The path to a carbon neutral Nordic region runs through our innovative industry, our forests and our homes. It travels by car, boat and train (it bikes and walks too). And it needs to be aided by better, more integrated policy support

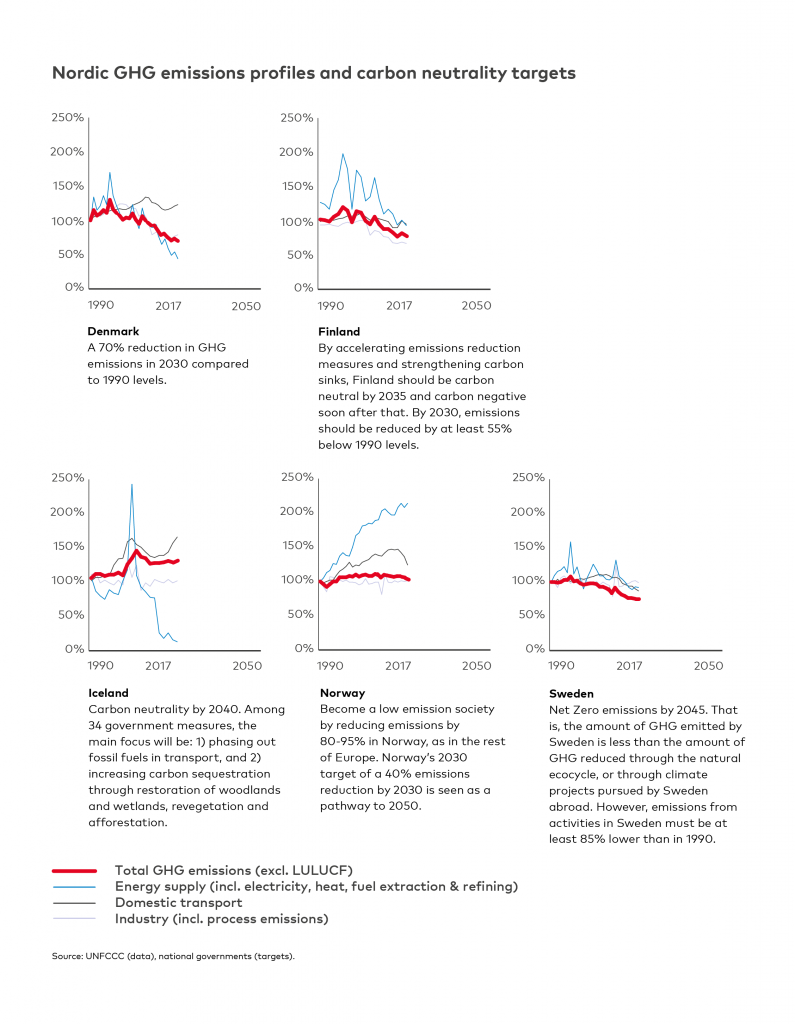

Each of the Nordic countries, together with a majority of EU member states, have voiced policy commitments to achieving carbon neutrality within the next three decades. Finland’s target is to be carbon neutral by 2035, and it’s supported by the most ambitious climate programme in the world. Hopefully, it will lead to Finland being the first fossil-free society in the world.

In the spirit of collaboration, each of the Nordic countries has set climate targets that they claim will lead to carbon neutrality. The Nordic Prime Ministers also signed Declaration on Carbon Neutrality in January 2019. This reiterates their support for a European carbon neutrality target and states that the Nordic countries will ramp up climate action by 2020. Alongside politicians, the CEO’s of some of the largest Nordic companies have pledged their support for carbon neutrality and have committed to increased public-private collaboration.

Carbon neutrality describes a transition path that will help us achieve the 1.5-degree target set by the Paris Agreement. It is achieved when the emissions we produce are in equilibrium with our ability to absorb or sequester them. Absorption takes place via the natural environment, including the vast forests of the Nordic Region. Sequestration refers to innovative solutions such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and direct air capture (DAC) that have the ability to contain emissions before they reach the atmosphere or remove emissions already polluting the air.

However, carbon neutrality is only a step on the path to sustaining the 1.5-degree target. A tweet by Glen Peters, Research Director of the Center for International Climate Research in Norway, highlights that we will need negative CO2 emissions after 2050 in order to limit climate change to 1.5 degrees from pre-industrial levels.

All climate mitigation scenarios (e.g. the International Energy Agency and the IPCC) include carbon storage as a crucial means of achieving 1.5-degree target. However, this doesn’t mean that we can depend on a cocktail of carbon capture innovations to solve our emissions problems. Negative CO2, a flagship project of Nordic Energy Research focusing specifically on the potentials of CCS technologies, specifically highlights this:

“CO2 emissions must be reduced drastically now, not just from energy, but also transport, industry and agriculture. The requirement for technologies that remove CO2 from the atmosphere at some scale is non-optional, but negative emissions will never be a safety net for reduced or delayed climate action now.”

Negative CO2 Project, supported by Nordic Energy Research

This insight promotes the systems view that’s needed to achieve carbon neutrality. It’s a no-stone-left-unturned perspective. It highlights a Nordic energy system that’s full of important trade-offs. It’s through these trade-offs that a view emerges about how green buildings can play an important role towards achieving Nordic carbon neutrality.

Energy efficiency in buildings – saving forests and powering cars

There is a (seemingly) logical claim where Nordic success in developing renewable electricity and heating means that climate efforts should focus less on buildings and more on the difficult challenges in the transport and industrial sectors. However, a holistic view where energy can be converted, stored and transmitted in increasingly flexible ways means that energy saved in buildings can instead be used towards solutions in other areas.

Buildings account for roughly 43% of energy consumed in the Nordic Region and space-heating accounts for 60% of that total. Due to longer winters and larger living areas per person we use 30% more energy in buildings compared to the rest of Europe. Yet the corresponding CO2 emissions are 50% lower than the EU average, due to a larger share of renewable energy use, especially form biomass. As shown below, a carbon-neutral Nordic scenario includes biomass and waste as the primary energy inputs for heating until at least 2045.

However, increased energy efficiency brought about by aggressive standards for new buildings and comprehensive strategies to retrofit existing buildings can free-up biomass for at least two critical uses. First, it will take pressure off of planned forest exploitation, adding an essential layer of resilience to sustainable forest management. Based on UNFCCC data, Nordic forests annually absorb 32% of the total greenhouse gas emissions we produce. Reducing the pressure on this valuable resource will not support the role of Nordic forests as a carbon sink, but it will also help to promote biodiversity and many other environmental benefits.

The biomass saved through the development of a green building stock could instead be used as an input for fuel in the transport sector – a sector which faces the most significant challenge to decarbonise in the coming decades. The figure below shows that renewables in transport more than doubled between 2011 and 2016, and over 80% of this increase has been due to consumption of biofuels. If innovation can lead to financially viable production of bio-fuel from forest products, this has the potential to compliment electric-mobility solutions by enabling significant carbon reductions in aviation, maritime transport and road freight.

The future is today for green building

Unlike the transport, energy and industrial sectors, scalable and economically-viable low-carbon solutions already exist for buildings. The challenge isn’t constructing new green buildings – those are already regulated by high energy efficiency standards – it’s greening the inefficient buildings that are already built. One report suggests that 85% of buildings throughout Europe will still be in use in 2050, and 97% of these will have to be renovated to achieve Europe’s energy efficiency goals. This would require a rate of retrofitting that is almost 250% higher than today, and the Nordic Region is no exception to this trend.

Green building isn’t limited by a technology or innovation gap; the challenge is increasing awareness and investment among building owners, ranging from municipalities, private housing companies, housing associations and individual homeowners. The high upfront investment costs, coupled with the 10-15 year payback period for energy retrofits, creates a challenging environment for triggering the scale of investment that’s needed.

The combination of available solutions and pressure for immediate action should inspire policy and financial frameworks to support green retrofits. Unfortunately, the Nordic countries fall well short of being a European leader. In Sweden, there is a distinct lack of grant-based schemes or financial instruments supporting private investment. The same holds true for each of the Nordic countries.

The building requires some incremental policy innovation. Financial instruments that are supported by public funds have already proven to be successful elsewhere in Europe, and they provide a great opportunity to leverage public funds to trigger large-scale private investment. This can lead to a robust funding framework whereby all building owners could have access to interest-free loans that can be repaid with money saved on monthly energy costs.

While the Nordic Region leads the way towards carbon neutrality in many regards, the building sector offers the chance to look to others for inspiration. New policy instruments need to be created by Nordic governments, together with support from financial institutions, energy agencies, and construction firms. Our forests and transport needs may just depend on it.

This article provides a preview to a thematic chapter on pathways to the Nordic carbon Neutrality, which will appear in the upcoming State of the Nordic Region 2020 report by Nordregio. Nordregio is also the lead partner of the INTERREG Europe project Social Green – Regional Policies towards Greening the Social Housing Sector