The population of the Nordic Region continued to grow in 2022 but only due to high immigration as the number of deaths exceeded the number of births.

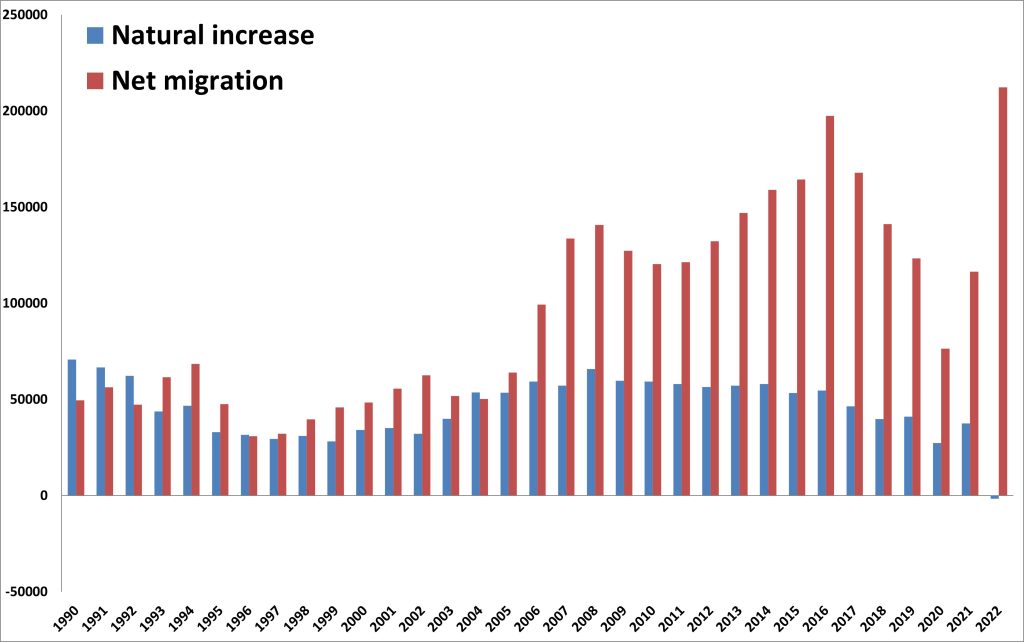

In 2022, the number of births was the smallest in the previous three decades and the number of deaths was the largest. The number of persons migrating to the region was the largest over this period (see figure 1). At this time, it is difficult to disentangle the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on fertility, mortality, and migration and the effects might be temporary.

However, if the trends of low fertility and high immigration persist, they could have a profound impact on the populations and societies in the Nordic Region.

The population of a country or region changes through a combination of births, deaths, in-migrants, and out-migrants. The difference between the number of births and deaths is termed natural increase (which can be negative if the number of deaths exceeds the number of births). The difference between the number of people migrating to an area (referred to as immigrants in the case of international migration) and out-migrants (termed emigrants when migration is out of a country) is called net migration and can also be negative when the number of persons leaving a country or region exceeds the number moving to a country or region.

Population change in the Nordic Region

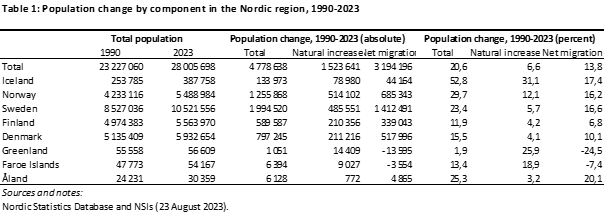

In recent decades, population change in the Nordic Region has been characterized by steady but below replacement-level fertility, steadily rising life expectancy, and high levels of immigration. This has led to population increase through a combined of positive natural increase and net immigration, with the latter accounting for two-thirds of the population increase since 1990 (see table 1).

The population of the Nordic Region has increased by 21 percent since 1990, from 23.2 million to 28.0 million at the beginning of 2023. Iceland grew the most over this period, by more than 50 percent. In 2022, the population increase for Iceland was the largest in any year as far back as population figures go. Norway, Sweden, and Åland grew by between 25 and 30 percent. Denmark, the Faroes, and Finland increased by between 12 and 15 percent. The population of Greenland remained almost the same only increasing by 2 percent.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are different on each component of population change – births, deaths, immigration, and emigration. The impacts differ in severity and timing, with some being temporary reverting to pre-pandemic levels quickly, while others might be more long-lasting indicating a shift to new levels. More time, data, and analysis of these demographic trends are necessary to assess whether they are temporary or if they represent a transition to a new demographic realty in the Nordic Region.

Fertility reaches new lows

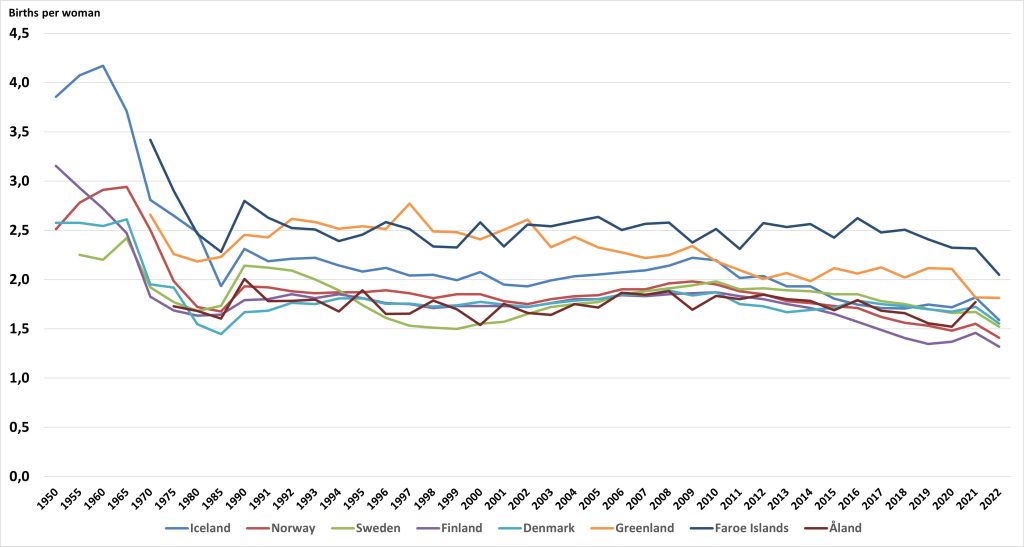

A trend in the Nordic region which is puzzling demographers are the low and falling fertility rates (the number of children a woman would hypothetically have if she passed through her child-bearing years at the current age-specific fertility rates).

The State of the Nordic Region 2020 reported that for Iceland, Norway, and Finland, the current fertility rates were the lowest ever recorded. Since then, the total fertility rates for those three countries have fallen further to new lows, following brief and small increases during the COVID-19 pandemic (figure 2). The fertility rate in Finland was the lowest since monitoring started in the year 1776. The fertility rates for Greenland and the Faroe Islands are also new lows. The rates for Sweden and Denmark also declined in 2022 to near record lows.

With these recent declines in fertility, all Nordic countries and autonomous territories have fertility rates below replacement level, of about 2.1 children per woman. The fertility rates for the five Nordic countries range from 1.59 children per woman in Iceland to 1.32 in Finland. For the three autonomous regions, the rates range from 2.05 in the Faroes to 1.77 in Åland (based on 2021 data).

These declines might not affect cohort fertility – the number of children women ultimately have – as they might be delaying fertility. However, these declines do impact current population change. The number of births in a year is a function of the total fertility rate and the age structure of the population, specifically the number of women of childbearing ages. Following a small increase in the number of births in 2021, partially consisting of babies conceived during the peak of the pandemic, there was a decline in 2022 to the lowest number of births in the past three decades despite the population and number of women in the childbearing ages being larger.

This decline in fertility, combined with a rise in the number of deaths (more below), resulted in their being more deaths than births in the Nordic Region. Finland has had more deaths than births since 2016 due to an aging population and the lowest fertility rate among Nordic countries. In 2022, deaths exceeded births also in Denmark and came close to doing so in the other Nordic countries.

Life expectancy peaks

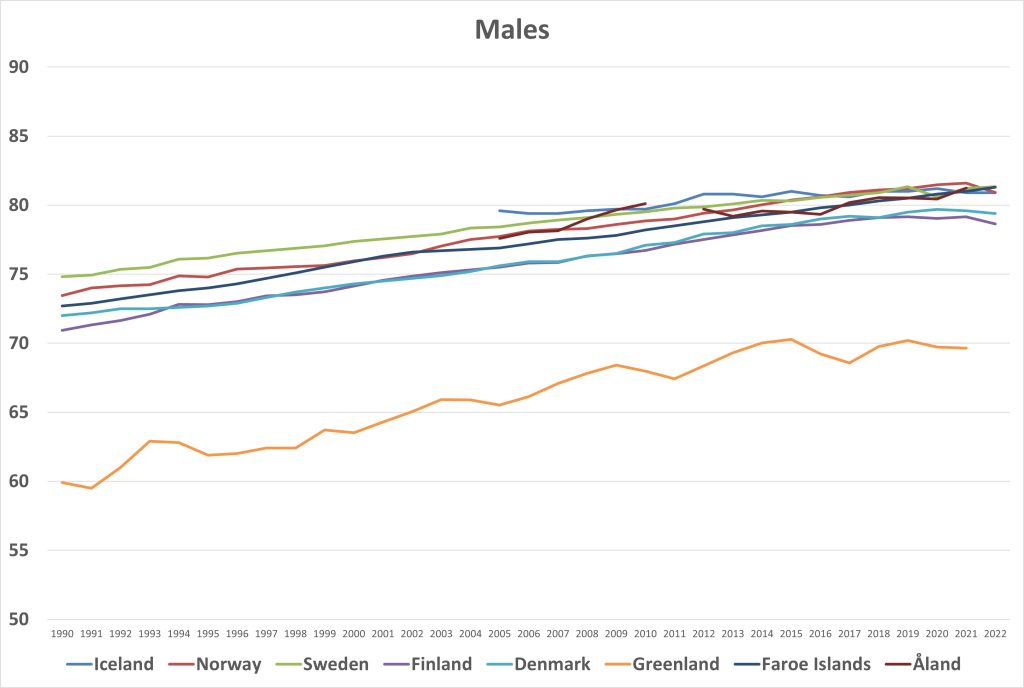

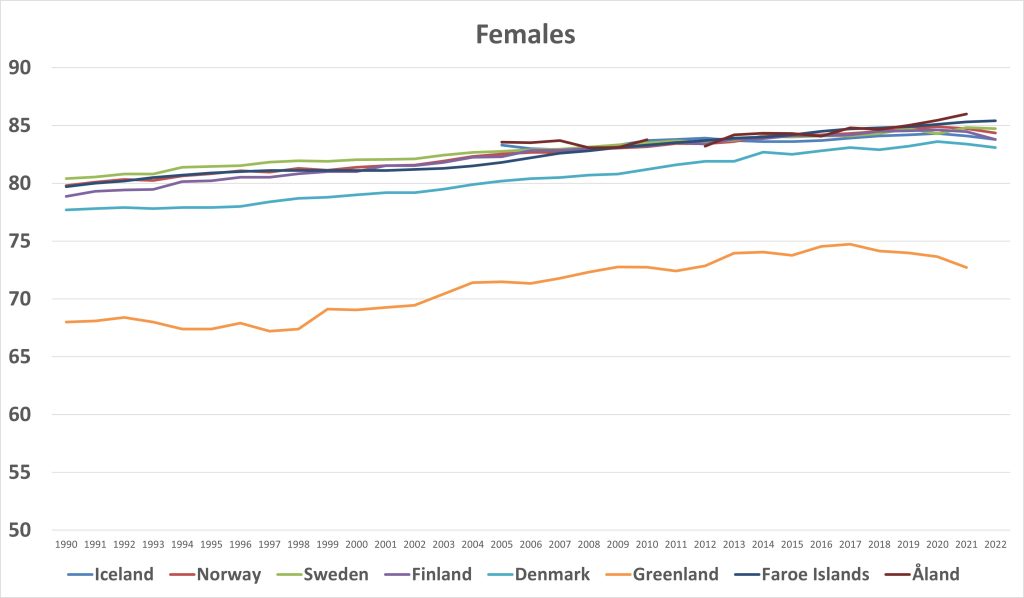

Mortality in the Nordic Region has been characterised by steadily increasing levels of life expectancy. Since 1990, life expectancy for males has increased by an average of 7 years, while female life expectancy has increased by 4 years. The Nordic countries have long had levels of life expectancy which are among the highest in Europe for both males and females.

There is a net effect on morbidity and mortality from the pandemic with increases in deaths due to COVID-19, stress-related causes, increased obesity, alcohol, and drug use, deferred medical treatment, and worsened mental health.

Simultaneously, there are decreases in other causes of morbidity and mortality from people working at home and not contracting contagious diseases, increased sanitation, and fewer road and traffic accidents. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality have yet to have fully played themselves out. There has been considerable speculation in the media and academia as to the short and long-term effects of the pandemic and which countries have fared better or worse than others.

In 2020, the first year of the pandemic, Sweden stood out from the other Nordic countries by having a decrease in life expectancy. However, it was the other Nordic countries which deviated from the rest of Europe where there were almost universal declines in life expectancy. Since then, there have been small declines in life expectancy for both males and females for the Nordic countries other than Sweden.

For males in Iceland and Denmark, highest life expectancy was in 2020 and there have been small declines since then (figure 3). For Norway and Finland, male life expectancy peaked in 2021 before declining. For Swedish males, life expectancy has recovered and is at the same level as it was prior to the pandemic. Among the autonomous territories, life expectancy for males in Greenland peaked in 2015 and has declined slightly since then. For the Faroes and Åland, male life expectancy did not decline during the pandemic and reached its highest level in 2022.

Life expectancy for females showed a similar trend with peak levels for Iceland, Norway, Finland, and Denmark in 2020 and slight declines since then (figure 4). For females in Sweden life expectancy recovered and reached its highest level in 2022. Life expectancy for females in Greenland peaked in 2017 and has declined since then. For females in the Faroes and Åland, life expectancy continued to increase during the pandemic and peaked in 2022.

The recent declines in life expectancy in the Nordic countries have been quite small and might be temporary. They have an insignificant impact on population change. More time and data are needed to understand the causes of these declines and determine if they are a cause for concern or intervention.

Immigration reaches a new high

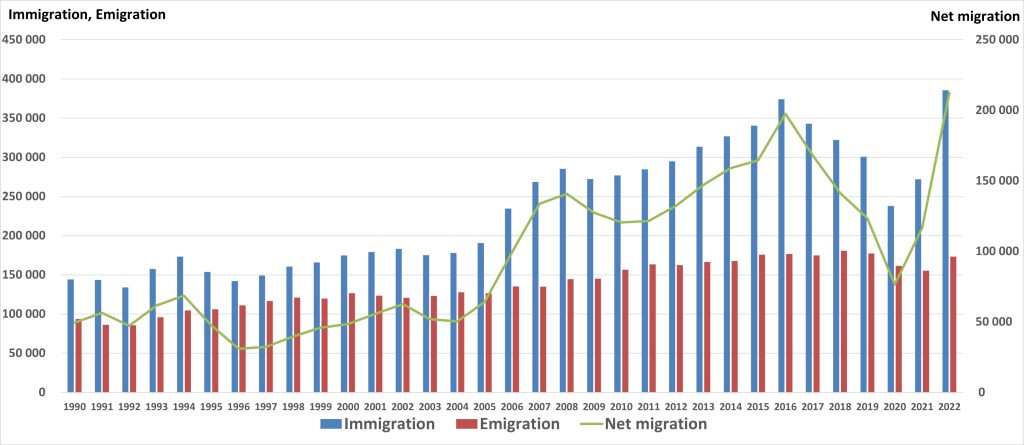

If not for positive migration into the Nordic Region, the population would have declined in 2022. There have been more people migrating to the Nordic Region than away since 1990 and net immigration has accounted for two-thirds of population growth.

Like the component natural increase, which is composed of births and deaths, net migration is composed of two quite different flows of people – those migrating to the Nordic countries and those migrating away from them – and should be analysed separately.

From 1990 to 2004, immigration to the Nordic Region averaged about 160,000 persons a year and there was a positive net migration of about 50,000 annually (figure 5). With the large EU expansion in 2004, both immigration and net migration rose steadily. Immigration peaked in 2016 at 374,000 during the ‘refugee crisis’ when net migration was 197,000. Both then declined reaching lows in 2020 at the start of the pandemic. Both immigration and net migration reached new highs in 2022, when there was an immigration of 385,000 persons and a net migration of 212,000. These are the highest levels since 1990 and likely ever. For Iceland, it is the highest positive net migration ever.

The reasons for the surge of immigration in 2015-2016 when so many people were coming to the Nordic countries as refugees is obvious. This was a unique event which was resolved politically at the EU level, thus leading to a decline in the following years.

The reason for immigration reaching a nadir in 2020, during the pandemic, is also explainable as there were many restrictions on migration and mobility at that time. Some of the upturn in immigration since 2020 could be explained by persons wanting to migrate during the pandemic and delaying their moves. However, other factors could be contributing to the surge in immigration.

The FUME (Future Migration Scenarios for Europe) project modelled global and national migration flows based on relative income levels, diaspora populations, and other factors. Under any scenario Europe is expected to continue to be a major destination for migrants from elsewhere in the world. Within Europe, the countries of northern Europe, which include the Nordic countries, are expected to be major destination countries.

A new demographic reality in the Nordics?

If the trends of low fertility and high immigration persist, taken together they will have a significant impact on the population structures in the Nordic countries. The effects will not be felt immediately as these indicate shifts in population change which will impact population structure only over time.

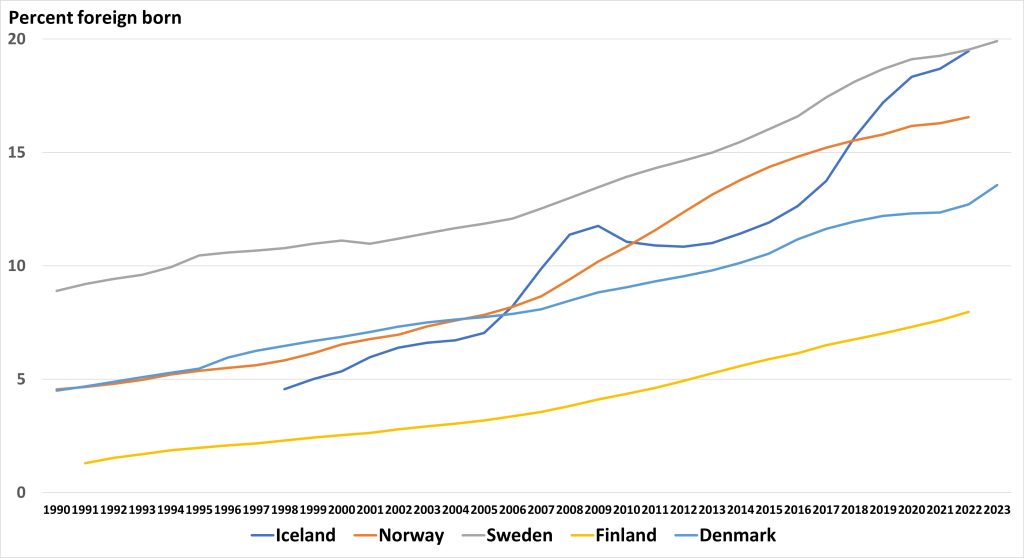

The Nordic welfare model rests, in part, on high levels of employment. If many of the additions to the populations are foreign-born, it could take time to integrate them into the labour force. The recent uptick in immigration is a continuation of a trend which has been underway for decades.

In 1990, in both Norway and Denmark the percent foreign born was 4.5 percent (figure 6). The percent has increased to 17 percent in Norway and 14 percent in Denmark, the latter which has had more restrictive immigration policies. Finland had the smallest share foreign born in 1990, just 1 percent but it has increased to 8 percent.

Among the Nordic countries, Sweden has long had the largest foreign population, but the percent of residents born outside Sweden continued to increase from 9 to 20 percent since 1990. Iceland has had the largest increase in foreigners as the percent foreign born in Iceland has increased 4 percent in 1998 to 20 percent currently. The levels for Sweden and Iceland, where one-in-five residents were born outside those countries, are among the highest in Europe and are higher than traditional migration destination countries such as the United States.

There have been concerns about the aging population in the Nordic countries for some time and the low fertility rates will accelerate this trend. Smaller cohorts now being born will replace large cohorts entering retirement age creating a burden on the pension and health care systems. These demographic trends and their underlying causes will be explored in more detail in the State of the Nordic Region 2024 to be published in mid-2024.