upon common welfare service solutions or creating cross-border clusters of companies and research institutions in order to enhance innovation activities. Furthermore, through the joint management of programmes and projects, cross-border co-operation enhances organizational and policy learning, while contributing to the removal of border obstacles, thereby improving the living conditions for people within a cross-border region.

Moreover, the added value of cross-border co-operation can lie in building structures for further co-operation and ultimately in enhancing cohesion. It can be both the building of institutional capacity across borders and a focus on physical infrastructure. The current ETC programmes building on existing cross-border co-operation are an example of the former; an example of the latter is the Öresund Bridge, which created better conditions for co-operation and exchange in the Sweden—Denmark cross-border region.

In some Nordic country borderlands, as well as in other parts of Europe, strong cross-border structures and close collaboration across borders have been established to solve common problems. The question of what value cross-border and transnational co-operation can add to regional and local development will guide the current (2014 – 2020) ETC programme period.

The Territorial Agenda of the EU is an informal strategic transnational policy paper that refers to territorial cohesion in Europe. The Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020 (TA 2020) is the updated strategy jointly approved by the ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development. It was approved under the Hungarian Presidency on 10 May 2011. The Territorial Agenda highlights the need and potential for a territorial perspective on strategic transnational policy-making. It calls for specific attention to be paid to external EU borders, better policy co-ordination across countries in supporting cross-border and transnational functional regions, and ensuring that European Territorial Co-operation programmes are better embedded within national, regional and local development strategies by promoting the use of local assets for ensuring global competitiveness of the regions.

Interreg (officially European Territorial Co-operation, ETC) is financed under the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and is part of the structural and investment policy of the EU. Interreg was introduced as one of the objectives of EU Cohesion Policy in 2000. One of the main targets of the Interreg initiative is to support equal economic, social and cultural development of the whole territory of the EU, by fostering cross-border, transnational and interregional co-operation. The fifth programming period of Interreg started in 2014 and will run until 2020.

This article is part of Nordregio News #1. 2015, read the entire issue here.