This article summarises findings from two Nordregio projects – Polar Peoples, which examines aspects of population change in the Arctic, and Nunataryuk, which studies the impact of permafrost thaw.

The Arctic regions differ considerably in terms of population size, growth rates and the structure of settlements, as well as fertility, epidemiological and migration patterns. There are also significant demographic differences between indigenous and non-indigenous populations in the Arctic. Across the Arctic, there has been a general trend towards the concentration of populations into larger urban centres and a decline in smaller settlements.

In the North American Arctic, Alaska and the three northern territories of Canada have had significant population growth over recent decades and, in the North Atlantic, the population of Iceland has also grown significantly. The populations of Greenland and the Faroe Islands, on the other hand, have changed very little. In all Norwegian Arctic regions, the population has grown, while there has been moderate overall growth in Swedish and Finnish Arctic regions, despite a decline in some of them. The population of the Russian Arctic has continued its post-Soviet contraction with ongoing decline in all but two regions. Population change for any country or region consists of two components: natural change, which is the difference between the number of births and deaths; and net migration, the difference between people migrating to a region and those leaving.

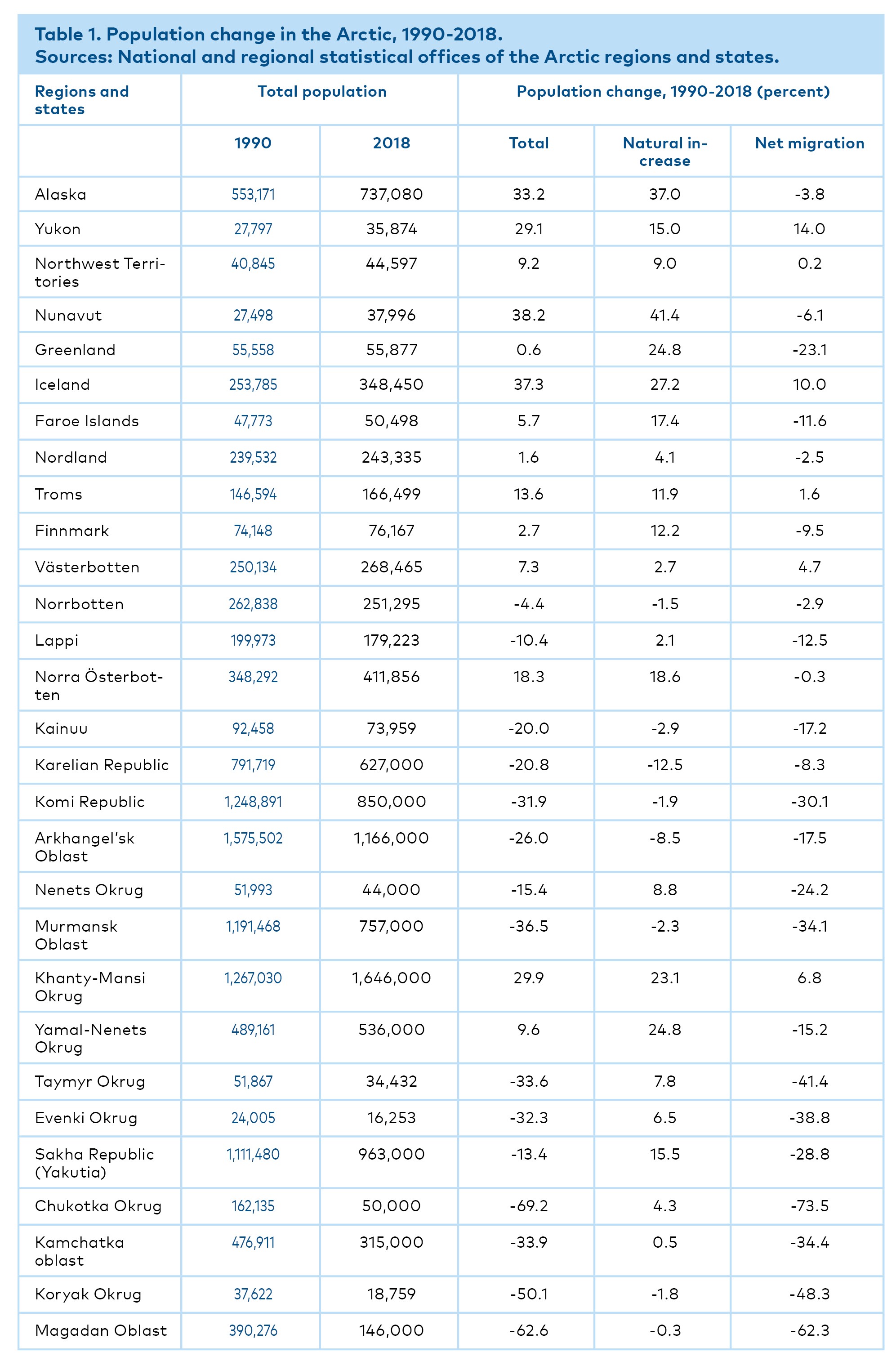

Arctic population change at regional level

Since 1990, the population of Alaska has grown by one-third thanks to a large natural increase and only moderate outmigration (Table 1). The populations of the three Canadian northern territories have continued to grow. Since 2001, the population of the Northwest Territories (NWT) has grown by 9%, mostly from natural increase as net migration was close to zero. The population of the Yukon increased by 29% between 1991 and 2016, through roughly equal contributions of natural increase and net migration. Of the three, Nunavut showed the highest growth at 41% since 2000; there has been some outmigration, so the growth was due to natural increase from higher fertility and the younger age profile of the predominantly Inuit population.

The population of Iceland has grown considerably – by 38% – since 1990. In recent years, migration has made a significant contribution to population growth; like other Arctic regions, migration in Iceland fluctuates considerably, but in Iceland’s case some of the reasons for this are unique to it. In 2013, net migration moved into positive numbers, and it has increased every year since then.

The population of Greenland has remained remarkably constant over time at 56,000, varying by less than 1,000 each way. This is because any increase in births is balanced by net outmigration. Because its population is largely indigenous, Greenland has a younger age profile and higher fertility rates. The Faroe Islands has had moderate population growth of 5.7% since 1990 and a similar pattern of natural increase to Greenland, almost offset by net outmigration.

Since 1990, the population of Norway has increased by 25%. The populations of the three Arctic regions have also increased but much more slowly: Nordland by 1.6%, Troms by 13.6% cent and Finnmark by 2.7%.

The population of Sweden has grown significantly since 1990, by 19%, of which one-quarter was from natural increase and three-quarters from net immigration. The population of Västerbotten has grown much slower than the national rate, by 7.3% since 1990. The population of Norrbotten has declined by 4.4% since 1990.

Since 1990, the population of Finland has increased by 11%. Since then, the contributions of natural increase and net immigration have been roughly equal. Of the three Arctic regions, only Pohjois-Pohjanmaa (Northern Ostrobothnia) grew during this period, by 18%, which was entirely due to natural increase. The population in Kainuu declined by 19% and in Lappi by 10%. In both cases, nearly all the decline was attributable to outmigration.

Russia’s cities are much larger than those in other Arctic regions as a result of the Soviet Union’s central planning system. The break-up of the Soviet Union, the transition to a market economy and the liberalisation of society resulted in significant demographic upheaval in Russia and the Russian north. The population of the Russian north adjusted to the new economic conditions by declining by 20% through the large-scale outmigration of nearly a quarter of the population and many settlements across the Russian Arctic were closed or abandoned when they became depopulated. The largest population decline was in the Far East, where the population of Kamchatka declined by one-third, the Magadan oblast by nearly two-thirds and the Chukotka okrug by nearly 70%.

Arctic population change at settlement level

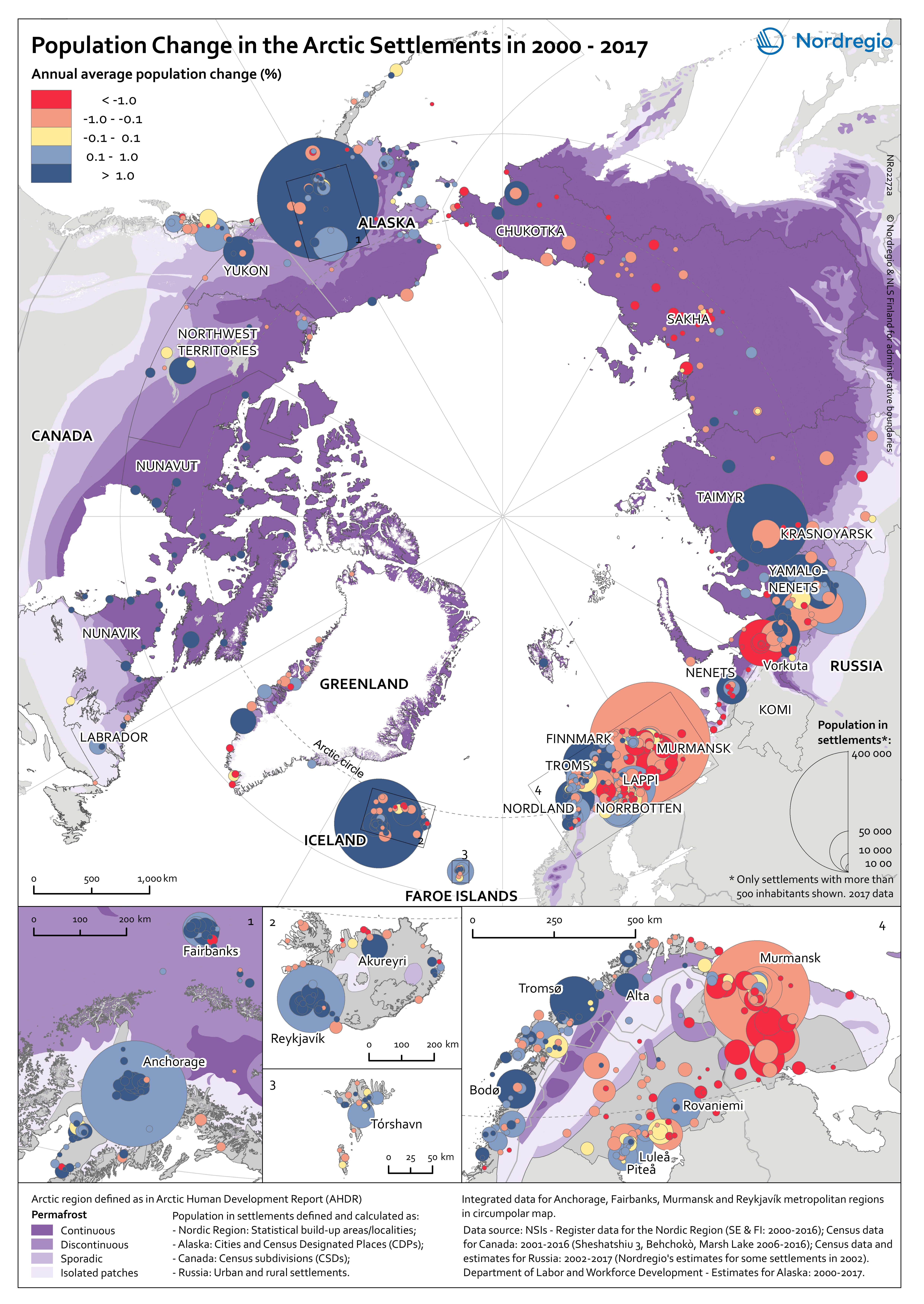

As part of the Nunataryuk project, Nordregio is compiling a socio-economic atlas of population centres in the Arctic to measure the impact of thawing permafrost. Figure 1 provides an overview of population change for settlements with 500 inhabitants or more during the period 2000 to 2017. The layer below this shows the extent of permafrost across the Arctic. Four zoomed-in maps show Arctic Fennoscandia, Iceland, Faroe Islands and Alaska, where settlement density is high.

In Alaska, the population decline in smaller settlements located far from the two populous cities, Anchorage and Fairbanks, has been caused by outmigration, which has cancelled out positive natural population growth.

In Canada’s three northern territories, where there are large tracts of uninhabited land, most people live in a limited number of settlements; in Yukon there are 25 settlements and 70% of the population lives in the largest, Whitehorse. In NWT there are 33 communities, and 48% of the population lives in the capital, Yellowknife. Nunavut, which has 25 communities, has a deliberate policy of moving public-sector jobs out to smaller communities outside the capital of Iqaluit, where only 21% of the population lives.

The Greenlandic population of 55,877 (at 1 January 2018) lives in 89 localities including 17 towns, 54 settlements, five farms, and five stations. Nearly one-third of the population lives in the capital, Nuuk.

In the Faroe Islands, about 40% of the population resides in the capital of Torshavn and the remainder in a number of smaller coastal settlements on the 16 (of 18) inhabited islands. The government has long had a policy of linking all settlements via the national road system through a series of bridges and undersea tunnels in an effort to connect the whole population and reduce decline in remote villages.

The Arctic regions of Norway, Sweden and Finland have more diversified economies and larger populations. Most of the smaller settlements in Arctic Fennoscandia have witnessed population decline between 2000 and 2017, with northern Norway the exception to this. The dominant pattern in Fennoscandia is population growth in larger settlements and population decline in surrounding smaller settlements. This is similar to the pattern observed in the North Atlantic – Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands. New inhabitants have been arriving in the capitals (Reykjavik, Nuuk and Torshavn) and regional centres, from both domestic and international locations, while settlements in sparsely populated areas are becoming less attractive to incomers.

In post-Soviet Russia, the northern region can be divided into the oil and gas areas of the Khanty-Mansi and Yamal-Nenets okrugs, and other areas. The population is growing in the oil and gas areas and declining slowly in the others. Over 75% of analysed settlements have been shrinking throughout the 21st century, mainly as a result of outmigration.