But won’t it burn down? This is usually the first question we get when we talk to people about modern wood construction. There is some truth in the question and to find it we need to go back in history.

Devastating fires in cities like Umeå and Sundsvall in the 1800s led to a ban on wooden buildings taller than two storeys in Sweden, as in many other countries. In the era of modernism that followed, wood was considered a low-quality second-class material to be replaced with ‘good quality’ steel and concrete.

Today, a new revolution has begun, with modern wooden buildings sprouting like mushrooms from apartment blocks to schools, bridges, and the iconic SARA Culture Centre in Skellefteå is a shining example. With participants from the Baltic States, we recently had the opportunity to explore the building as part of a study tour for our BSRWood project that seeks to speed up the development of wood construction in the Baltic Sea Region.

Going on a “Träsafari”

“Skellefteå did not need to burn because we demolished it ourselves” joked the head of the municipal building permit department as we began a tour through SARA. It is an awe-inspiring building complex that combines a conference centre, community spaces, a library and a 20-story high hotel skyscraper. SARA was built using 9,000 m3 of timber harvested from a 120km radius and stores around 6,000 tons of CO2 in the building’s lifetime. For our participants from the Baltic region, it was inspiring to not only see the building but hear about the whole planning and design process, as well as how they solved the technical challenges that brought the project to fruition.

Later we continued with a “Träsafari” (wood safari), a guided tour to several sites in the area including Bonnstan, an old church village from which one may spot Lejonströmsbron, the oldest (1737) wooden bridge in Sweden. A short distance away stands the new pedestrian wood bridge, Älvsbackabron (2011) with a 130-meter span, the longest wooden bridge in the Nordic countries. A final stop was the Morö backe school where we learned about the health benefits of wood and how the visually pleasing material has a positive effect on the learning environment.

Overcoming barriers to wood construction

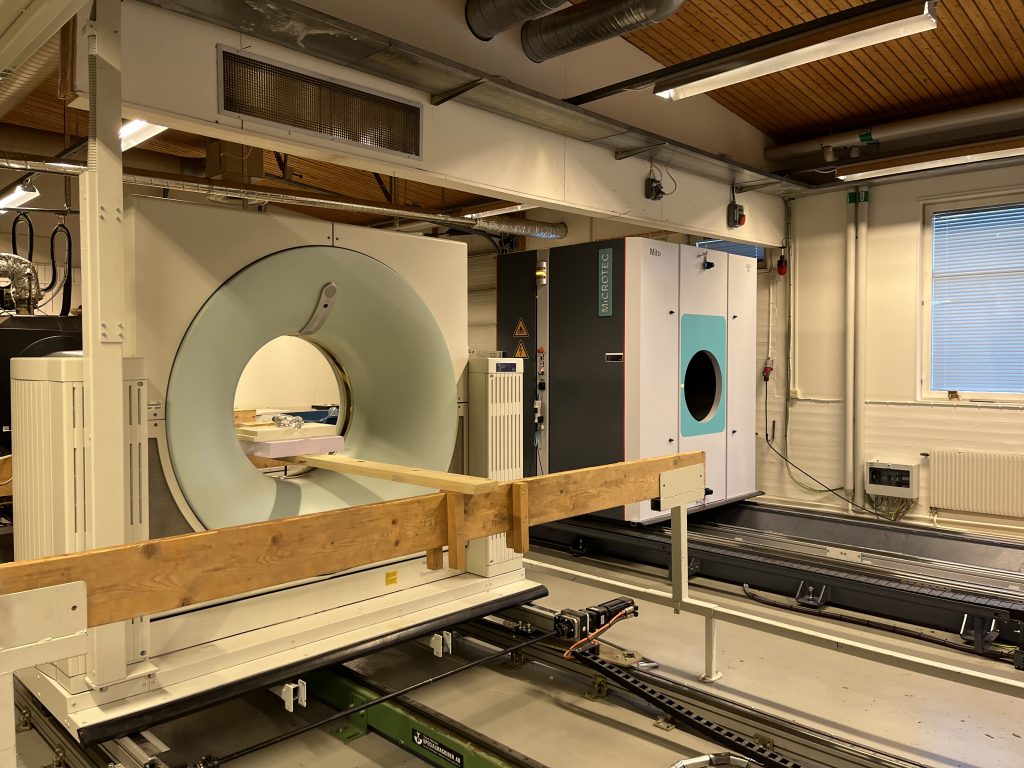

As for the second day, it was devoted to workshops and discussions among our study tour participants, starting with presentations from Luleå Technical University and Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE). They explained their role in driving innovation surrounding wood construction, such as fire safety, sound and energy insolation, structural engineering, etc. We observed their flashy x-ray scanner, used to measure and visualise log properties, and to predict strength and grade of sawn boards. Afterwards, we led a world café workshop on systems of innovation where participants dived into the enabling and hindering factors for the development of wood construction, as well as the role of public institutions, markets, academia in overcoming barriers.

In Sweden, changing legislation has been a fundamental factor in enabling multi-storey building in wood, a process that has been slower in Baltic States. And, in the near future, expected regulations setting limit-values to the climate impact of construction will give a huge boost to the sector. Beyond legislation, sub-national authorities have also played a crucial role in breaking the structural inertia in the construction sector in Sweden through ‘green financing’, coordinating local actors, and generating social awareness.

In spite of the remaining need for research and development, a general conclusion from the discussion was that neither technological innovation nor price are the main barriers to the way forward, but rather structural and cultural issues. Strong structural inertia has resulted from a century-long unchallenged dominance of building systems based on concrete and steel, during which established actors have had very little competition in the market space. The effects of this are visible in a very tangible manner, such as the reluctance of banks and insurance companies to offer more flexible options to consider different building systems or parameters for risk assessment.

Change has nevertheless been possible by creating competing ecosystems, introducing new players, business models, and finance structures, as well as massive efforts made in knowledge creation and sharing. Societal perceptions such as myths about the quality, safety or status of wood buildings, constitute another key challenge. Therefore, much work remains to be done to popularise wood and generate awareness. And yeah, it may burn after all, but just like any other building made of concrete. What is most important is that the people inside can safely escape the fire rather than the building be saved, and these practical questions are solved with adequate fire-safety measures.

Timber innovation

The day after the formal event we drove for an hour through secondary roads in a winter wonderland to visit Martinsons (now Holmen), the pioneering Swedish company producing Mass Timber products, and indeed the first in the Nordic countries to build a factory of Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) boards in 2001. CLT is a structural material used to make walls, roofs, and slabs, which in combination with Glued Laminated Timber (Glulam) is used to make columns and beams that can completely replace concrete and steel to build even skyscrapers.

After the tour of the factory and enjoying a hearty taco Friday at Martinsons’ staff canteen, we asked whether it would be possible to order a small sauna-stuga for Nordregio’s backyard. ‘Impossible!’, their sales manager answered, shaking his head with an apologetic smile. ‘We have orders from Swedish municipalities asking for wooden schools and kindergartens up until the summer, not to mention that Skellefteå is nowhere near finished…”

Find the whole story and results from the trip here.