54 Maps

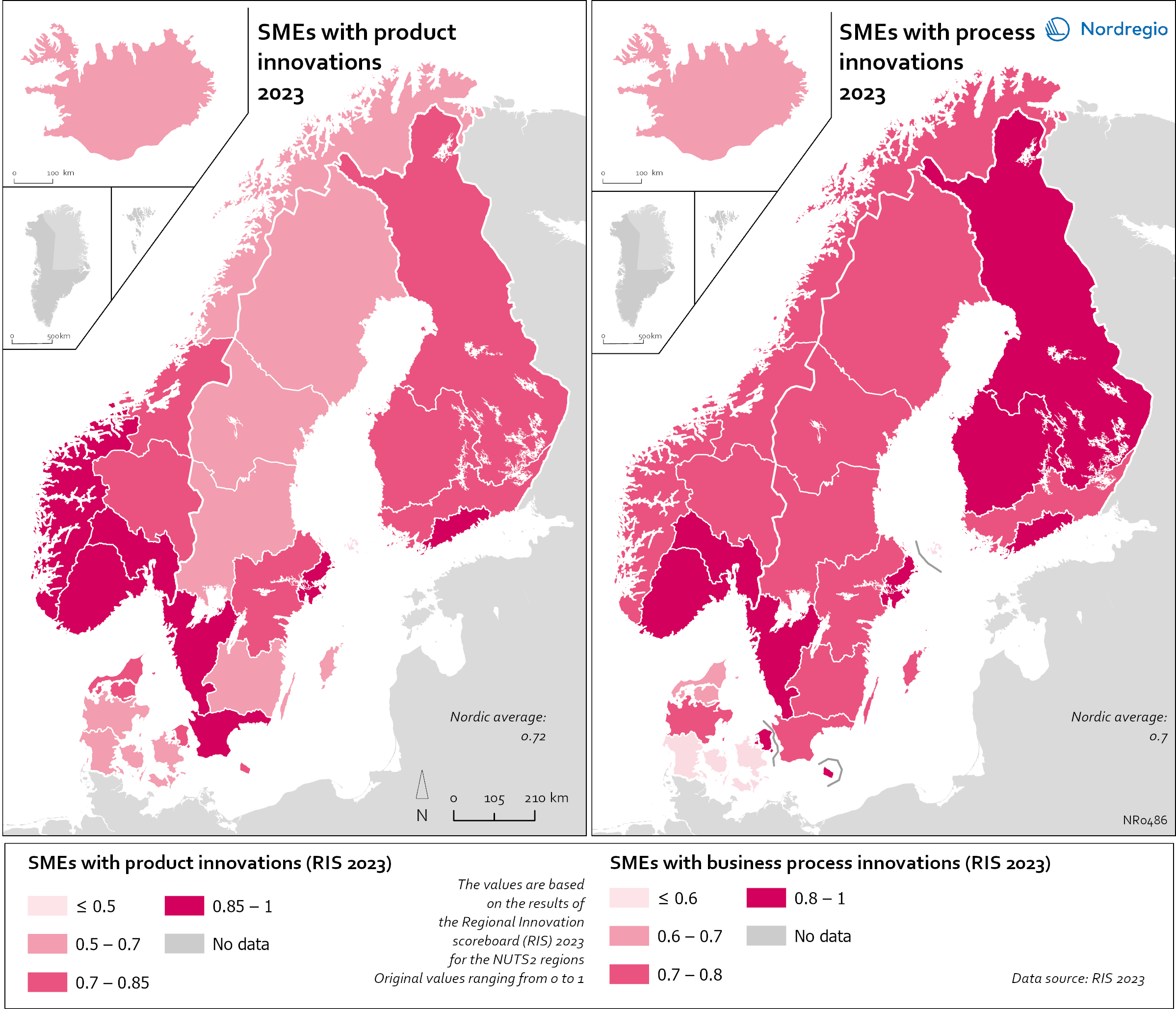

Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) with product and business process innovation in 2023

These maps depicts Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) with product innovation (left map) and process innovation (right map) in 2023. The data is displayed at the NUTS2 level and the data comes from the Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023. The left map depicts SMEs introducing product innovations as a percentage of SMEs in the Nordic regions, calculated as the share of SMEs who introduced at least one product innovation. The values for the map are normalised from 0–10. In this context, a product innovation is defined as the market introduction of a good or service that is new or significantly improved with respect to its capabilities, user-friendliness, components, or sub-systems. Rural regions tend to have lower levels of SMEs with product innovations, while urban regions have the highest levels. In 2023, Åland (0.235) had the lowest number of SMEs with product innovations in the Nordic Region, while Oslo had the highest (1.0). Etelä-Suomi and Stockholm regions were slightly behind, with 0.954 and 0.948, respectively. In Denmark, the leading regions were the Capital Region (Hovedstaden) and Northern Jutland (Nordjylland), with 0.719 and 0.715, respectively. Southern Denmark (Syddanmark) had the lowest level in Denmark, at 0.545. In Norway, the lowest value was in Northern Norway (Nord-Norge), 0.67, while in Sweden it was Middle Norrland (Mellersta Norrland), with 0.53. Taken as an average across the Nordic countries, Norway has a significantly higher number of SMEs with product innovations than the other countries. The right map shows the share of SMEs introducing at least one business-process innovation, which includes process, marketing, and organisational innovations. In general, Nordic SMEs are more likely to innovate in products rather than processes. The highest shares of process-innovating SMEs are found in most of the Finnish regions ranging from 0,79 in Länsi-Suomi to 0,91 in Etelä-Suomi, except of Åland…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

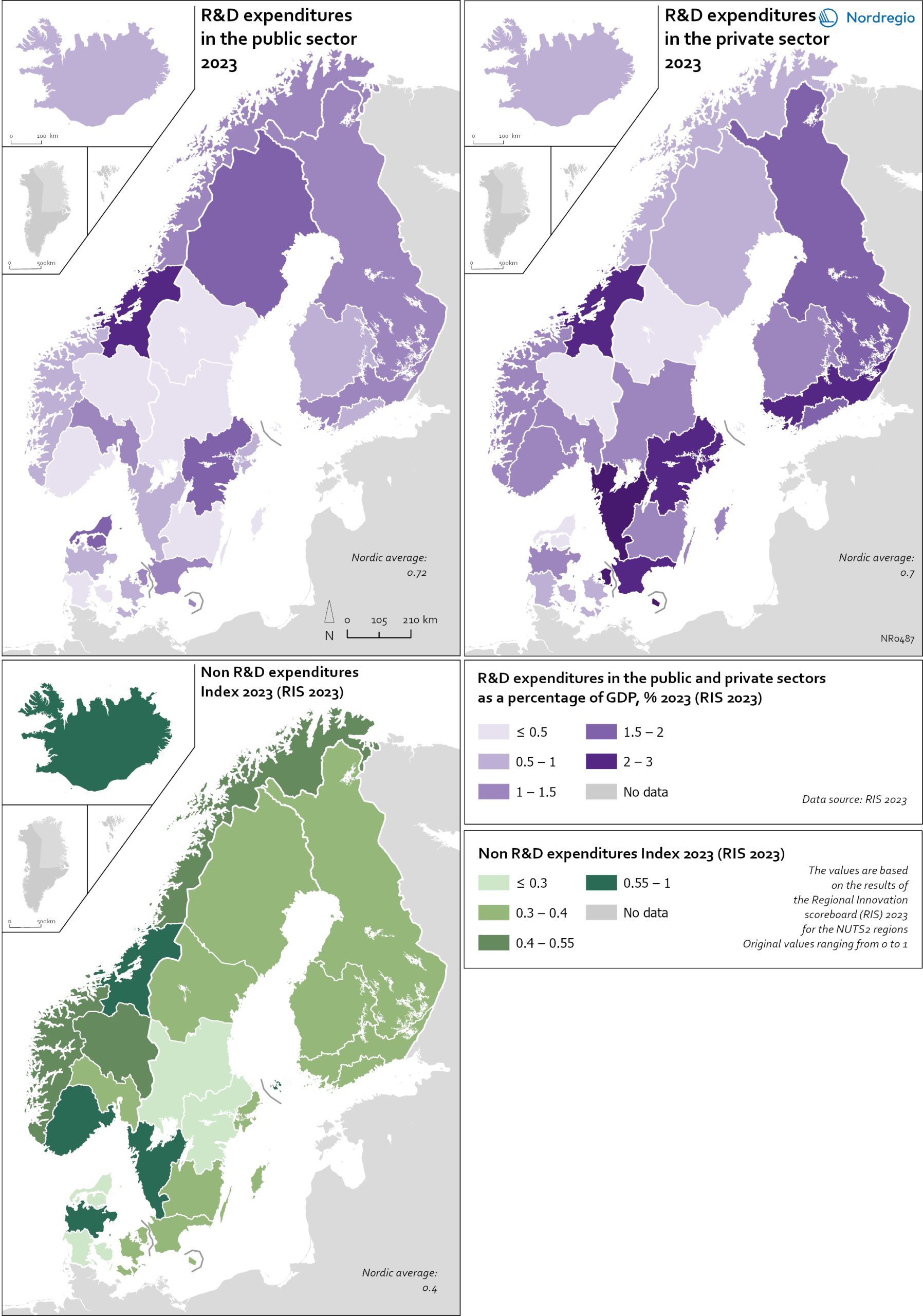

R&D and non-R&D expenditures in the public and private sector

These maps shows the expenditure on Research and Development (R&D) in the public and business sectors as a percentage of regional GDP, along with non-R&D innovation expenditure in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as a percentage of turnover. Together, these metrics offer a comprehensive understanding of the innovation landscape and provide insights into governments’ and higher education institutions’ commitment to foundational research, as well as the competitiveness and dynamism of the business environment and SMEs’ innovation capacity. By considering investment in both R&D and non-R&D activities, these indicators illustrate a broad spectrum of innovation drivers, from basic research to market-driven initiatives, and underscore the diverse pathways through which innovation fosters economic growth and social progress First, the top left map showcases R&D expenditure in the public sector as a percentage of GDP in the Nordic countries in 2023. In that year, the European level of R&D expenditure in the public sector, as a percentage of GDP, was 0.78%. By comparison, the Nordic average was 0.9%. While the more urban regions, in general, lead the Nordic regions, this is not always the case, as shown by the variation between the frontrunners. The leading region is Trøndelag (including Norway’s third-largest city, Trondheim), with 2.30% of regional GDP. It is in third place in the EU as a whole. The next regions are Övre Norrland with 1.77%, Northern Jutland with 1.54%, Östra Mellansverige with 1.52%, and Hovedstaden with 1.49%. A common feature of most of the top-ranking regions is that they host universities and other higher education institutions known for innovation practices. Most Nordic regions have not seen significant increases or decreases in public R&D spending between 2016 and 2023. The top right map focuses on the private sector’s investment in research and development activities and depicts R&D expenditure in the business sector…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

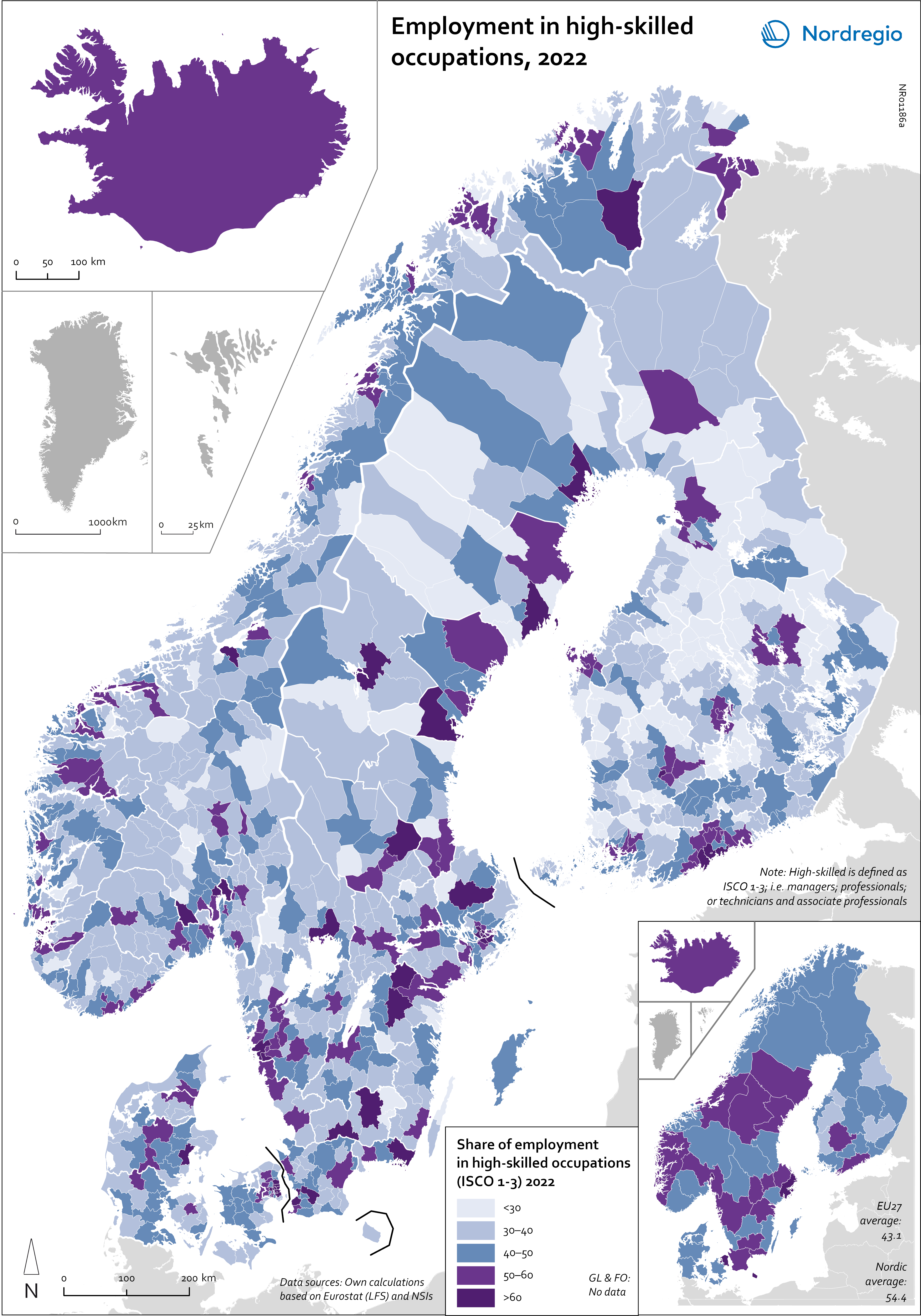

Employment in high-skilled occupations 2022

This map displays the share of high-skilled workers as a share of the total number of workers in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map). “High-skilled workers” is here defined as group 1-3 (Managers, Professionals and Techinicians/associated professionals) of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). For Iceland national data is used. The EU average of high-skilled workers is 43%, and the Nordic countries are at the top of the rankings – 49.5% in Finland, 51.1% in Denmark, 54.2% in Norway, 54.5% in Iceland and 58.9% in Sweden. On a regional level, the highest share is in the capitals and bigger cities, such as Stockholm (72%), Oslo (71%), Hovedstaden (Copenhagen) (60%), Uppsala (60%) and Uusima (Helsinki) (59%). The lowest shares are in the Finnish regions of EteläPohjanmaa, Keski-Pohjanmaa, Satakunta and Etelä-Savo (less than 40%). However, this does not necessarily mean that employers will have a greater chance of successfully recruiting high-skilled workers in the future, partly because those in this group already have jobs and partly due to generally lower investments in education.

2025 April

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

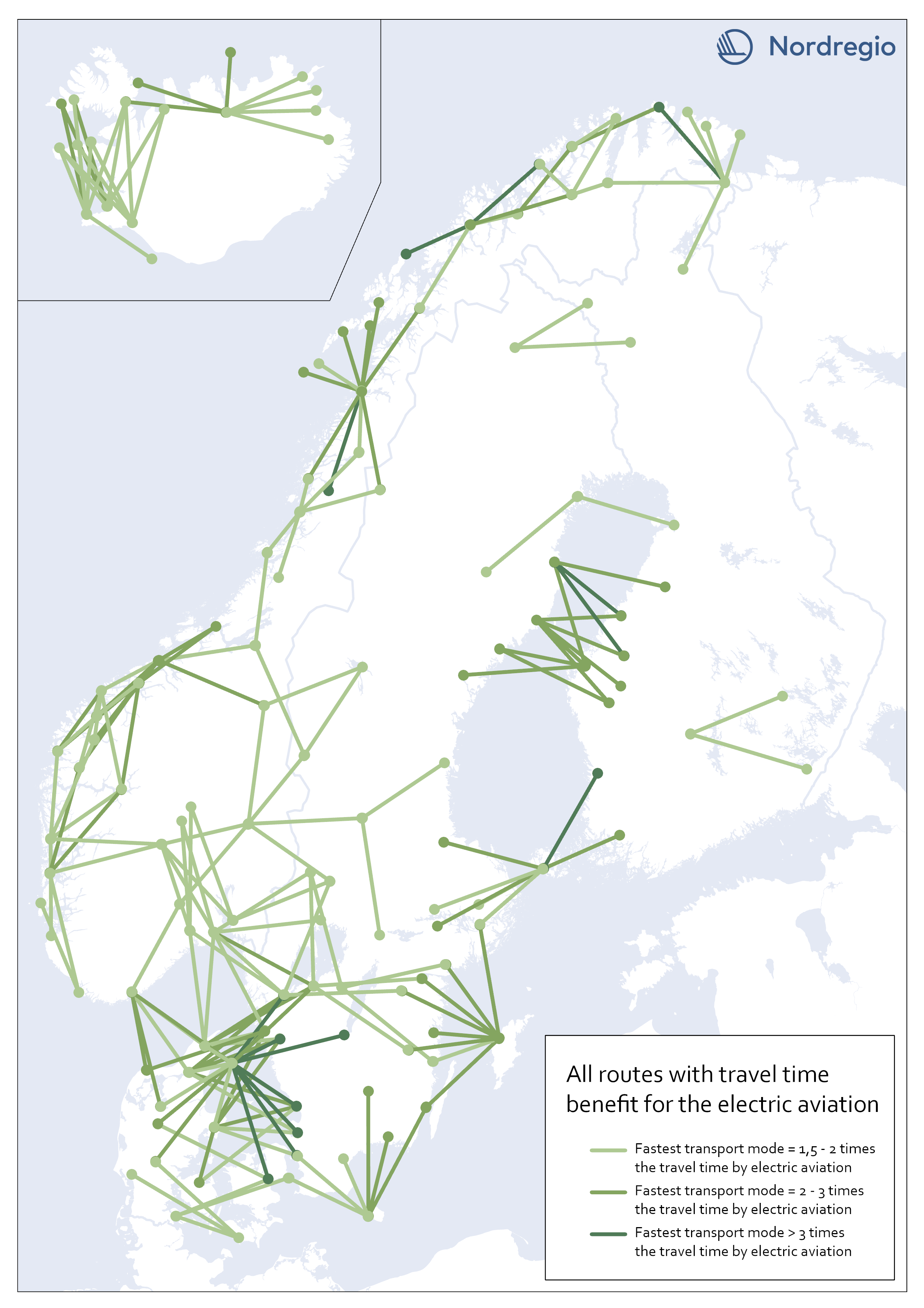

All routes with time benefit for electric aviation

The map shows all routes in our sample with significant travel time benefit for electric aviation. They are 203 in total. A route has a significant travel time benefit if the travel time for both car and public transportation exceeded 1,5 times the travel time for electric aviation. I.e., if one of the existing transport modes is faster or up to 1,5 times the travel time for electric aviation, electric aviation does not have the potential to improve accessibility between the two destinations, according to our analysis.

2023 February

- Nordic Region

- Transport

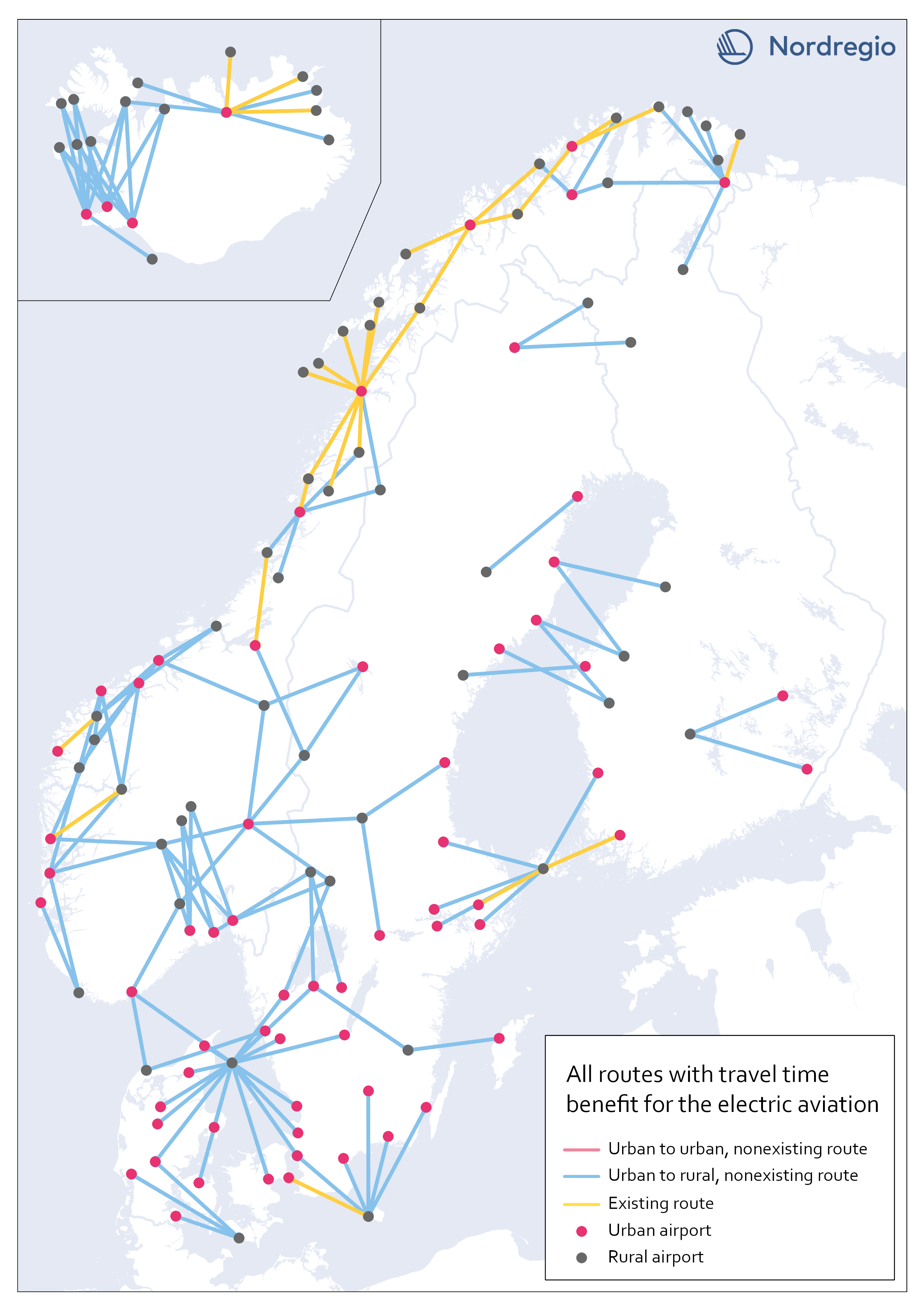

Electric aviation time benefits between urban and rural areas

The map shows all routes between urban and rural areas where electric aviation has significant time benefits compared to other traffic modes. Yellow lines are already served by aviation, while blue color indicates non-existent routes where electric flight would reduce the travel time between destinations. Our motivation for focusing on urban-rural routes was based on the assumption that electric aviation can increase the access for rural areas to public facilities and job opportunities, as well as the possibility of connecting remote areas with national and international transport systems. The result, though, can only be understood in terms of travel time benefits between the areas, and thus reveals little about accessibility to mentioned opportunities. The following are examples of themes to be investigated further within the main project. Identify regional hubs Among others, the project FAIR (2022) has addressed the need to update the flight system to a more flexible aviation network, that meet travelers’ needs with smart mobility. This can be done by identifying demands and establishing regional hubs for electric aviation, which can serve remote and regional areas. The potential of Hamar and Bodö in Norway as regional hubs should be studied more closely.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

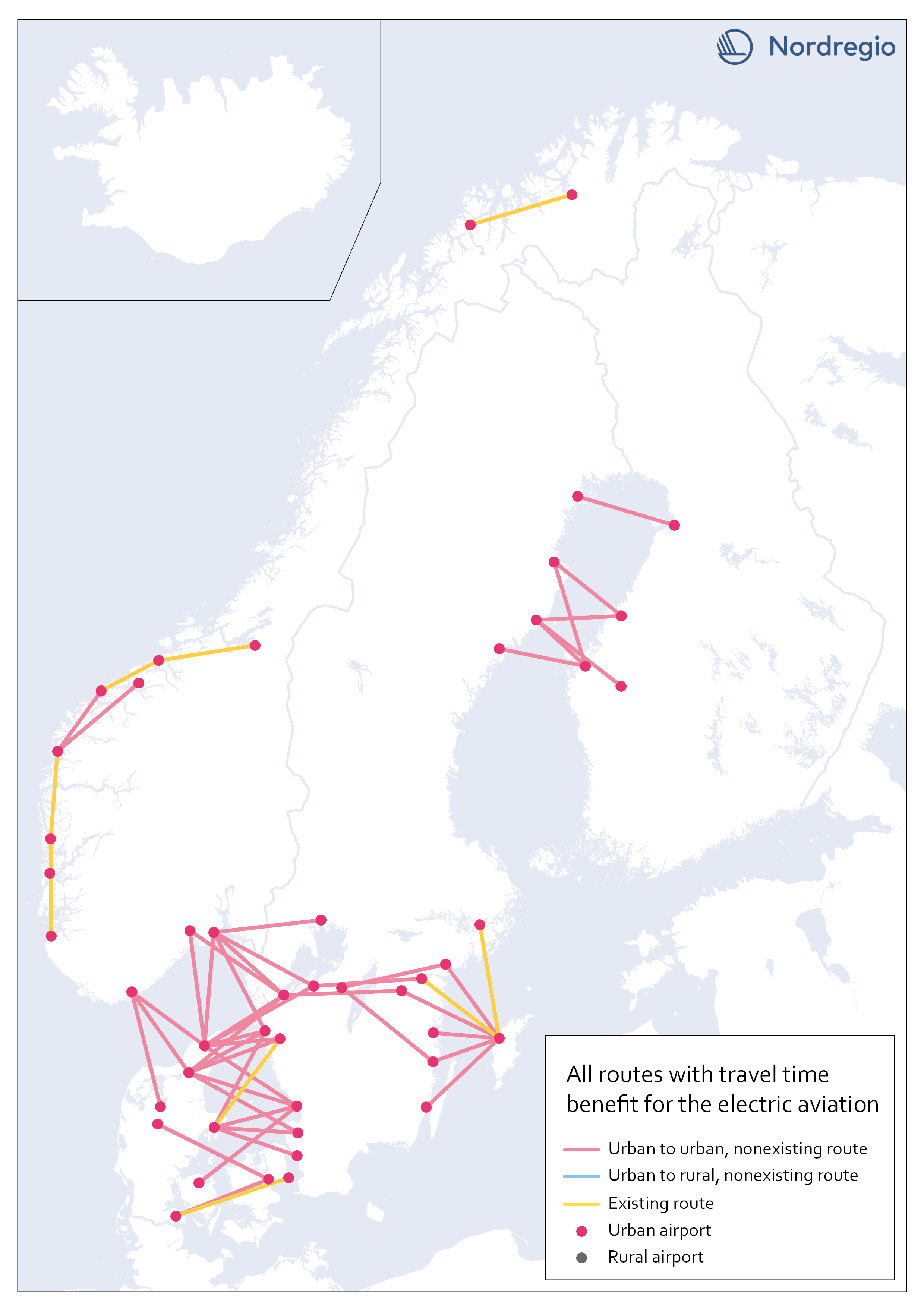

Electric aviation time benefits between urban areas separated by water

The map shows all routes between urban areas separated by water, and where electric aviation has significant time benefits compared to the fastest traffic mode. Yellow lines are already served by aviation, while red color indicates non-existent routes where electric flight would reduce the travel time between destinations. The result is in line with our assumptions, that there is a lack of fast connections between potential labor markets in urban areas, which are geographically close but separated by open water.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

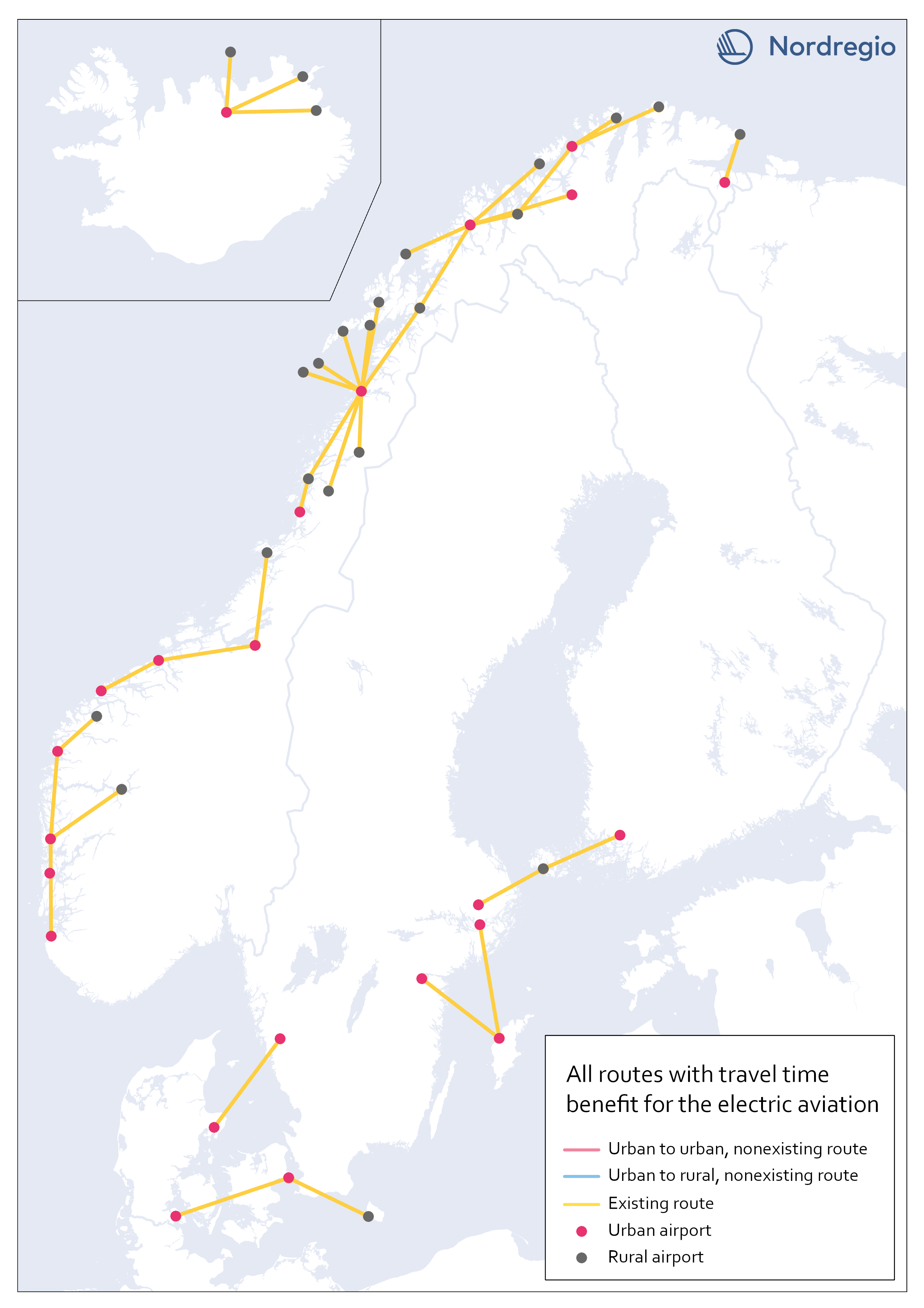

Existing routes with time benefit for electric aviation

The map visualizes all routes with significant travel time benefit, which are already served with commercial flights. Information on existing routes has been obtained from the report Nordic Sustainable Aviation (Ydersbond et al, 2020) and applies to the year 2019. Since then, routes may have been added or removed, which is important to bear in mind in future investigations. However, choosing a later year risk giving equally misleading results, as flights decreased drastically during the pandemic. Statistics for 2019 provide a picture of the demand that existed before the pandemic, which is the latest stable levels that can be obtained. Whether air traffic will ever return to the same levels as before the pandemic is too early to say. The majority of routes are found in Norway, along the coastline, which confirms earlier knowledge that Norway has a more extensive and coherent aviation network than the rest of the Nordic region.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

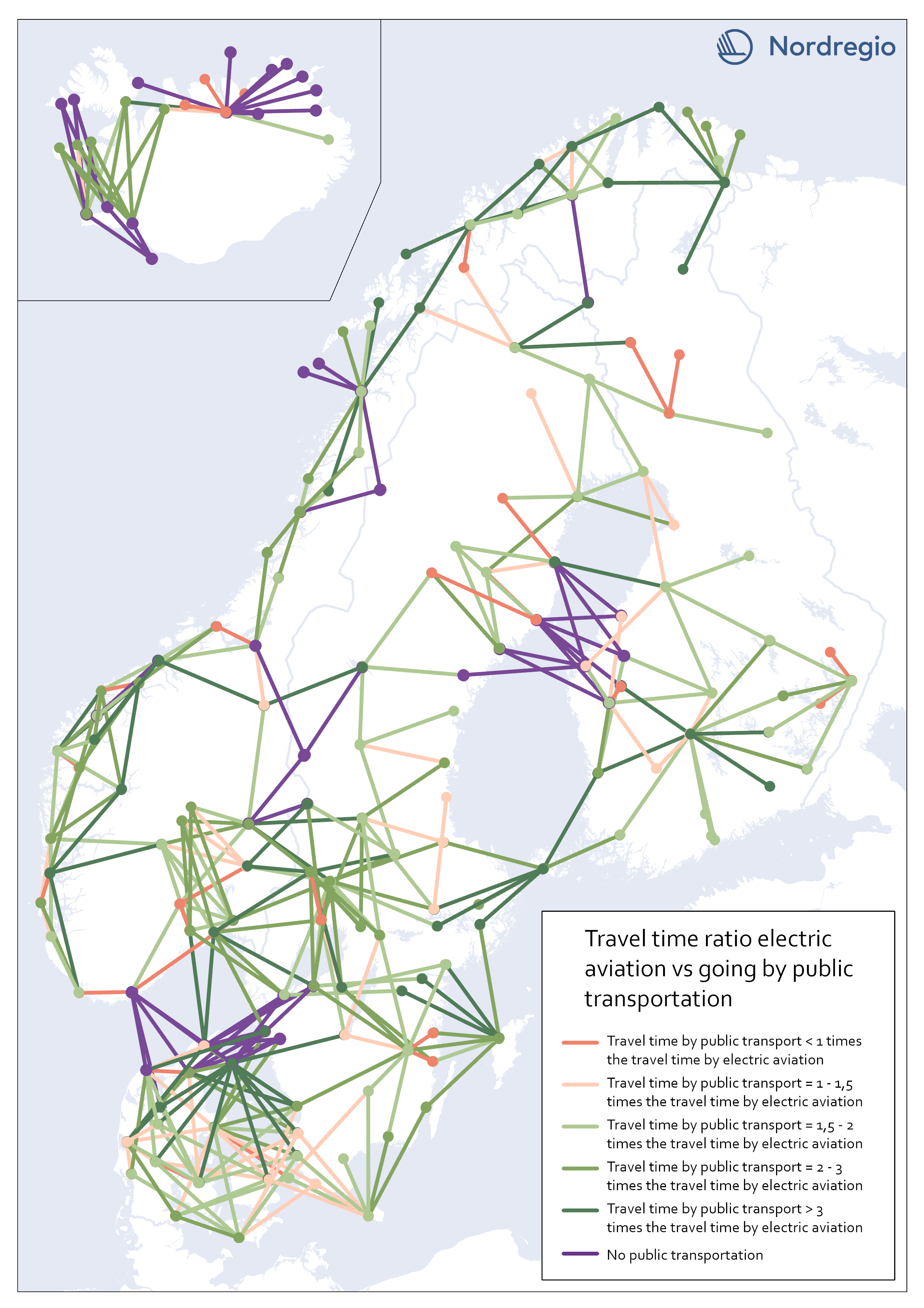

Travel time ratio – electric aviation vs public transportation

This map shows the travel time calculations for electric aviation versus travelling by public transportation. Routes represented by any nuance of green, are routes with significant travel time benefits for electric aviation in comparison with public transportation. The darker the nuance of green, the larger time benefit for electric aviation. The beige color represents routes where the travel time for public transportation is the same or up to 1,5 times the travel time for electric aviation. The red color represents routes where public transportation is faster than electric aviation. Purple lines represent routes where no public transportation is available. These were also routes where we could see significant time benefits for electric aviation. The number of changes when commuting with public transport may have a negative impact on perceived accessibility. In this accessibility analysis, however, we stay with the same criteria for public transport as for travel by car. For future research, the number of changes when commuting by public transport could be considered in the comparison.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

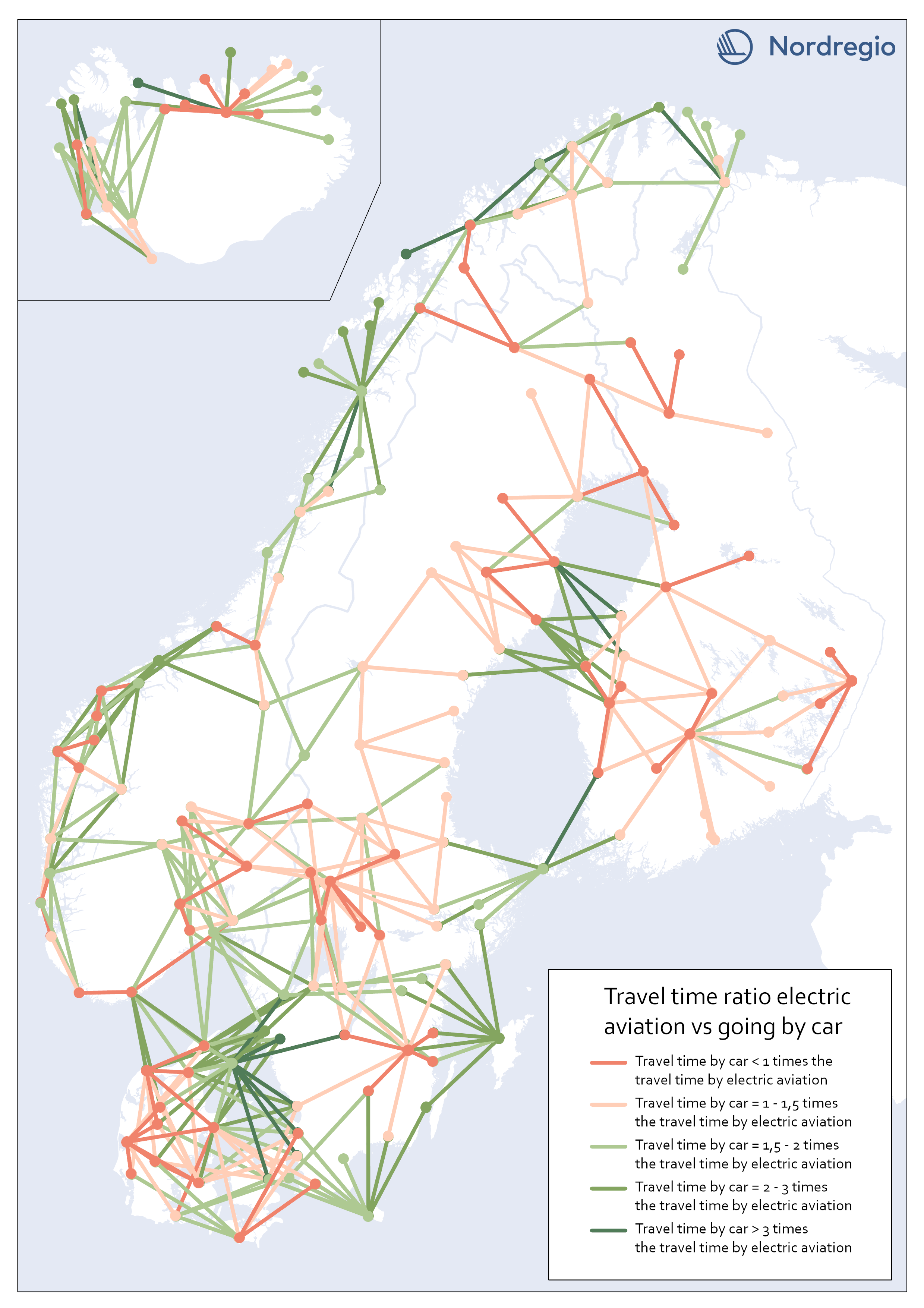

Travel time ratio – electric aviation vs car

This map shows the travel time calculations for electric aviation versus traveling by car. Routes represented by any nuance of green, are routes with significant travel time benefits for electric aviation in comparison with car. The darker the nuance of green, the larger time benefit for electric aviation. The beige color represents routes where the travel time for car is the same or up to 1,5 times the travel time for electric aviation. The red color represents routes where car is faster than electric aviation.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

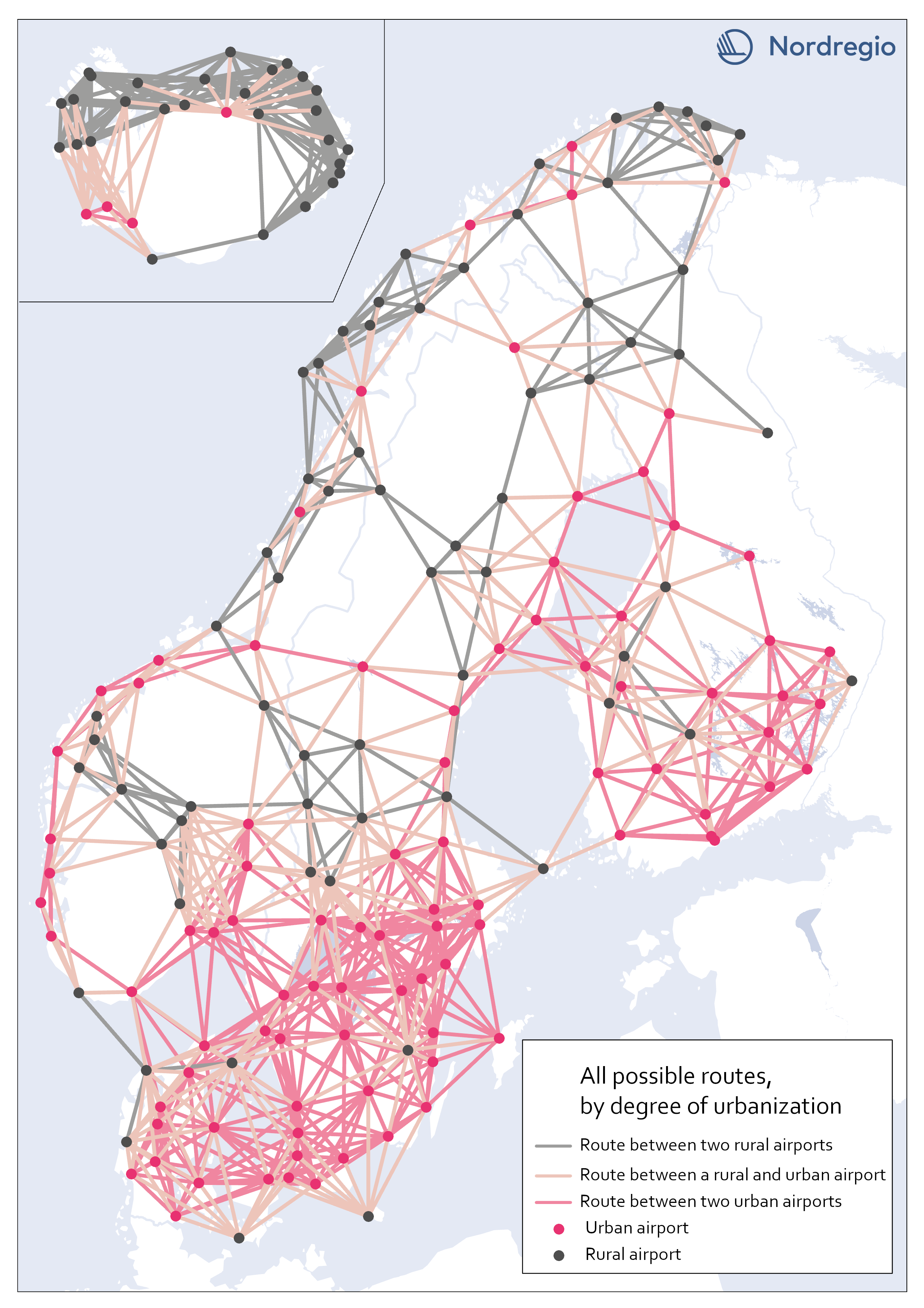

All possible electric aviation routes by a degree of urbanisation

The map shows all routes with a maximum distance of 200 km divided into three categories, based on the airports’ degree of urbanization: Routes between two rural airports, routes between one rural and one urban airport and routes between two urban airports. The classification is based on the new urban-rural typology. We restricted the analysis to routes between rural and urban areas as well as routes between urban areas that are separated by water. Those are 426 in total. We based our criteria on the assumption that accessibility gains to public services and job clusters can be made for rural areas, if better connected to areas with a high degree of urbanization. Because of possible potential to link labor markets between urban areas on opposite sides of water urban to urban areas that cross water are also included. This is based on previous research which has shown the potential for electric aviation to connect important labor markets which are separated by water, particularly in the Kvarken area (Fair, 2022). Our choice of selection criteria means that we intentionally ignore routes where electric aviation may have a potential to reduce travel times significantly. There might also be other important reasons for the implementation of electric aviation between the excluded routes. Between rural areas, for example, tourism or establishing a comprehensive transport system in the Nordic region, constitute reasons for implementing electric aviation. Regarding routes between urban areas over mainland, the inclusion of more routes with the same rationale as above – that significant time travel benefits could be gained between labor markets with electric aviation (for example between two urban areas in mountainous regions where travel times can be long) – can be motivated. Some of those routes can be important to investigate at a later stage but are outside the…

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

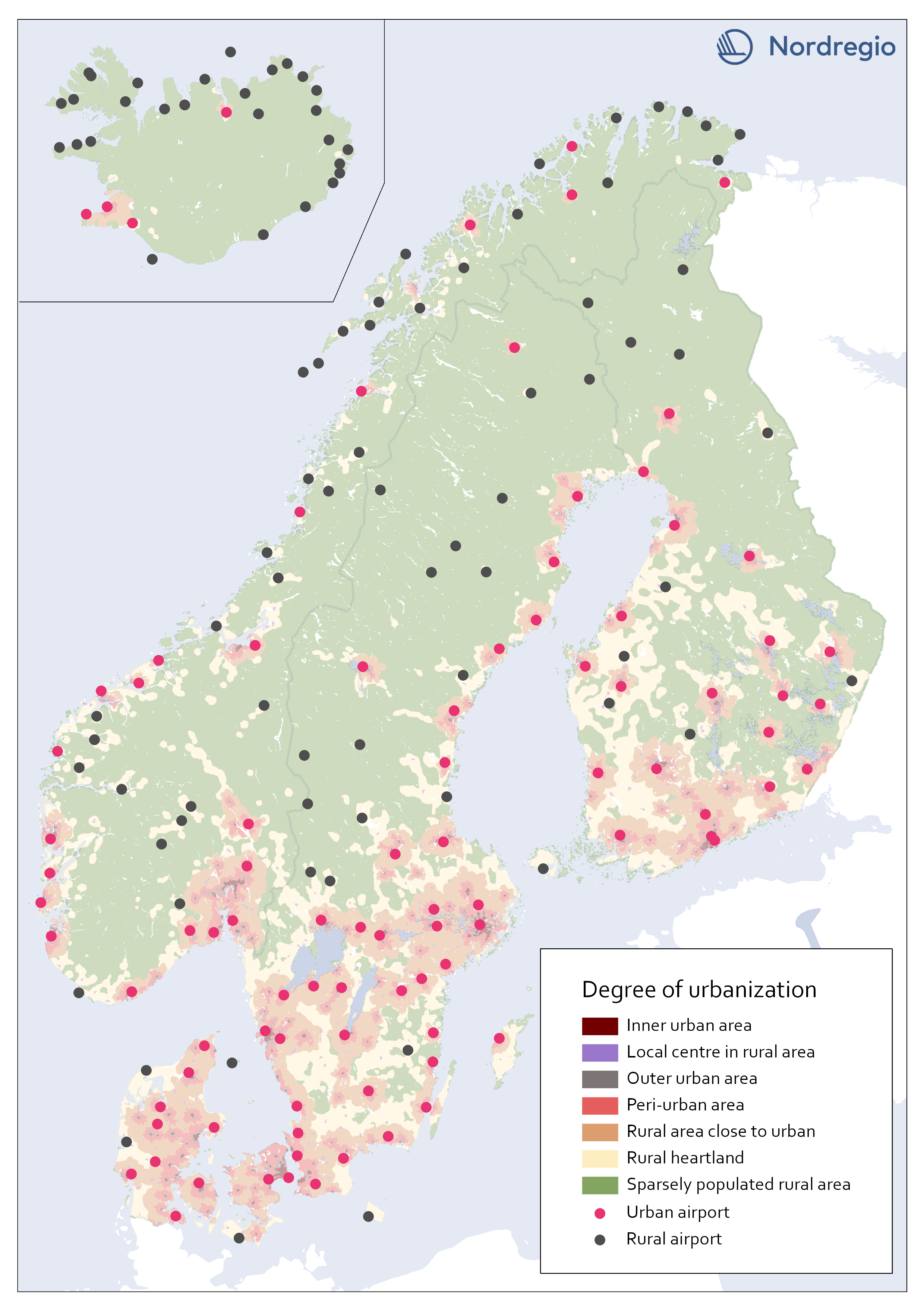

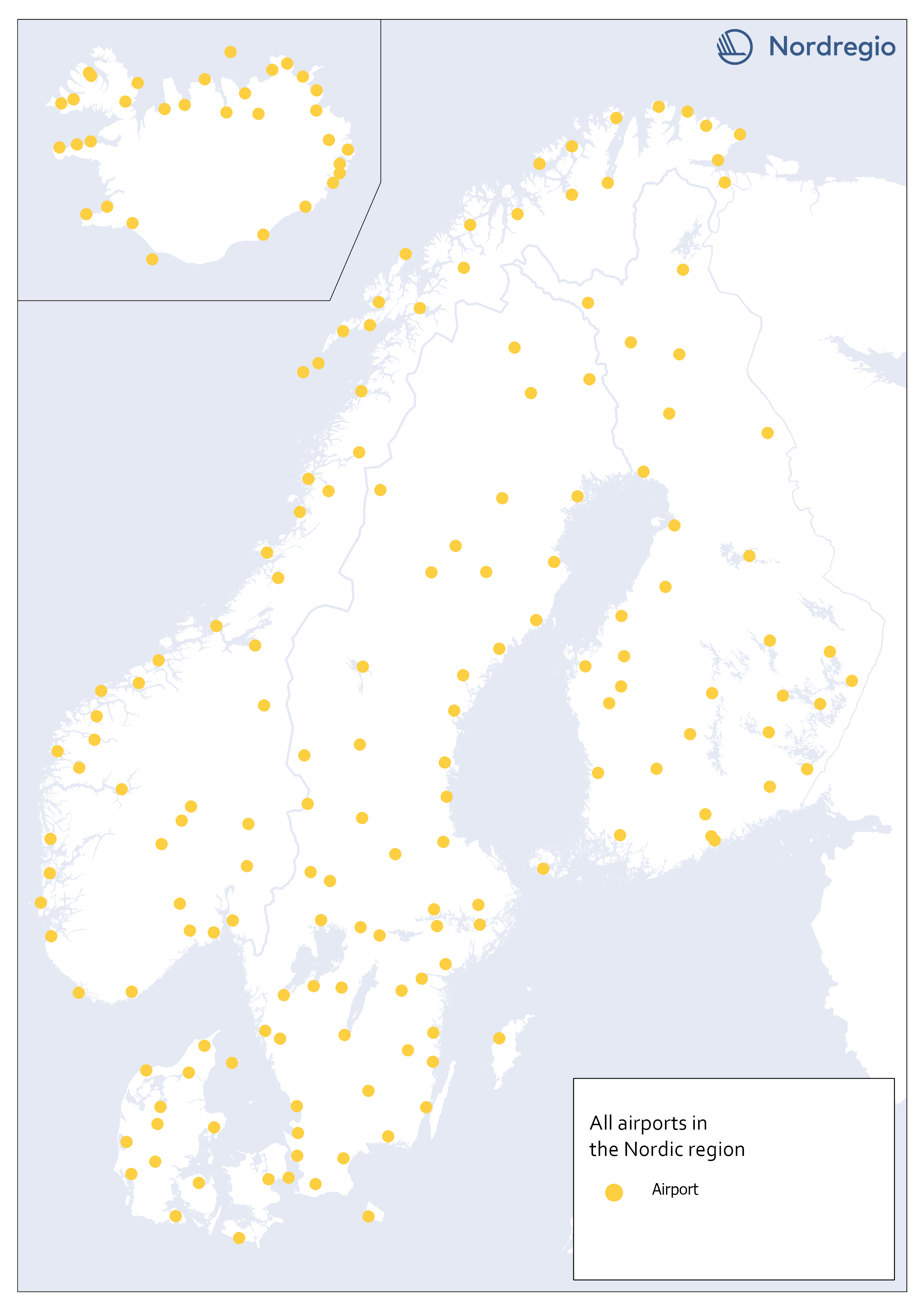

All airports in the Nordic region by a degree of urbanisation

This map classifies all airports by a degree of urbanisation. The classification is based on the new urban-rural typology. We classified all airports localized within any of the top five urbanization classes (Inner urban area, Local center in rural area, Outer urban area, peri-urban area, or Rural area close to close to urban) as Urban. All other airports, localized within the bottom two classes (Rural heartland or Sparsely populated rural area) were classified as Rural. No adjustments were made based on the proximity of the airports to urban areas. During the process we considered adjustments in the categorization based on the airports’ potential catchment area from a close urban area. For example, one can assume that Gällivare Lappland airport in the north of Sweden, has its main catchment area from Gällivare which is classified as a local center in rural area (i.e. Urban). The airport, though, is localized within the category Rural heartland. Yet, we decided to let the typology determine to which category each airport belong.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

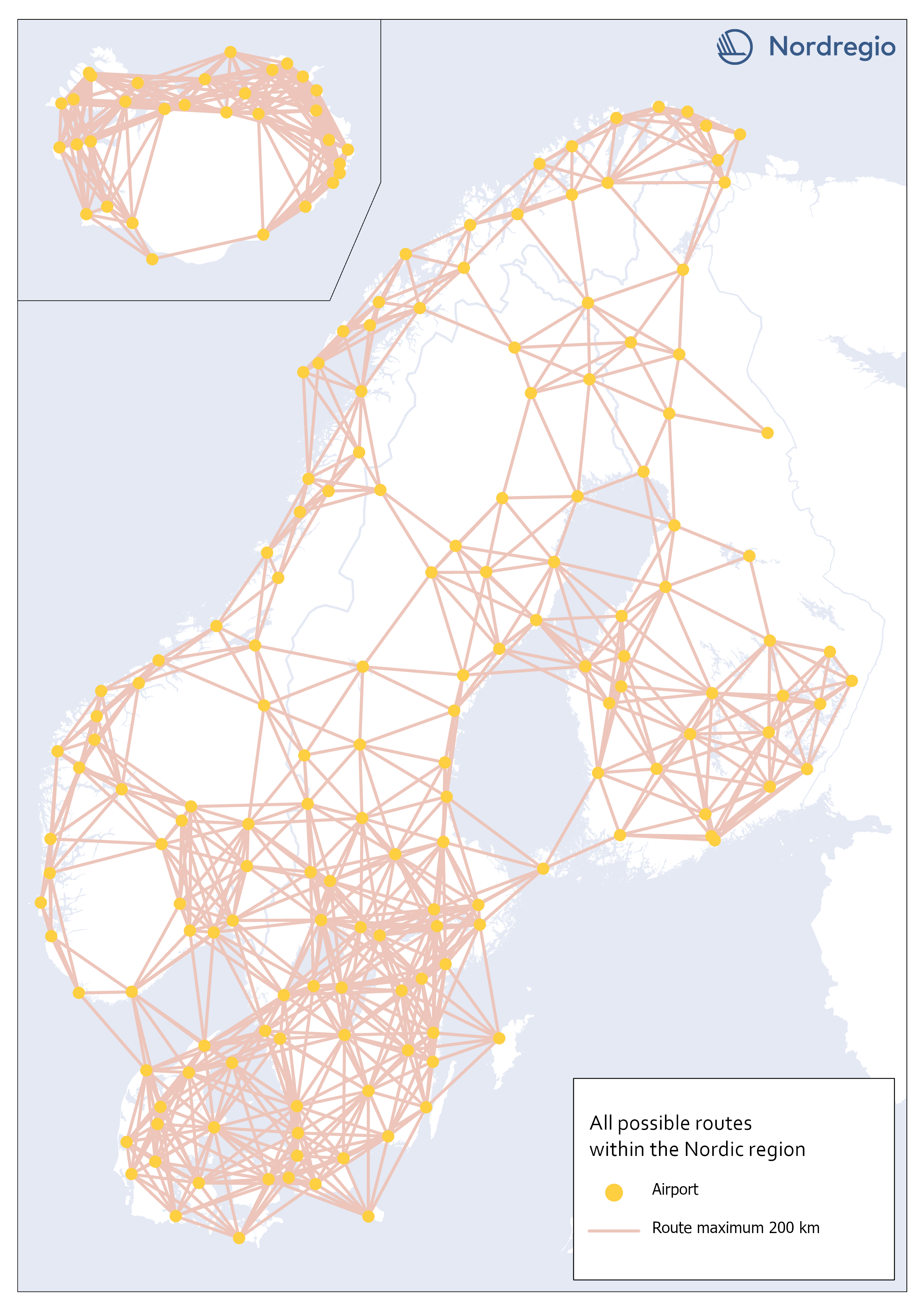

All possible electric aviation routes, max 200km, within the Nordic region

This map shows all possible electric aviation routes of a maximum distance of 200 kilometres within the Nordic region. First generation electric aviation will have a limited range due to battery capacity. According to the report Nordic Sustainable Aviation, routes up to 400 kilometers constitute an initial market for electric airplanes in the Nordic region. However, also shorter distance routes under 200 km, where cruise speed is less important and in sparsely populated regions where passenger volumes are very small, will be the focus (Ydersbond et al, 2020). The first generation of aircrafts that rely solely on electric power have a defined maximum range of 200 km (Heart Areospace, 2022). For this accessibility study, we only included routes of a maximum distance of 200 kilometers. This selection gave us 1001 possible routes in total.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

All airports in the Nordic region

This map shows all airports within the geographical scope which may be operated with commercial flight. To limit our selection of airports, we used a combination of two official airport code systems: IATA (International Air Transport Association) and ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization). IATA-codes specify the airport as a part of a commercial flight route. However, the IATA system, is not solely limited to airports. Other locations, such as bus or ferry stations can also apply for an IATA location code, as long it is included in an airline travel chain. The ICAO-code, on the other hand, indicates that the location is an airport, but not necessarily for commercial flights In order to obtain a selection of airports that met our criteria, an airport was included only if it had both an IATA-code and an ICAO-code. Three different sources are used: 1) Swedavia (lists all airports in the Nordics that Swedavia traffics today). This is our main source, but it does not include all existing airports in the Nordic countries. Therefore, we also use two other sources: 2) Avcodes: Airport code database, from which other airports, that are not served by Swedavia, are obtained. 3) Wikipedia. Finally, the listed airports are checked against Wikipedia, to verify if any airports have been missed through the other sources. This selection gave us 186 airports in total.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

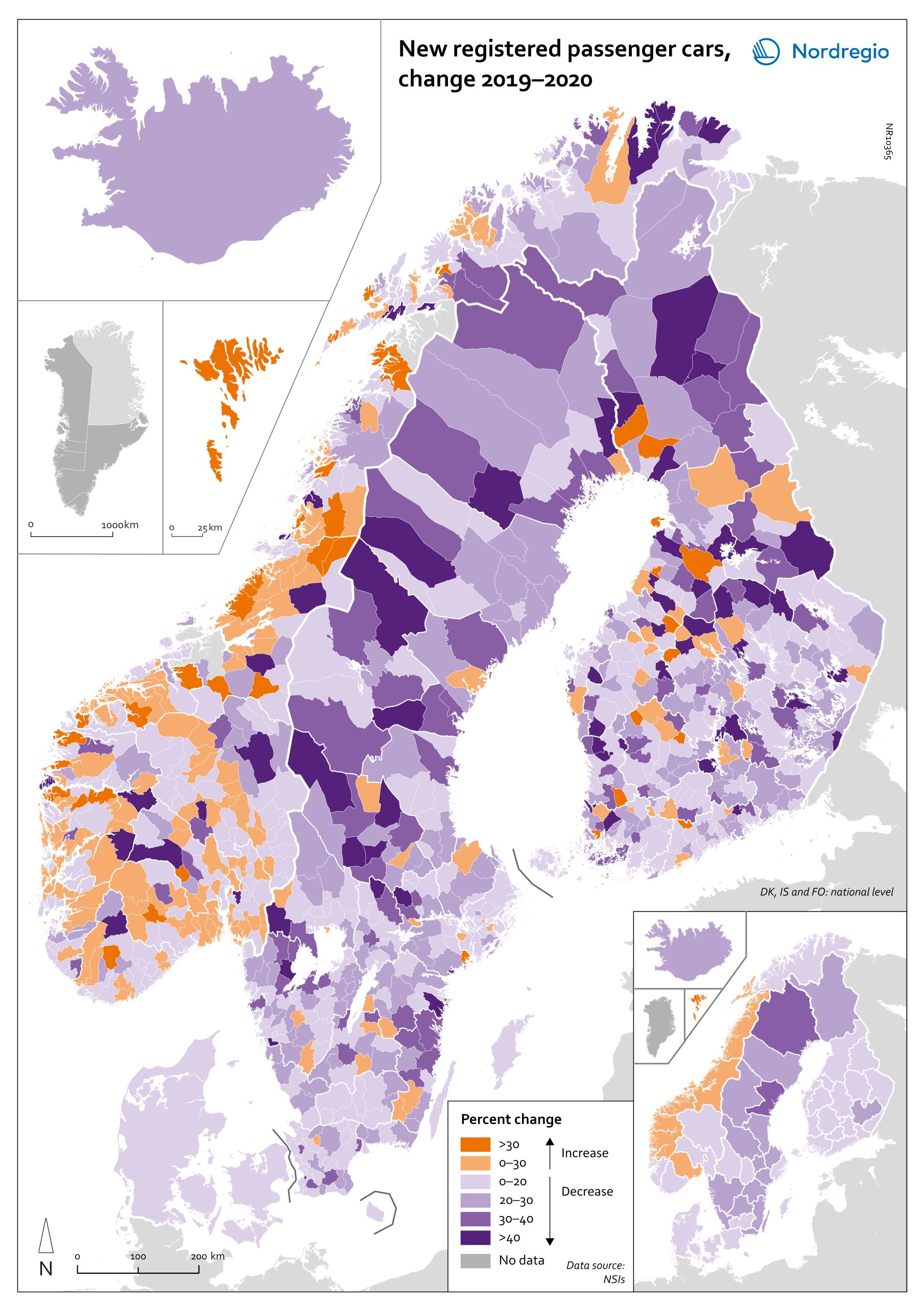

Change in new registered cars 2019-2020

The map shows the change in new registered passenger cars from 2019 to 2020. In most countries, the number of car registrations fell in 2020 compared to 2019. On a global scale, it is estimated that sales of motor vehicles fell by 14%. In the EU, passenger car registrations during the first three quarters of 2020 dropped by 28.8%. The recovery of consumption during Q4 2020 brought the total contraction for the year down to 23.7%, or 3 million fewer cars sold than in 2019. In the Nordic countries, consumer behaviour was consistent overall with the EU and the rest of the world. However, Iceland, Sweden, Finland, Åland, and Denmark recorded falls of 22%–11% – a far more severe decline than Norway, where the market only fell by 2.0%. The Faroe Islands was the only Nordic country to record more car registrations, up 15.8% in 2020 compared to 2019. In Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, there were differences in car registrations in different parts of the country. In Sweden and Finland, the position was more or less the same in the whole of the country, with only a few municipalities sticking out. In Finland and Sweden, net increases in car registrations were concentrated in rural areas, while in major urban areas, such as Uusimaa-Nyland in Finland and Västra Götaland and Stockholm in Sweden, car sales fell between 10%–22%. Net increases in Norway were recorded in many municipalities throughout the whole country in 2020 compared to 2019.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Transport

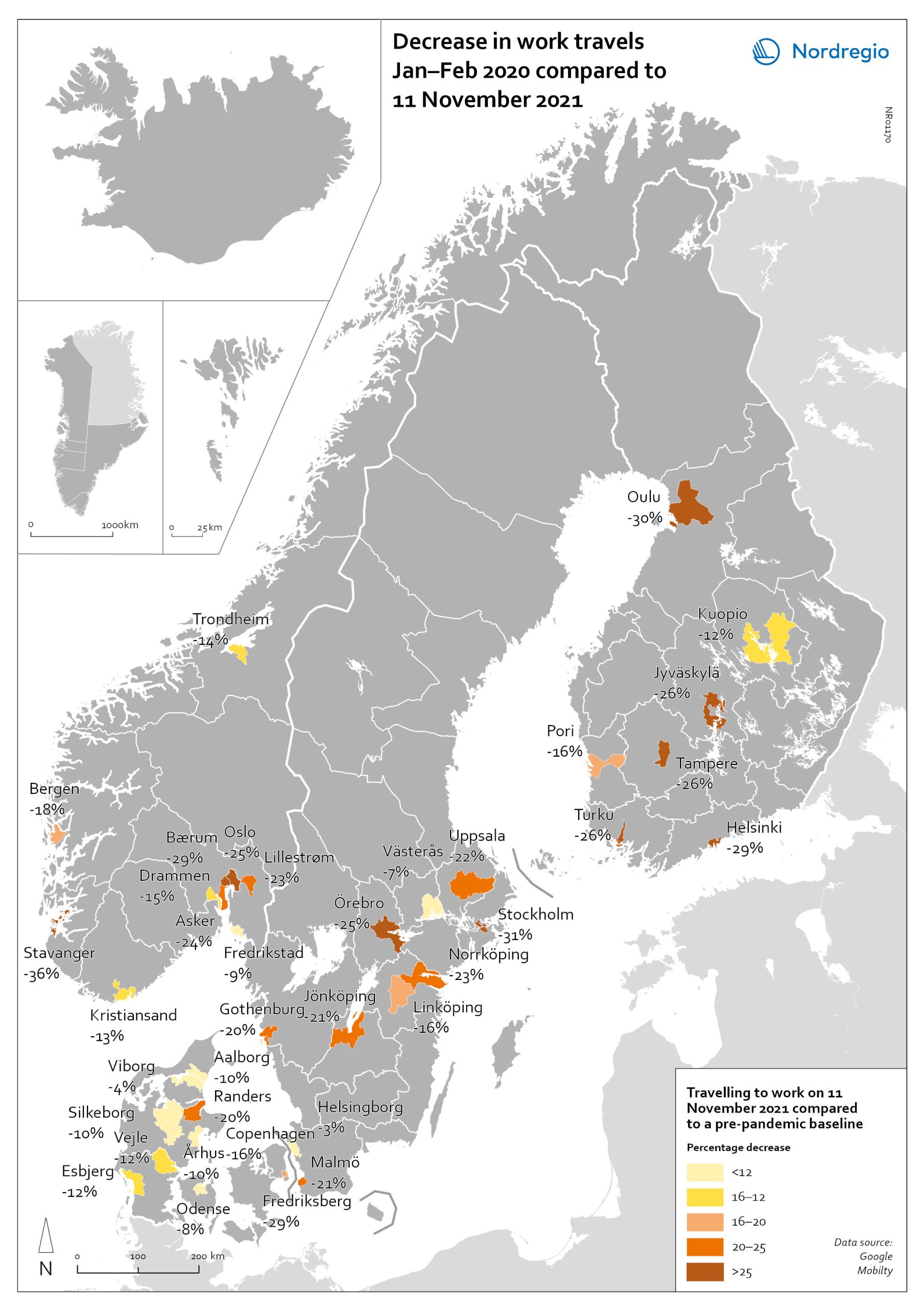

Change in work travels Jan-Feb 2020 compared to Nov 2021

The map shows changes in number of people travelling to work in the Nordic municipalities with the biggest populations comparing November 2021 to a pre-pandemic baseline. The map compares the average number of people who travelled to work on a weekday in January and February 2020 with the number of people who travelled to work on 11 November 2021 in the ten largest cities of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. The date was selected as the reference date as it is considered to be a relatively typical Thursday. It also represents a point when few movement restrictions were in place in the Nordic countries. As can be seen from the map, all of the municipalities highlighted recorded a fall in work-related travel on 11 November compared to the pre-pandemic baseline. It was biggest in Stavanger (-36%), followed by Stockholm (-31%), Oulu (-30%), Bærum (adjacent to Oslo) (-29%), Frederiksberg (adjacent to Copenhagen) (-29%) and Helsinki (-29%). In general, the decrease was highest around the capital regions and larger cities, but there were exceptions, for example, Jyväskylä (-26%), Örebro (-25%), Jönköping (-21%), and Randers (-20%). Several large municipalities also stood out because their patterns did not change so much, for example, Helsingborg (-3%) and Västerås (-7%) in Sweden; Viborg (-3%) and Odense (-8%) in Denmark.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

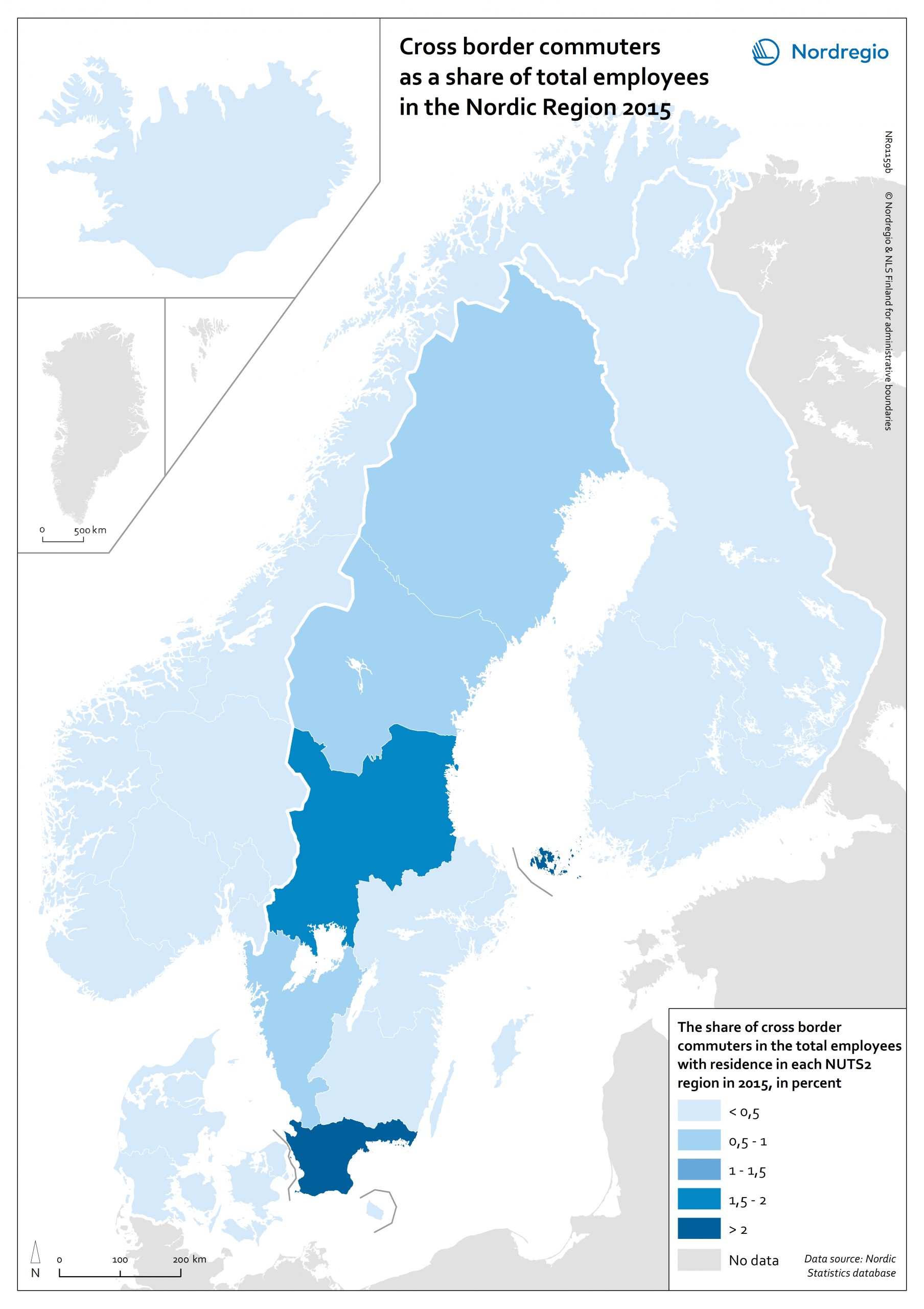

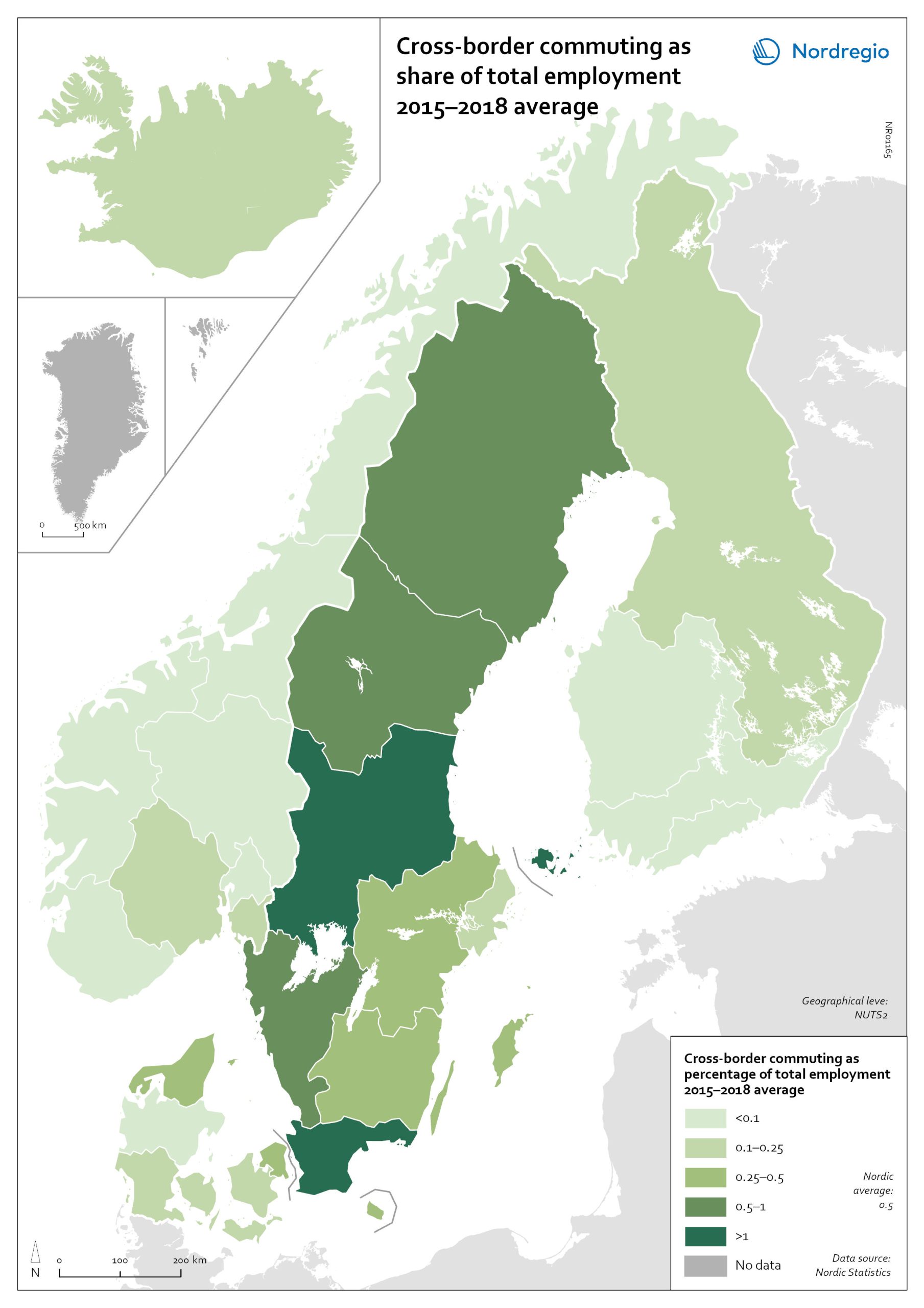

Cross-border commuting as share of employment

The map illustrates the average share of employees who commuted to another Nordic country between between 2015 and 2018 in Nordic regions (NUTS 2). Between 2015 and 2018, an average of approximately 49,000 people held a job in a Nordic country in which they were not residents. This indicates that, on average, 0.5% of the Nordic working-age population commuted to a job in another Nordic country. This is below the EU27 average of 1%, with the highest numbers found in Slovakia (5.1%), Luxembourg (2.8%) and Estonia (2.6%). Some of these people cross borders daily. Others work in another country by means of remote working combined with occasional commuting across borders. Within the Nordic Region, the largest cross-border commuter flows are in the southernmost parts of Sweden, regions in the middle of Sweden and in Åland, where more than 1% of the working population commutes to another Nordic country. However, there may be individual municipalities where cross-border commuting is substantially higher. For example, the employment rate in Årjäng Municipality, Sweden, increases by 15 percentage points when cross-border commuting is taken into account. These municipalities are not reflected on NUTS 2 level when averages are calculated. In terms of absolute numbers in 2015, the highest numbers of commuters were from Sweden: Sydsverige (16,543), Västsverige (7,899) and Norra Mellansverige (6,890). The highest number of commuters from a non-Swedish region were from Denmark’s Hovedstaden (2,583). Due to legislative barriers regarding the exchange of statistical data on cross-border commuting between the Nordic countries, more recent data is not available.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

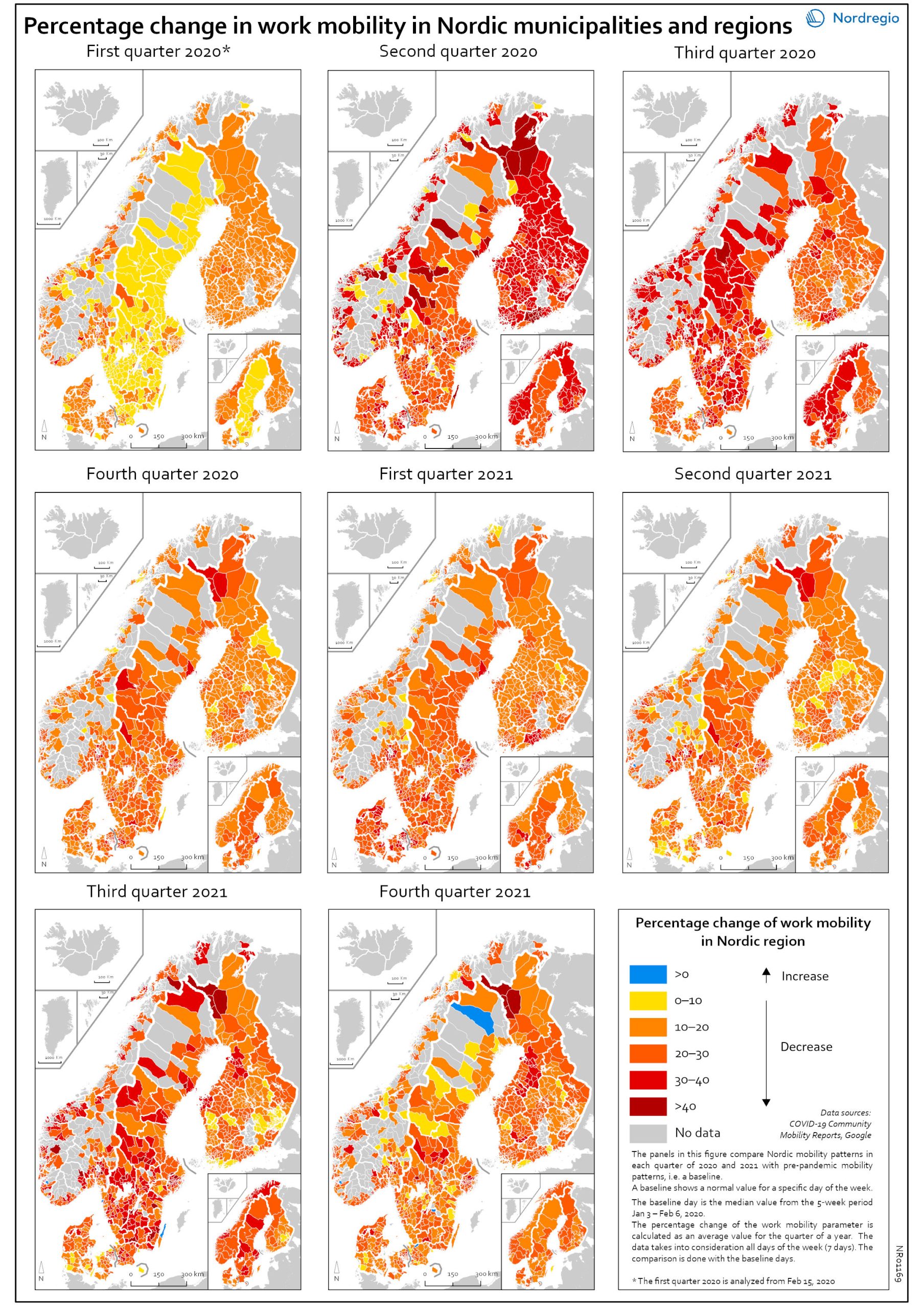

Work mobility per municipality and region by quarter

The map shows the percentage change for work mobility in Nordic regions and municipalities compared to a pre-pandemic baseline. The maps compare Nordic mobility patterns in each quarter of 2020 and 2021 with a pre-pandemic baseline. Based on Google data, the panels illustrate the impact of national restrictions and how those restrictions hampered work mobility. As the restrictions were both national and regional in nature, some regions and municipalities were more affected than others. The darker areas in the map show that work mobility decreased the most Q2 and Q3 2020 and in Q3 2021. The panels also show that mobility decreased later in Sweden than in the other Nordic countries. However, the decrease in Q3 in both 2020 and 2021 may partly be explained by the summer vacation months, when work mobility tends to decrease anyway. In Q4 2021, the overall situation seems to improve, although the pattern is mixed. In a few municipalities the situation is almost back to pre-pandemic baseline while in most municipalities, there is still less mobility in the labour market compared to the pre-pandemic situation.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

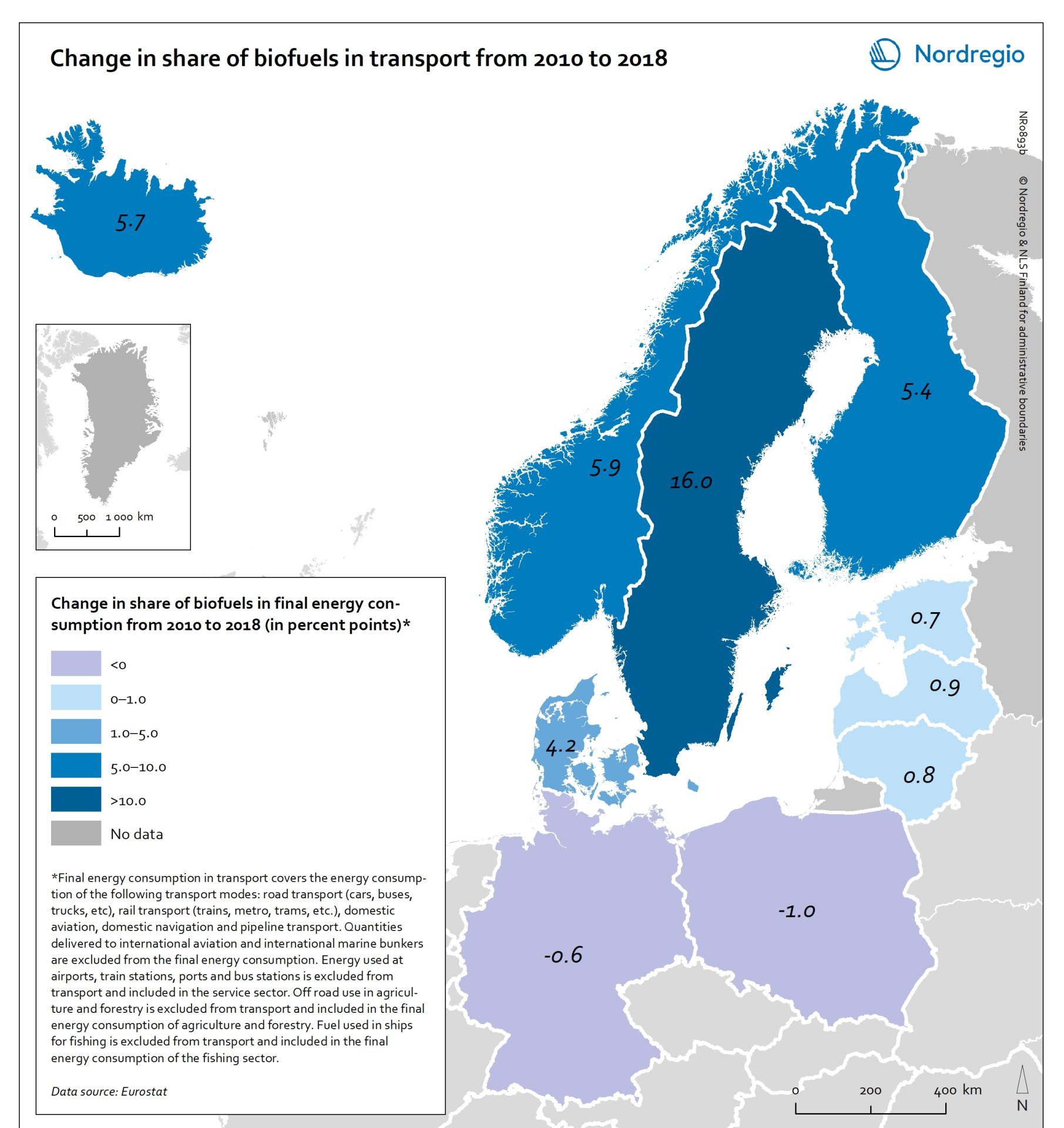

Change in share of biofuels in transport from 2010 to 2018

This map shows change in share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region from 2010 to 2018. Even though a target for greater use of biofuels has been EU policy since the Renewable Energy and Fuel Quality Directives of 2009, development has been slow. The darker shades of blue on the map represent higher increase, and the lighter shades of blue reflect lower increase. The lilac color represent decrease. The Baltic Sea represents a divide in the region, with countries to the north and west experiencing growth in the use of biofuels for transport in recent years. Sweden stands out (16 per cent growth), while the other Nordic countries has experienced more modest increase. In the southern and eastern parts of the region, the use of biofuels for transport has largely stagnated. Total biofuel consumption for transport has risen more than the figure indicates due to an increase in transport use over the period.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

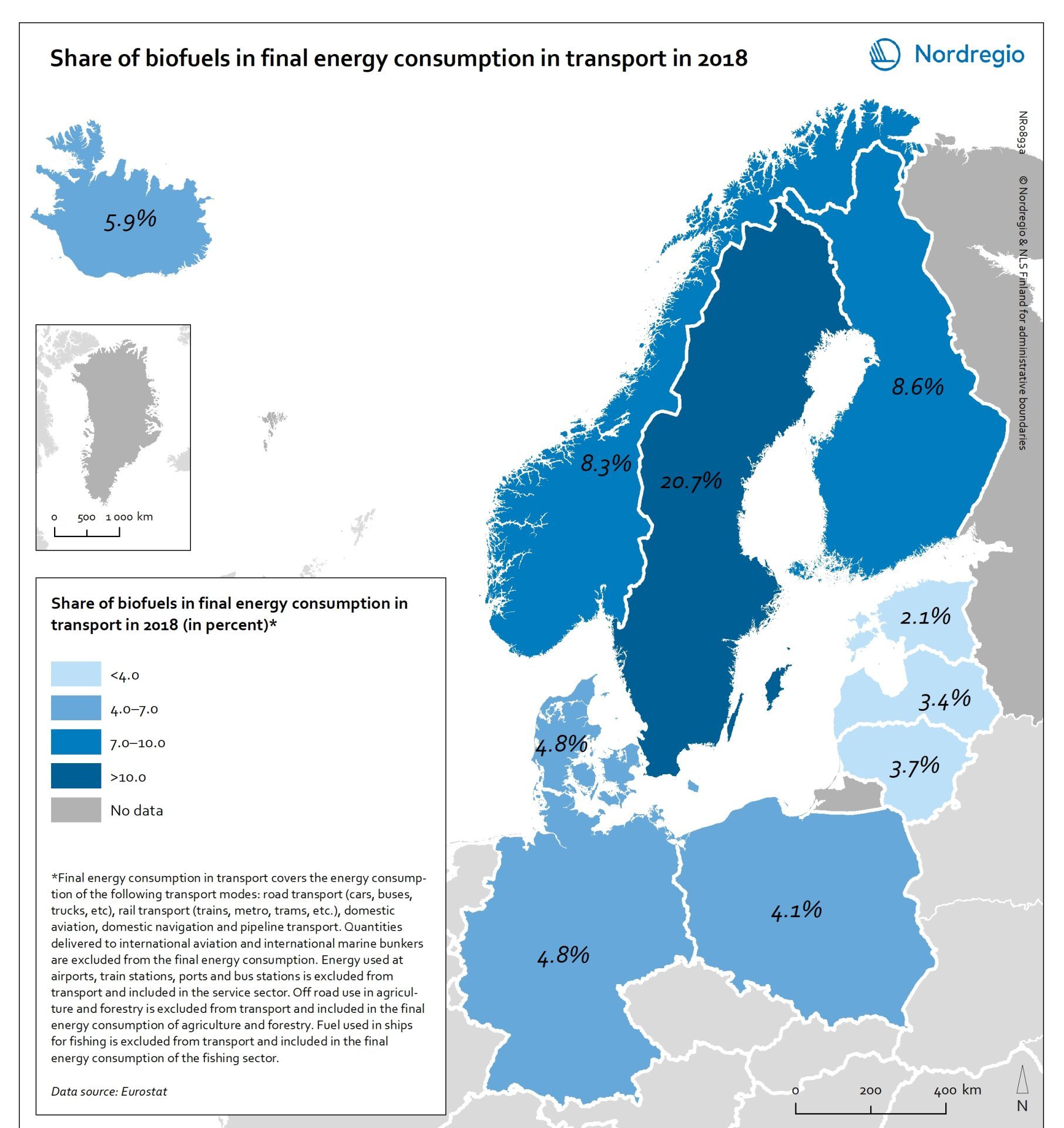

Share of biofuels in transport in 2018

This map shows the share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region in 2018. There has been considerable political support for biofuels and in the EU, this debate has been driven by the aim of reducing dependency on imported fuels. For instance, 10 per cent of transport fuel should be produced from renewable sources. The darker shades on the map represent higher proportions, and the lighter shades reflect lower proportions. As presented by the map, only Sweden (20.7%) had reached the 10 per cent target in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Region in 2018. Both Finland (8.3%) and Norway (8.3%) were close by the target, while the other countries in the region were still lagging behind, particularly the Baltic countries.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport