293 Maps

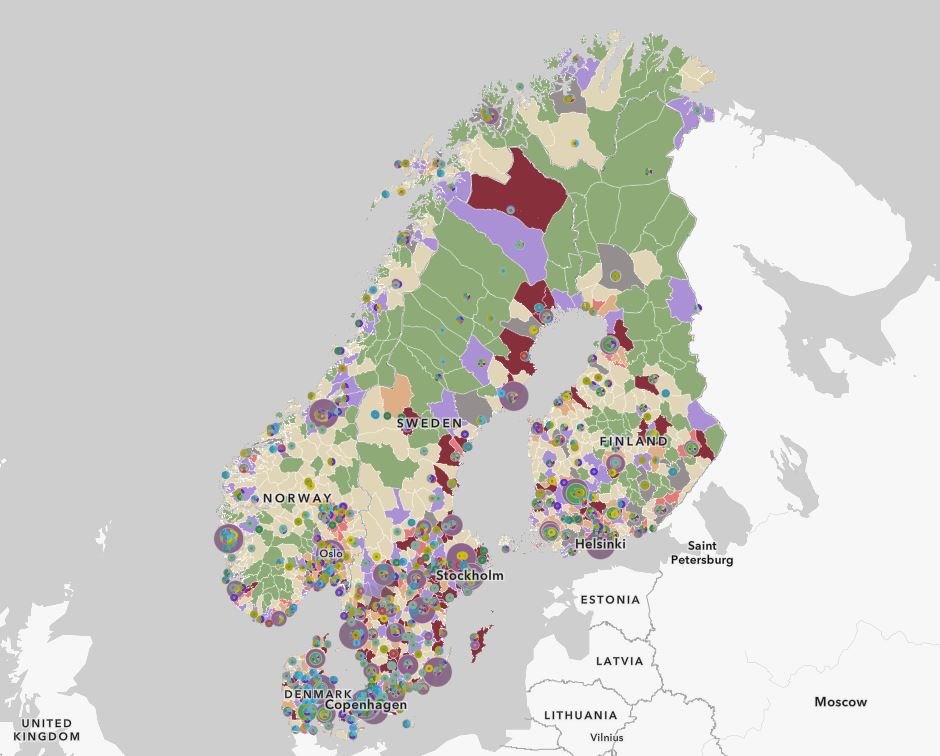

EDYNORA Higher Education and VET Portal

The portal provides a visual and analytical overview of the diversity of campuses and independent institutions across the Nordic countries. It offers information on each campus’ or institution’s location, the fields of education offered, the number of students and the year of establishment. Data are presented across different institutional types, classified according to the highest level of education provided at a given campus or institution (in the case of single-campus institutions). The data for the portal were sourced primarily from institutional websites (e.g., “About Us” pages and annual reports), as well as statistical databases (the Vipunen database in Finland and the Database for Statistics on Higher Education (DBH) in Norway. The portal is intended for educational authorities, policymakers, and education providers seeking inspiration, collaboration opportunities, and insights into key figures and the distribution of education across the Nordic region.

2025 June

- Education

- Nordic Region

Foreign-born share 2022

This map shows the share of foreign-born of the total population in the Nordic countries. This map shows the share of foreign-born of the total population in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map), and municipalities (big map) in 2022. Iceland has the highest share of foreign-born residents in the Nordic Region, at 22%. Mýrdalshreppur, the municipality in the south containing the village of Vik, has the largest foreign-born population, at 58%. It is also the only municipality in the Nordic Region with a majority non-native population. Other municipalities in the south, some of which are quite small, also have significant foreign-born populations. Reykjanesbær, near Keflavik airport, is the largest municipality with a sizeable foreign-born population, at 29%. In Reykjavíkurborg, 20% of the population is foreign-born, about the same as the national average. Many municipalities with tiny populations in the Westfjords and the north also have small shares of foreign-born persons. In 2022, 17% of the population of Norway was foreign-born. Municipalities with high shares of foreign-born include Oslo (28%), several suburban municipalities near Oslo, and a few in the north – which have small overall populations but large numbers of foreign workers employed in the fishing industry. In Sweden, 20% of residents are foreign-born, with large differences in distribution by region and municipality. At the regional level, Stockholm has the highest share of foreign-born persons (27%), followed by Skåne, including the city of Malmö (24%). The percentage of foreign-born persons in Västra Götaland, which encompasses Gothenburg, is the same as that of Sweden as a whole. The regions with low shares of foreign-born persons are in the north of the country – Dalarna, Gävleborg, Västernorrland, Jämtland, Västerbotten, and Norrbotten – plus the island of Gotland, which has the lowest share (9%). There are no municipalities in which foreign-born…

2025 April

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Foreign-born change (%) 2000-2022

This map shows the percentage-point change in foreign-born populations in the Nordic countries. This map shows the percentage-point change in foreign-born populations by region (small map) and municipality (big map) between 2000 and 2022. The blue shades indicate an increase in the number of foreign-born while the red shades indicate a decrease. The recent growth in foreign-born populations differs among the Nordic countries, regions, and municipalities. During the period 2000-2022, much of both the absolute and percentage-point increases in the foreign-born populations took place in suburbs around the capital cities and other large urban centres. However, with few exceptions, every municipality across the Nordic Region saw increases in foreign-born populations. In Iceland, the foreign-born population increased from 5% to 20%. The largest percentage-point increases in the foreign-born populations were in municipalities in the southwest, which had small populations and small foreign-born shares. Of the larger municipalities, Reykjanesbaer and the Capital Region had the largest absolute and percentage point increases. The foreign-born population in Norway grew from 7% to 17%. The municipalities with significant increases in foreign-born populations include several suburban areas near Oslo, as well as scattered municipalities elsewhere that had small foreign-born shares in 2000. The percentage of foreign-born residents in Oslo increased from 16% to 28% between 2000 and 2022. No municipalities experienced a decline in foreign-born population during this period.

2025 April

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Women in childbearing ages 2022

This map shows the number of women in childbearing age as a percentage of the total population in the Nordic countries. This map shows the number of women in childbearing ages as percent of total population in the Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map) in 2022. At the national level, Greenland and Iceland have the largest shares of women of childbearing age (15–45 years), more than 20%. Next are Norway, Denmark and Sweden, with somewhat lower shares, 18–19%. The lowest share, less than 18%, is in Finland, where there have been more deaths than births since 2016. The Faroes and Åland both have shares of less than 17%. Municipalities in Greenland and Iceland follow the national trends, mostly with shares of women of childbearing age of 20–25%, although some are higher than 25%. In the other countries, municipalities in and around the capitals and other large cities have larger shares, 20% or higher. Most regions outside of the large cities have smaller shares, between 15 and 20%. Many regions in Finland have older populations, and these have shares of less than 10%. The lack of women of childbearing age, combined with those of childbearing age having so few children, means that there will be fewer births in these municipalities in the future, leading to further population decline.

2025 April

- Demography

- Nordic Region

Total fertility rate (TFR) 2022

This map shows the total fertility rate (TFR) in 2022. The total fertility rate is the number of children a hypothetical cohort of women would have in one year. Data on total fertility rates is not available at the regional or municipal levels for all of the Nordic countries. The figures are estimated based on multiplying the general fertility rate by 30 (representing the typical number of reproductive years, between 15 and 45), assuming the general fertility rate is constant throughout this period. The general fertility rate is the number of births per woman during the childbearing years. At the regional level, age and gender composition are indicative of past trends but also harbingers of future population change. In 2018, prior to the pandemic, most Nordic municipalities had fertility levels in line with their respective national levels (see map Total fertility rate (TFR) 2018 in Nordregio’s Map Gallery). Most municipalities within Greenland and the Faroes had fertility rates above 1.5 children per woman, consistent with national rates of about 1.9 (2018 map). Municipalities in Sweden and Denmark typically had fertility rates of 1.5 or higher, consistent with their national rates of 1.7. By contrast, many municipalities in Norway and Finland had fertility rates of 1.5 or lower. In 2022, fertility in most municipalities across the Nordic Region fell, reflecting the declines at the national levels, but the spatial pattern had become slightly more varied (2022 map). In several municipalities in Norway, Finland, and Sweden, fertility rates fell to less than 1.0 children per woman. The drops in fertility resulted in declines in the number of births across most municipalities in 2022. Combined with increases in the number of deaths, this resulted in more deaths than births in many municipalities, consistent with trends at the national level. Most municipalities in Greenland,…

2025 April

- Demography

- Nordic Region

Total fertility rate (TFR) 2018

This map shows the total fertility rate (TFR) in 2018. The total fertility rate is the number of children a hypothetical cohort of women would have in one year. Data on total fertility rates is not available at the regional or municipal levels for all of the Nordic countries. The figures are estimated based on multiplying the general fertility rate by 30 (representing the typical number of reproductive years, between 15 and 45), assuming the general fertility rate is constant throughout this period. The general fertility rate is the number of births per woman during the childbearing years. At the regional level, age and gender composition are indicative of past trends but also harbingers of future population change. In 2018, prior to the pandemic, most Nordic municipalities had fertility levels in line with their respective national levels. Most municipalities within Greenland and the Faroes had fertility rates above 1.5 children per woman, consistent with national rates of about 1.9. Municipalities in Sweden and Denmark typically had fertility rates of 1.5 or higher, consistent with their national rates of 1.7. By contrast, many municipalities in Norway and Finland had fertility rates of 1.5 or lower. Iceland and Åland also showed varying rates across municipalities, ranging from 1 to over 1.5.

2025 April

- Demography

- Nordic Region

Internal Migration 2021

This map shows the internal net migration in 2021 as a percentage of the total population. This map shows the internal net migration in 2021 as a percentage of the total population. The small map shows the result on a regional level, and the big map on the municipal level. Internal (sometimes referred to as domestic) net migration refers to migration between municipalities and regions within the same country. International migration is excluded. In 2021, internal net migration was positive (indicated by shades of blue) or at least balanced (shown in yellow) in many of the municipalities in central and northern Sweden and in central and eastern Finland – areas that traditionally were more likely to lose population due to internal migration. Conversely, several municipalities in the capital regions – such as Stockholm, Oslo, and Copenhagen – exhibited negative internal net migration. Iceland, Greenland, and Åland exhibited mixed internal migration flows, with some municipalities experiencing positive net migration while others faced negative net migration. The Faroe Islands stand as an exception, maintaining only positive internal migration at the municipal level for this year.

2025 April

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Natural population increase 2022

This map shows the natural population change per 1,000 persons in 2022. This map shows the natural population change per 1,000 persons in 2022 (i.e. between 1 Jan and 31 Dec 2022). Natural population change refers to births minus deaths (i.e. population change disregarding migration). The small map shows the result on a regional level, and the big map shows changes on the municipal level. Red shades refer to population decrease, blue shades to population increase, and yellow shades to balanced development. The map shows that levels of natural population change do not only vary across but also within the Nordic countries. Urban areas such as Stockholm and Gothenburg in Sweden; Oslo and Bergen in Norway; Copenhagen and Aarhus in Denmark; as well as Helsinki and Turku in Finland all experienced positive natural population change. This can be attributed to the comparatively young population age structure of these urban centres. Young people of child-bearing age often cluster in cities for study and work, and many start families there. By contrast, rural and remote areas often have a higher proportion of older people and, as such, tend to register more deaths than births, resulting in negative natural population change. These patterns are particularly pronounced in Finland but also in the northern parts of Sweden and Norway. Nonetheless, there are exceptions. In Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands, which had comparatively high levels of natural population growth at national level, a majority of municipalities, including many in rural areas, still registered more births than deaths in 2022 (77% of municipalities in Iceland, 60% in Greenland, 67% on the Faroe Islands). In the other Nordic countries, only a minority of municipalities, mostly in urban centres, recorded natural population increase in 2022 (30% in Norway and Sweden, 26% in Denmark, 12% in Finland).

2025 April

- Demography

- Nordic Region

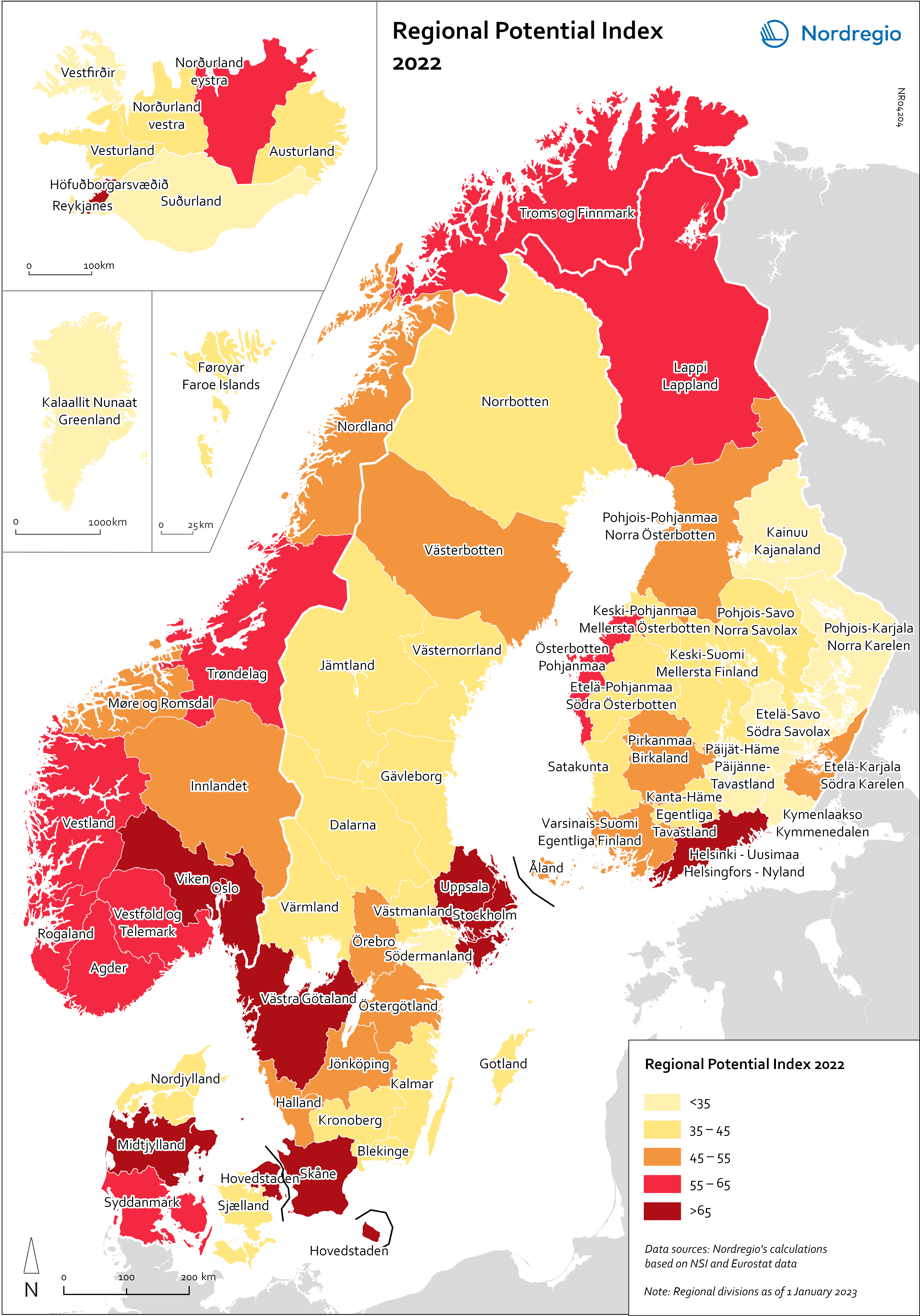

Regional Potential Index 2022

This map shows the result of Nordregio’s Regional Potential Index in 2024 (data from 2022). Nordregio’s Regional Potential Index (RPI) enables cross-regional comparison of development potential and illustrates the regional balance between the Nordic countries and has been part of the State of the Nordic Region report since 2018. The purpose of this multidimensional index is to summarise the current and past performance of the Nordic regions across major policy domains. The index helps to identify regions that have high potential and those in need of further support to boost their potential and meet existing challenges. It provides policy-makers with a comparative learning tool that informs the design of effective regional development strategies at Nordic level. Nordregio’s RPI is a multi-item measurement scale that incorporates information about the demographics, labour market and economic output of the Nordic countries’ 66 administrative regions. It consists of eight indicators classified into four main groups and eight subgroups. These components and indicators were originally selected on the basis of their relevance for regional development. The 2024 RPI is based on a new refined method that maintains a similar set of indicators but applies a more robust statistical process to the construction of the RPI. In brief, the new methodology consists of a pre-processing stage, in which the input data is prepared for analysis, and a processing stage, in which the indicators are weighted and aggregated. More information about the method can be found in the State of the Nordic Region 2024 report. The RPI was calculated retroactively for the 2015–2023 period. However, the focus in this section is on 2022 – the most recent year in our time series with full data coverage. The map shows the redesigned RPI for that period. In line with the principles of accumulation and agglomeration that drive the…

2025 April

- Demography

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

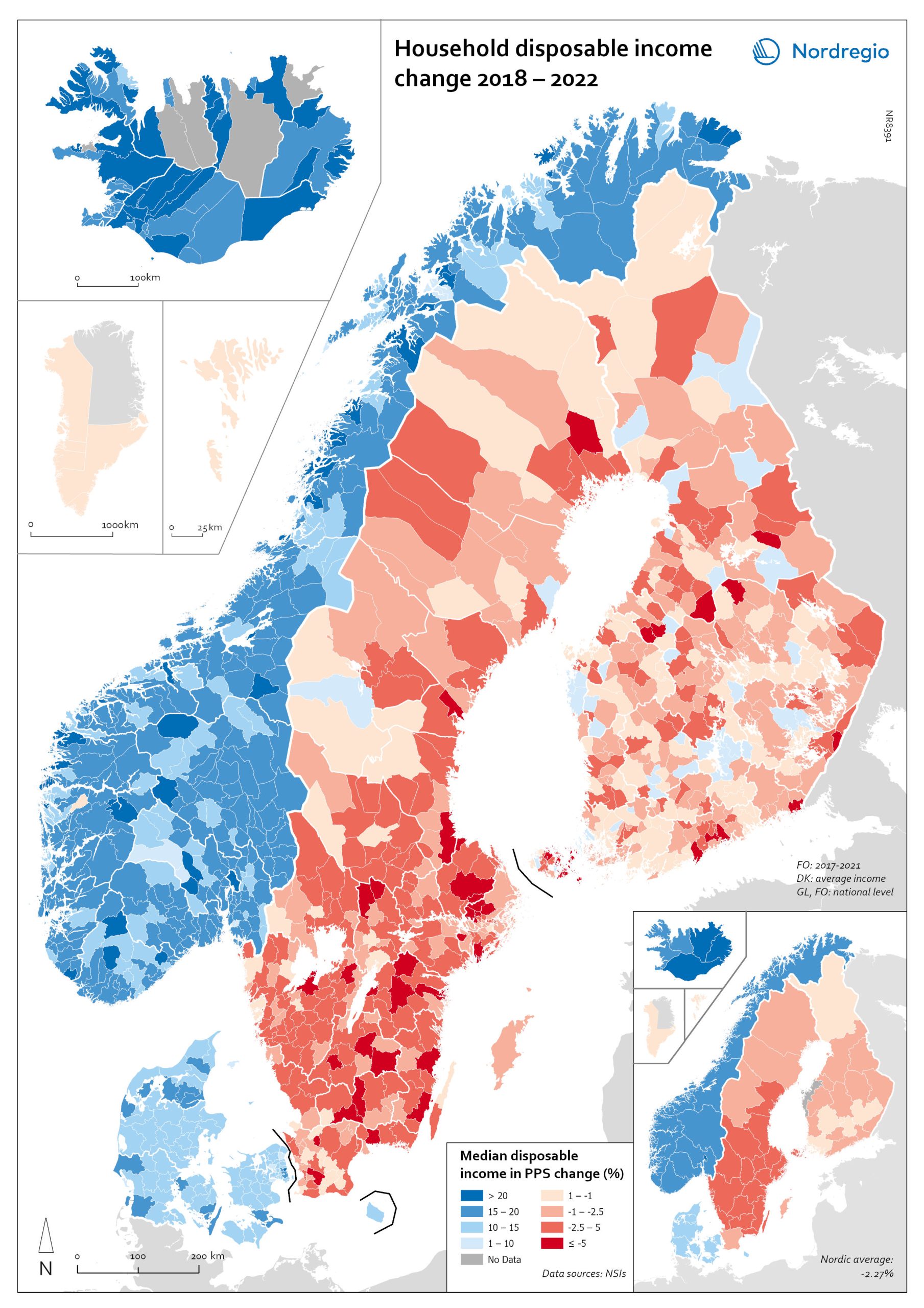

Household disposable income change 2018-2022

This map shows the percentage change in household disposable income between 2018 and 2022 in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map). Household disposable income per capita is a common indicator of the affluence of households and, therefore, of the material quality of life. It reflects the income generated by production, measured as GDP that remains in the regions and is financially available to households, excluding those parts of GDP retained by corporations and government. In sum, household disposable income is what households have available for spending and saving after taxes and transfers. It is ‘equivalised’ – adjusted for household size and composition – to enable comparison across all households. Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) is used to compare the countries’ economies and the cost of living for households. As shown in the map, between 2018 and 2022, household disposable income increased for all Danish, Icelandic, and Norwegian municipalities and decreased for Finnish and Swedish municipalities. On average, the city municipalities have higher incomes and increased most in Finland and Sweden in 2018–2022. In Sweden, a tendency towards larger falls in income was observed in several southern municipalities. In summary, absolute household income increased in all Nordic countries but not when measured in purchasing power. Based on this metric, on average, Norwegian households are the most well-off and Iceland the worst off, while Danish households benefited from a stronger currency in 2022. Single-parent households have had lower increases in household income than other families in Norway and parts of Sweden. Municipalities show a similar trend in Norway and Denmark, although Norwegian coastal municipalities fared slightly better in 2022. Disposable income is falling in all Swedish and Finnish municipalities.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

Household disposable income 2022

This map shows the median household disposiable income measured in purchasing power standard (PPS) in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map) in 2022. Household disposable income per capita is a common indicator of the affluence of households and, therefore, of the material quality of life. It reflects the income generated by production, measured as GDP that remains in the regions and is financially available to households, excluding those parts of GDP retained by corporations and government. In sum, household disposable income is what households have available for spending and saving after taxes and transfers. It is ‘equivalised’ – adjusted for household size and composition – to enable comparison across all households. Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) is used to compare the countries’ economies and the cost of living for households. The map shows the intra-municipal differences in household disposable income in PPS, which reveals the different patterns in the Nordic countries. Norwegian coastal municipalities have slightly higher household disposable income than inland municipalities, with some exceptions. Finnish, Icelandic, and Swedish municipalities generally have much lower household disposable income compared to Norwegian and Danish municipalities, except for the larger urban areas. In Denmark, most municipalities are at a similarly high level, except for remote islands in the south. The differences between the Icelandic municipalities are rather small, at a medium to lower level.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

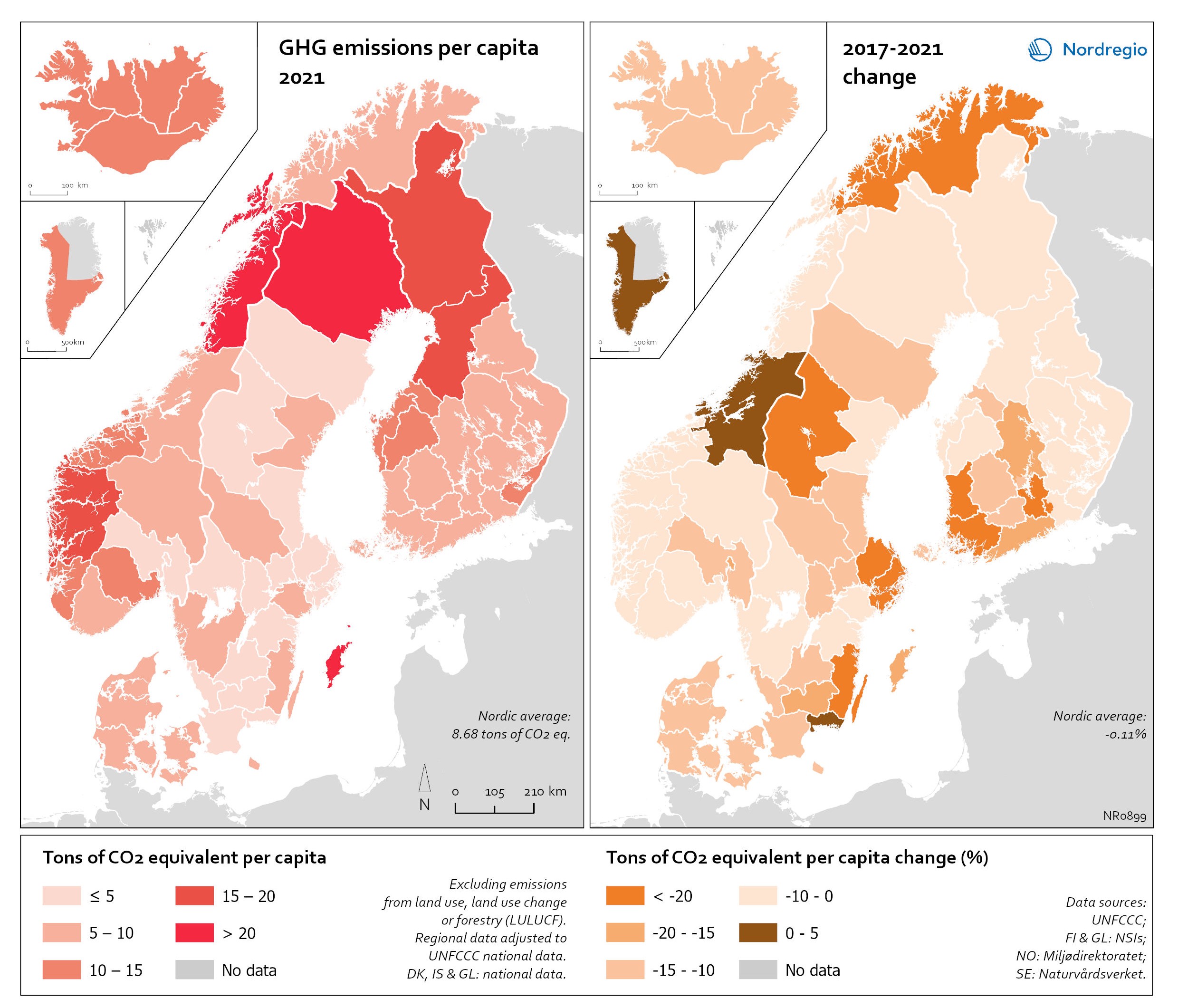

Regional GHG emissions per capita in 2021 and change 2017-2021 on a territorial basis

The data excludes emissions from land use, land use change or forestry (LULUCF). The regional data has been adjusted to UNFCCC national data. The data for Denmark, Iceland and Greenland is on national level. It should be noted that displaying emissions on a territorial basis may be skewed due to the inter-regional dynamics of energy processes, natural resource distributions and concentrations of industrial activities. From 2017 to 2021, the Nordic regions cut their per-capita GHG emissions by on average 11.3%, with an overall Nordic average fall of 8.7% over the same period. In regions historically reliant on fossil fuels for heat and power generation, emissions have continued to decline. This trend is evident in Denmark, as well as in Southern Sweden and Southern Finland – densely populated areas that have taken steps toward expanding district heating coverage and reducing carbon intensity. The largest decrease in GHG emissions per capita was found in Troms and Finnmark, with a 42.3% decrease, Satakunta with a 30.2% decrease and Päijät-Häme – Päijänne-Tavastland with a 29.2% decrease. Only three regions (Greenland, Trøndelag and Blekinge) saw an increase in GHG emissions per capita. At an aggregated level, industrial-related emissions decreased throughout the Nordic Region, but this trend does not hold true for regions in Norway with intensive offshore oil and gas operations. For instance, Nordland, Vestland, Møre og Romsdal, Vestfold and Telemark exhibited the highest per capita emissions in 2021. Between 2017 and 2021, emissions were increasing in many Norwegian regions with intensive offshore oil and gas activity, but also in Norrbotten in Sweden (21.2 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per capita) and Gotland (33.6 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per capita) due to intensive activity in the metal and cement industries, respectively, as well as in several Finnish regions. At the other end of the scale, the…

2025 April

- Environment

- Nordic Region

Gender distribution in employment 2021

This maps shows the gender distribution in employment at both municipal (big map) and regional levels (small map) in the Nordic Region in 2021 (measured in November). Blue shades indicate more men employed and red shades more women. Most regions had higher employment rates for men than women, with an average of 3.7% more men across the countries and sectors. In Finland, the rates were more balanced, with only 1.3% more men in employment. In three regions in Finland, employment rates were slightly higher for women: Etelä-Karjala – Södra Karelen, with 0.8% more women than men; Kainuu – Kajanaland, with 0.4%; and Uusimaa – Nyland with 0.1%. These are the only regions in the Nordic countries with a prevalence of employed women at the regional level. For the rest, employment rates were higher for men, with Icelandic regions having the largest share: Suðurnes had 11.3% more men than women, Vesturland 8.8%, Austurland 8.7%, and Suðurland 8.2%. The average for the Icelandic regions was 7.5%. For Denmark, this was 4.9%, for Sweden, 3.9%, and for Norway, 3.4%. At the municipal level, however, the situation was much more varied. Åland is one of the most extreme examples. Although the average was 2.5% more men employed than women, Åland has several municipalities with extremes at both ends. On the one hand, there are municipalities like Lumparland, with 16% more women than men, and Brändö, with 11.3%. On the other hand, Kökar had 64% more men than women. The variations between Ålandic municipalities can largely be attributed to the municipalities’ population size. The larger cities, like Trøndelag in Norway, may be more balanced at the regional level, but within the region, there are municipalities with a 20% prevalence of women in employment (Namsskogan, Meråker, Holtålen), as well as some with 18% (or higher) more…

2025 April

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

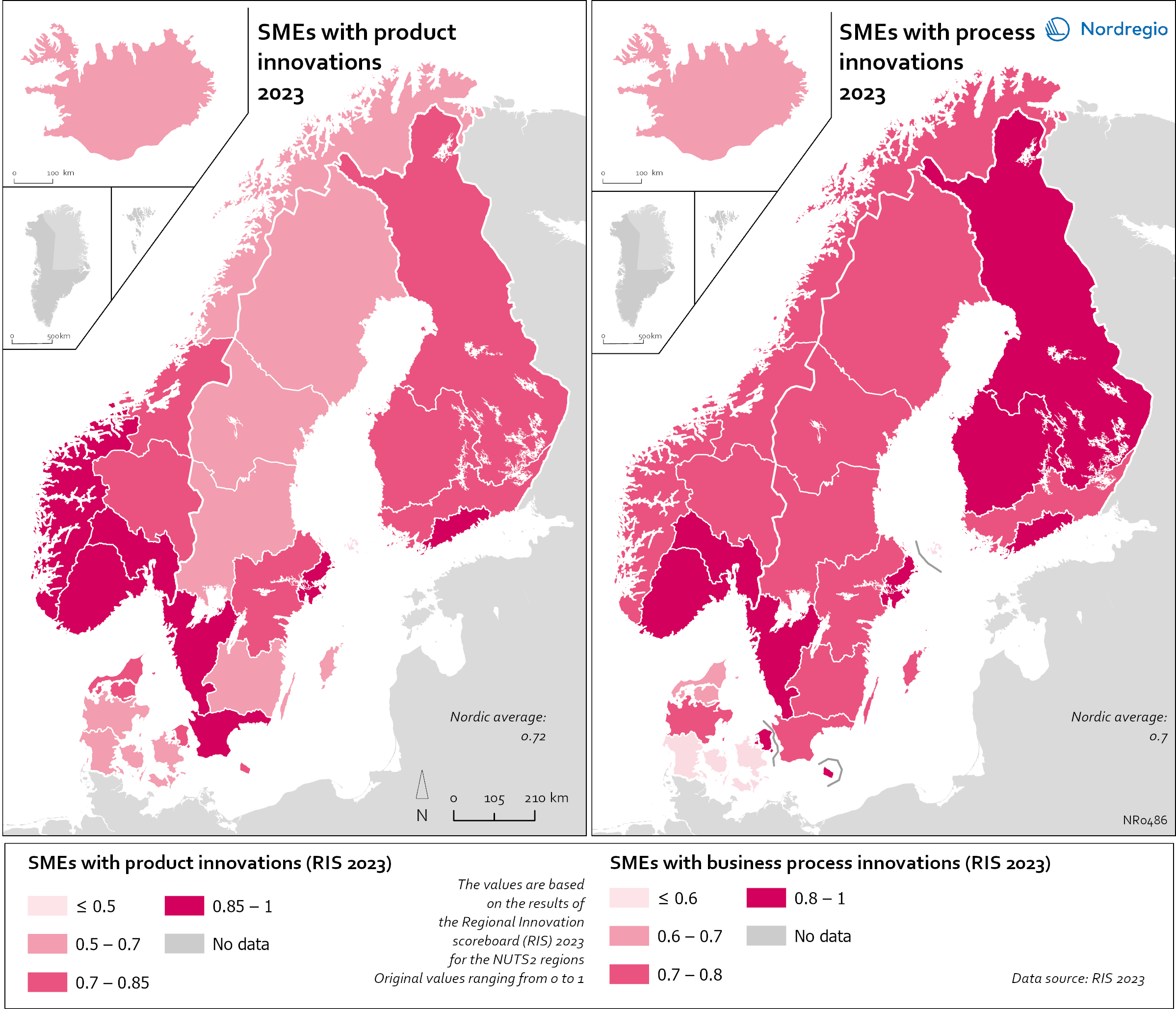

Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) with product and business process innovation in 2023

These maps depicts Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) with product innovation (left map) and process innovation (right map) in 2023. The data is displayed at the NUTS2 level and the data comes from the Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023. The left map depicts SMEs introducing product innovations as a percentage of SMEs in the Nordic regions, calculated as the share of SMEs who introduced at least one product innovation. The values for the map are normalised from 0–10. In this context, a product innovation is defined as the market introduction of a good or service that is new or significantly improved with respect to its capabilities, user-friendliness, components, or sub-systems. Rural regions tend to have lower levels of SMEs with product innovations, while urban regions have the highest levels. In 2023, Åland (0.235) had the lowest number of SMEs with product innovations in the Nordic Region, while Oslo had the highest (1.0). Etelä-Suomi and Stockholm regions were slightly behind, with 0.954 and 0.948, respectively. In Denmark, the leading regions were the Capital Region (Hovedstaden) and Northern Jutland (Nordjylland), with 0.719 and 0.715, respectively. Southern Denmark (Syddanmark) had the lowest level in Denmark, at 0.545. In Norway, the lowest value was in Northern Norway (Nord-Norge), 0.67, while in Sweden it was Middle Norrland (Mellersta Norrland), with 0.53. Taken as an average across the Nordic countries, Norway has a significantly higher number of SMEs with product innovations than the other countries. The right map shows the share of SMEs introducing at least one business-process innovation, which includes process, marketing, and organisational innovations. In general, Nordic SMEs are more likely to innovate in products rather than processes. The highest shares of process-innovating SMEs are found in most of the Finnish regions ranging from 0,79 in Länsi-Suomi to 0,91 in Etelä-Suomi, except of Åland…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

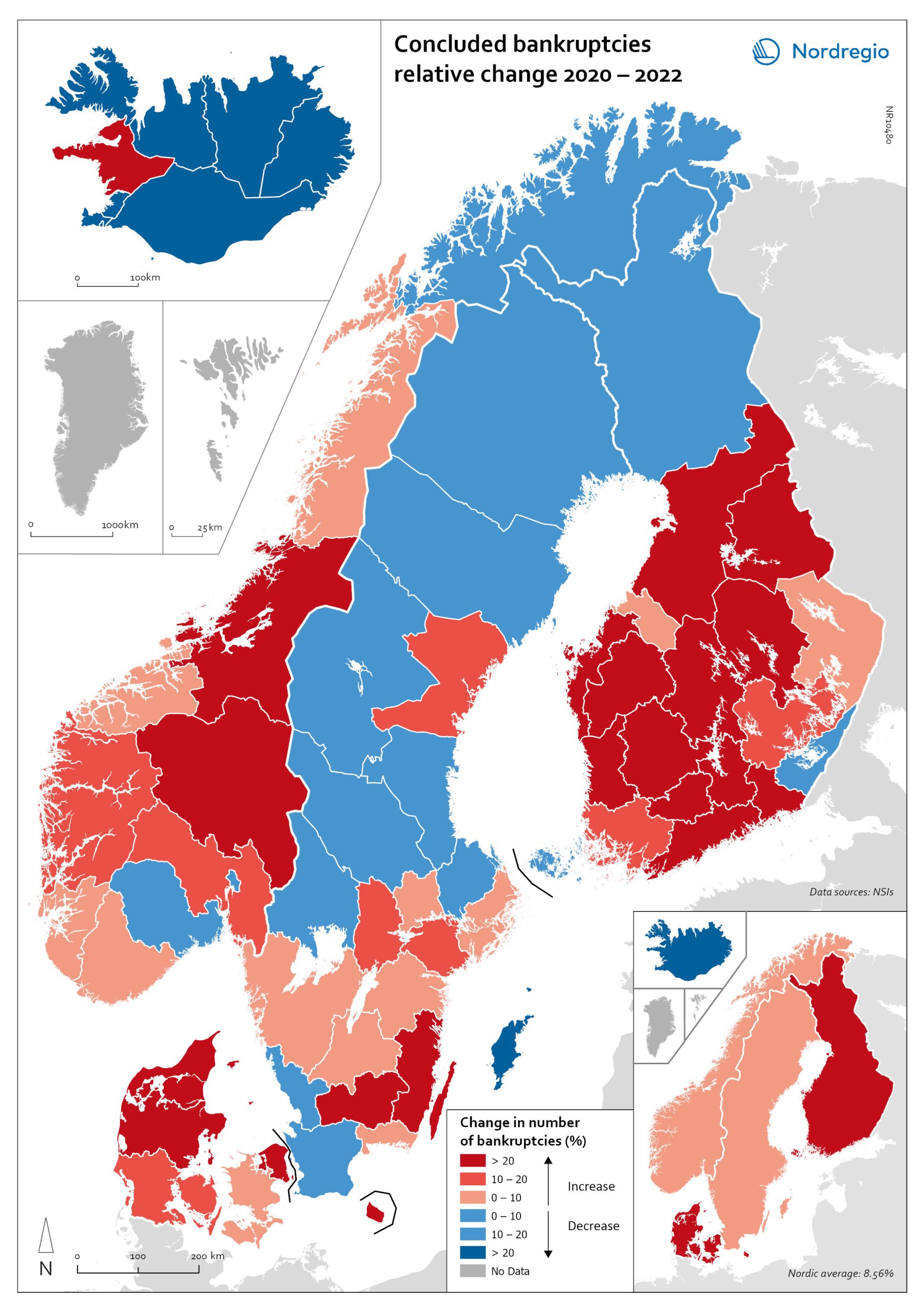

Change in the number of business bankruptcies (2020–2022)

This map depicts the change in total number of bankruptcies in the Nordic regions between 2020 and 2022. The red shades indicates an increase in numbers of bunkruptcies and blue shades a decrease. The big map shows the regional level and the small map the national level. The rate of business bankruptcies is a core indicator of the robustness of the economy from the business perspective. Nordic and international businesses have been impacted by both the COVID-19 pandemic and rising inflation in recent years. In terms of the level of bankruptcies, data from Eurostat (2024) shows that the Nordic countries fared relatively well compared to other high-income countries between 2020 – 2022. In the years during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the most densely populated regions saw the highest levels of bankruptcies. This finding is partly to be expected, as these regions also tend to be those with the highest number of companies. However, some variation can be seen across the countries. Overall, Iceland and Finland experienced the lowest rate of bankruptcies in 2020 and 2022. Denmark had the highest level of bankruptcies during COVID-19. Potential explanations for the national variations may include the countries’ varying strategic approaches to the pandemic. Denmark enforced more restrictive lockdowns compared to, for example, Sweden, where the less restrictive approach has been linked to the more limited impact on business bankruptcies in the early part of the pandemic. Furthermore, there is a large consensus that the many jobretention schemes across the Nordic Region also served to limit the number of bankruptcies. However, new data from early 2024 shows that after the job-retention schemes ended, and while high inflation and interest rates were increasing the pressure on Nordic companies, the level of bankruptcies increased. In 2023, 8,868 companies went bankrupt in Sweden the highest number…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

Gini coefficient change 2018-2022

This map shows the percentage change in the Gini coefficient between 2018 and 2022. The big map shows the change on municipal level and the big map at regional level. Blue shades indicate a decrease in income inequality, while red areas indicate an increase in income inequality The Gini coefficient index is one of the most widely used inequality measures. The index ranges from 0–1, where 0 indicates a society where everyone receives the same income, and 1 is the highest level of inequality, where one individual or group possesses all the resources in the society, and the rest of the population has nothing. The map illustrates significant variations in the change in income inequality across Nordic municipalities and regions. Between 2018 and 2022, income inequality increased in predominantly rural municipalities, notably in Jämtland, Gävleborg, Dalarna and Västerbotten in Sweden, as well as Telemark in Norway. For Denmark, the rise in inequality is mainly for the municipalities in Western Jutland. At the same time, approximately one third of municipalities in the Nordic Region experienced a decrease in income inequality during the same period, primarily in Finland and Åland. For example, in Finland, the distribution of inequality was more varied. This trend aligns with the ongoing narrowing of the household income gap observed in many Finnish municipalities since 2011, which is mainly attributed to the economic downturn of the early 2010s, as well as demographic shifts such as outmigration and ageing.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

Gini coefficient for disposable income in 2022

This map shows the Gini coefficient in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map) in 2022 (no data was available for Iceland). Blue shades indicate a Gini coefficient below the Nordic average. Red areas indicate a Gini coefficient above the Nordic average (0.27, excluding Greenland, as a statistical outlier). The data for the Faroe Islands is for 2021. The Gini coefficient index is one of the most widely used inequality measures. The index ranges from 0–1, where 0 indicates a society where everyone receives the same income, and 1 is the highest level of inequality, where one individual or group possesses all the resources in the society, and the rest of the population has nothing. In 2022, the highest municipality income disparities were observed in the capital city regions of Denmark, Finland and Sweden, each of which had Gini coefficients around 0.6. Danderyd (0.64), Lidingö (0.52), and Gentofte (0.51) had the highest Gini coefficients. These municipalities also have some of the highest incomes in their respective countries.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

R&D and non-R&D expenditures in the public and private sector

These maps shows the expenditure on Research and Development (R&D) in the public and business sectors as a percentage of regional GDP, along with non-R&D innovation expenditure in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as a percentage of turnover. Together, these metrics offer a comprehensive understanding of the innovation landscape and provide insights into governments’ and higher education institutions’ commitment to foundational research, as well as the competitiveness and dynamism of the business environment and SMEs’ innovation capacity. By considering investment in both R&D and non-R&D activities, these indicators illustrate a broad spectrum of innovation drivers, from basic research to market-driven initiatives, and underscore the diverse pathways through which innovation fosters economic growth and social progress First, the top left map showcases R&D expenditure in the public sector as a percentage of GDP in the Nordic countries in 2023. In that year, the European level of R&D expenditure in the public sector, as a percentage of GDP, was 0.78%. By comparison, the Nordic average was 0.9%. While the more urban regions, in general, lead the Nordic regions, this is not always the case, as shown by the variation between the frontrunners. The leading region is Trøndelag (including Norway’s third-largest city, Trondheim), with 2.30% of regional GDP. It is in third place in the EU as a whole. The next regions are Övre Norrland with 1.77%, Northern Jutland with 1.54%, Östra Mellansverige with 1.52%, and Hovedstaden with 1.49%. A common feature of most of the top-ranking regions is that they host universities and other higher education institutions known for innovation practices. Most Nordic regions have not seen significant increases or decreases in public R&D spending between 2016 and 2023. The top right map focuses on the private sector’s investment in research and development activities and depicts R&D expenditure in the business sector…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

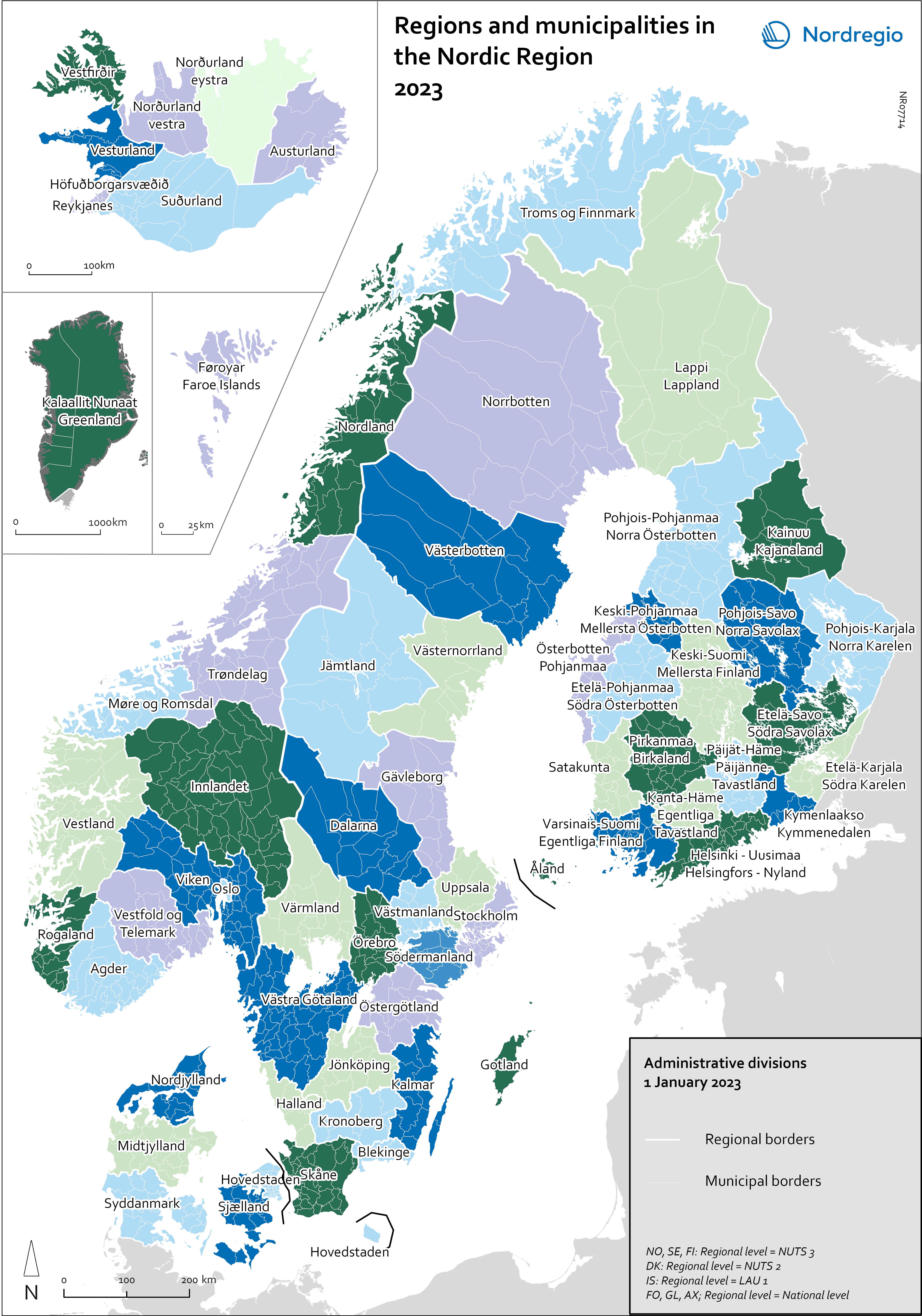

Regions and municipalities in the Nordic Region 2023

This map shows the municipal and regional borders of the Nordic Region as of 1 January 2023*, the names refer to the regions. The Nordic Region is vast and has a diverse physical geography, stretching from the northern edge of the European mainland to north of the Arctic Circle. It consists of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, as well as the three self-governing regions, the Faroe Islands and Greenland (both part of the Kingdom of Denmark) and Åland (part of the Republic of Finland). This map shows the municipal and regional borders of the Nordic Region as of 1 January 2023*, the names refer to the regions. The Nordic Region is vast and has a diverse physical geography, stretching from the northern edge of the European mainland to north of the Arctic Circle. It consists of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, as well as the three self-governing regions, the Faroe Islands and Greenland (both part of the Kingdom of Denmark) and Åland (part of the Republic of Finland). The table below summarises the administrative structure in each of the Nordic countries. These structures form the basis for the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) classification, a hierarchical system dividing European states into statistical units for research purposes. In general, the NUTS and Local Administrative Units (LAU) classifications follow existing divisions, but this may differ from country to country. Light grey frames represent the regional level presented In Nordregio’s map. As of 1 Jan 2023, there were 66 regions at this level. Dark grey frames show the local units represented in most of the municipal maps. As of 1 Jan 2023 there were 1,133 units at this level. *There are usually some changes in the administrative borders every year. Since 2023 there have for example been changes in…

2025 April

- Nordic Region