122 Maps

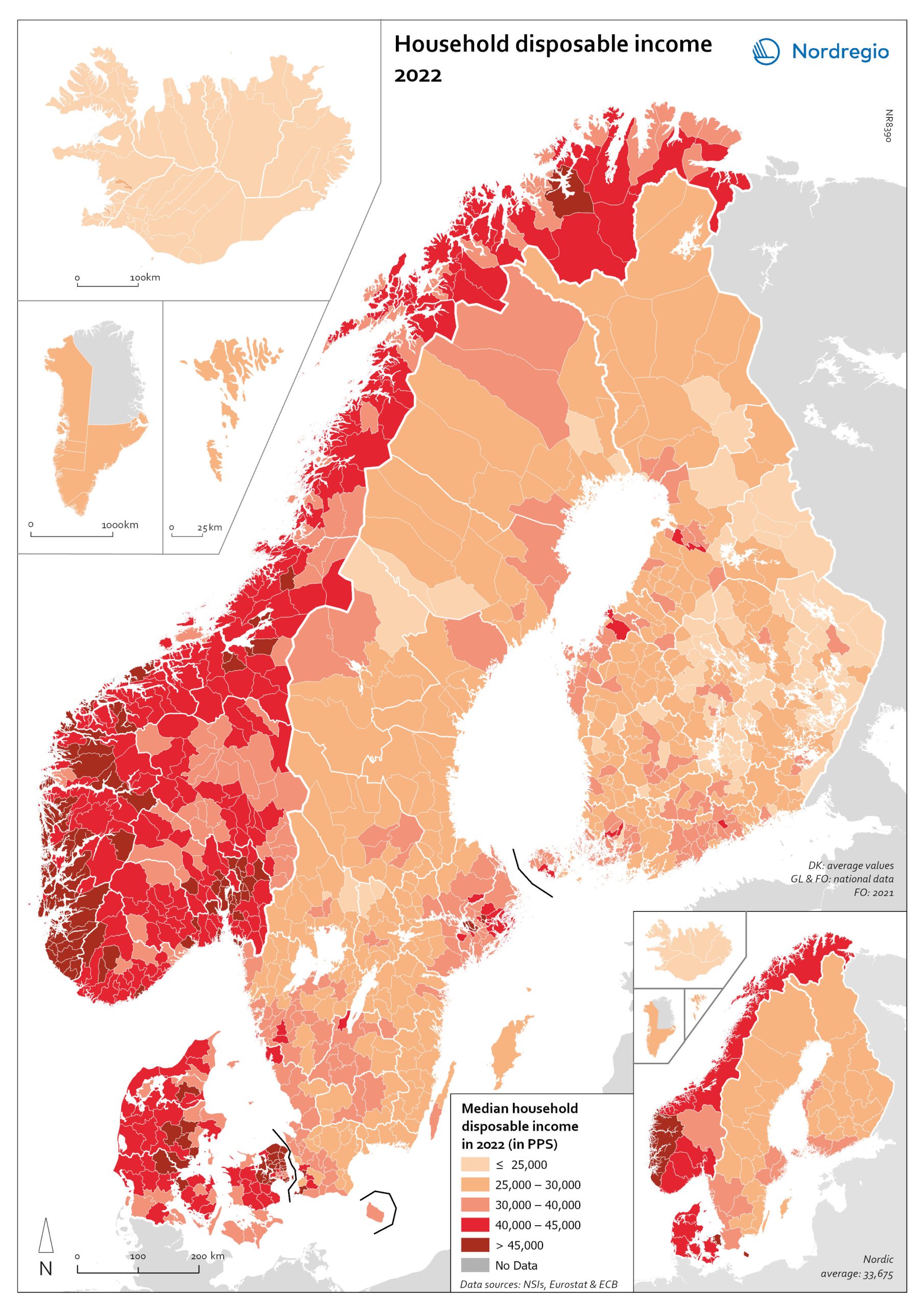

Household disposable income 2022

This map shows the median household disposiable income measured in purchasing power standard (PPS) in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map) in 2022. Household disposable income per capita is a common indicator of the affluence of households and, therefore, of the material quality of life. It reflects the income generated by production, measured as GDP that remains in the regions and is financially available to households, excluding those parts of GDP retained by corporations and government. In sum, household disposable income is what households have available for spending and saving after taxes and transfers. It is ‘equivalised’ – adjusted for household size and composition – to enable comparison across all households. Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) is used to compare the countries’ economies and the cost of living for households. The map shows the intra-municipal differences in household disposable income in PPS, which reveals the different patterns in the Nordic countries. Norwegian coastal municipalities have slightly higher household disposable income than inland municipalities, with some exceptions. Finnish, Icelandic, and Swedish municipalities generally have much lower household disposable income compared to Norwegian and Danish municipalities, except for the larger urban areas. In Denmark, most municipalities are at a similarly high level, except for remote islands in the south. The differences between the Icelandic municipalities are rather small, at a medium to lower level.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

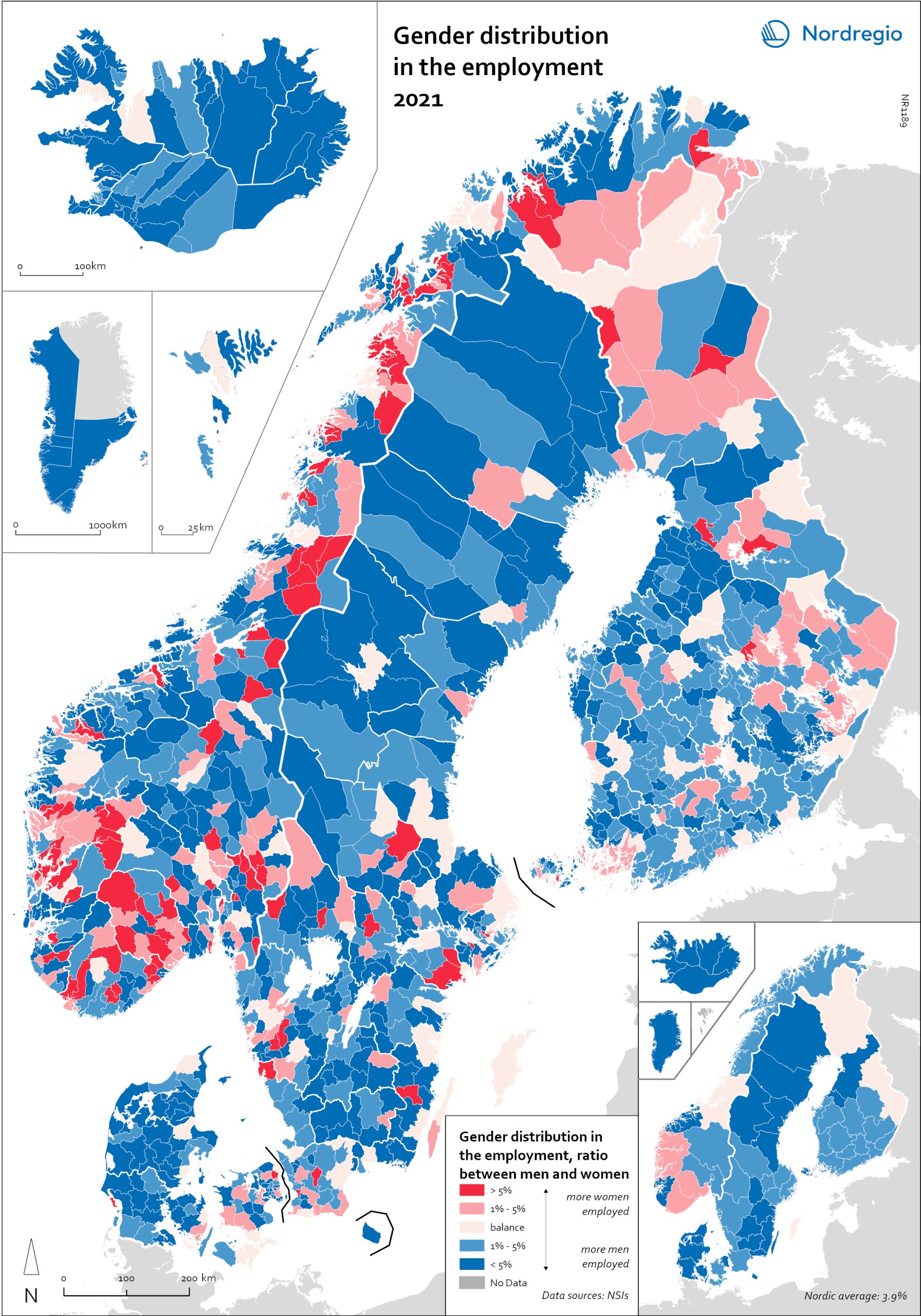

Gender distribution in employment 2021

This maps shows the gender distribution in employment at both municipal (big map) and regional levels (small map) in the Nordic Region in 2021 (measured in November). Blue shades indicate more men employed and red shades more women. Most regions had higher employment rates for men than women, with an average of 3.7% more men across the countries and sectors. In Finland, the rates were more balanced, with only 1.3% more men in employment. In three regions in Finland, employment rates were slightly higher for women: Etelä-Karjala – Södra Karelen, with 0.8% more women than men; Kainuu – Kajanaland, with 0.4%; and Uusimaa – Nyland with 0.1%. These are the only regions in the Nordic countries with a prevalence of employed women at the regional level. For the rest, employment rates were higher for men, with Icelandic regions having the largest share: Suðurnes had 11.3% more men than women, Vesturland 8.8%, Austurland 8.7%, and Suðurland 8.2%. The average for the Icelandic regions was 7.5%. For Denmark, this was 4.9%, for Sweden, 3.9%, and for Norway, 3.4%. At the municipal level, however, the situation was much more varied. Åland is one of the most extreme examples. Although the average was 2.5% more men employed than women, Åland has several municipalities with extremes at both ends. On the one hand, there are municipalities like Lumparland, with 16% more women than men, and Brändö, with 11.3%. On the other hand, Kökar had 64% more men than women. The variations between Ålandic municipalities can largely be attributed to the municipalities’ population size. The larger cities, like Trøndelag in Norway, may be more balanced at the regional level, but within the region, there are municipalities with a 20% prevalence of women in employment (Namsskogan, Meråker, Holtålen), as well as some with 18% (or higher) more…

2025 April

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

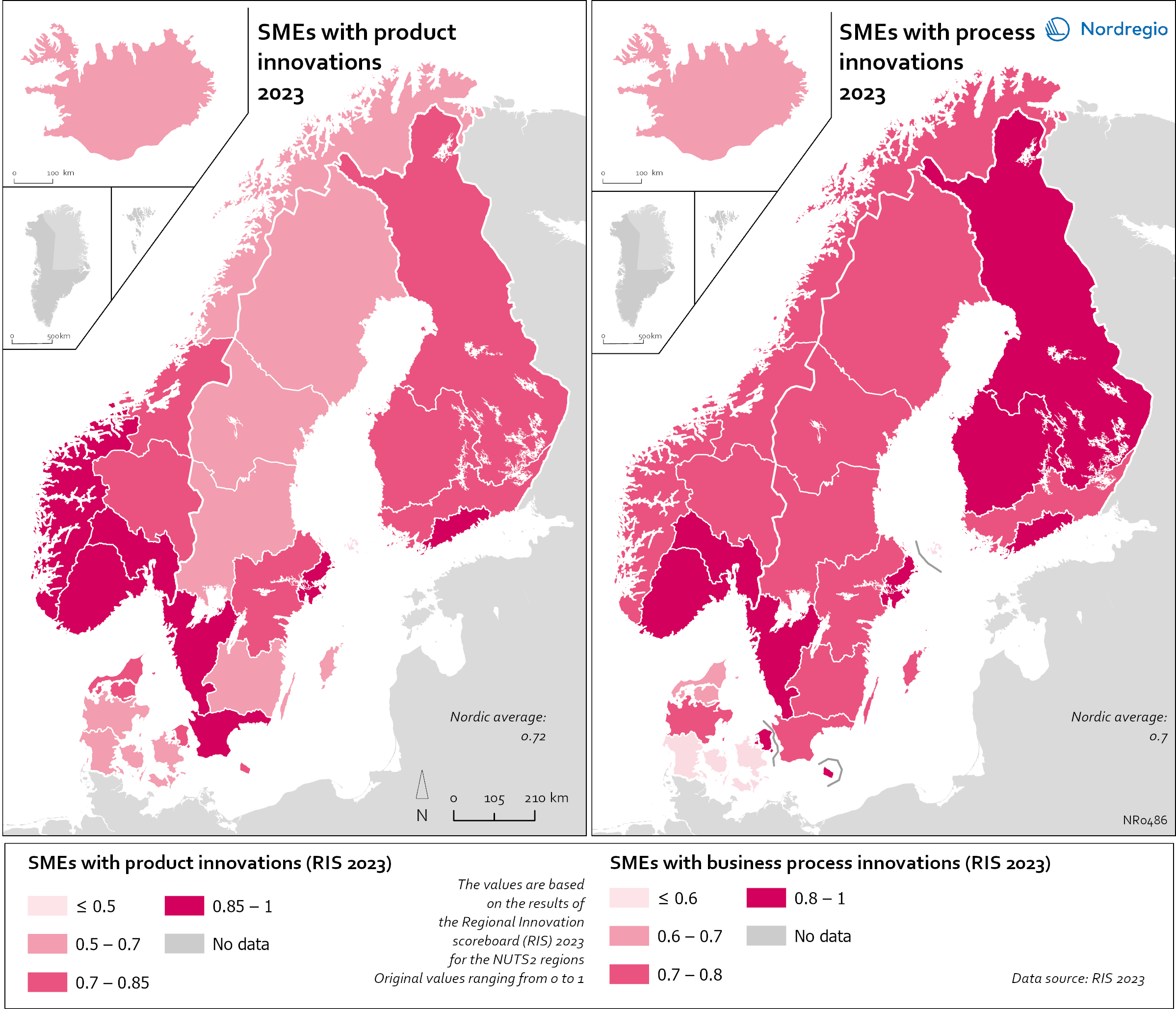

Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) with product and business process innovation in 2023

These maps depicts Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) with product innovation (left map) and process innovation (right map) in 2023. The data is displayed at the NUTS2 level and the data comes from the Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023. The left map depicts SMEs introducing product innovations as a percentage of SMEs in the Nordic regions, calculated as the share of SMEs who introduced at least one product innovation. The values for the map are normalised from 0–10. In this context, a product innovation is defined as the market introduction of a good or service that is new or significantly improved with respect to its capabilities, user-friendliness, components, or sub-systems. Rural regions tend to have lower levels of SMEs with product innovations, while urban regions have the highest levels. In 2023, Åland (0.235) had the lowest number of SMEs with product innovations in the Nordic Region, while Oslo had the highest (1.0). Etelä-Suomi and Stockholm regions were slightly behind, with 0.954 and 0.948, respectively. In Denmark, the leading regions were the Capital Region (Hovedstaden) and Northern Jutland (Nordjylland), with 0.719 and 0.715, respectively. Southern Denmark (Syddanmark) had the lowest level in Denmark, at 0.545. In Norway, the lowest value was in Northern Norway (Nord-Norge), 0.67, while in Sweden it was Middle Norrland (Mellersta Norrland), with 0.53. Taken as an average across the Nordic countries, Norway has a significantly higher number of SMEs with product innovations than the other countries. The right map shows the share of SMEs introducing at least one business-process innovation, which includes process, marketing, and organisational innovations. In general, Nordic SMEs are more likely to innovate in products rather than processes. The highest shares of process-innovating SMEs are found in most of the Finnish regions ranging from 0,79 in Länsi-Suomi to 0,91 in Etelä-Suomi, except of Åland…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

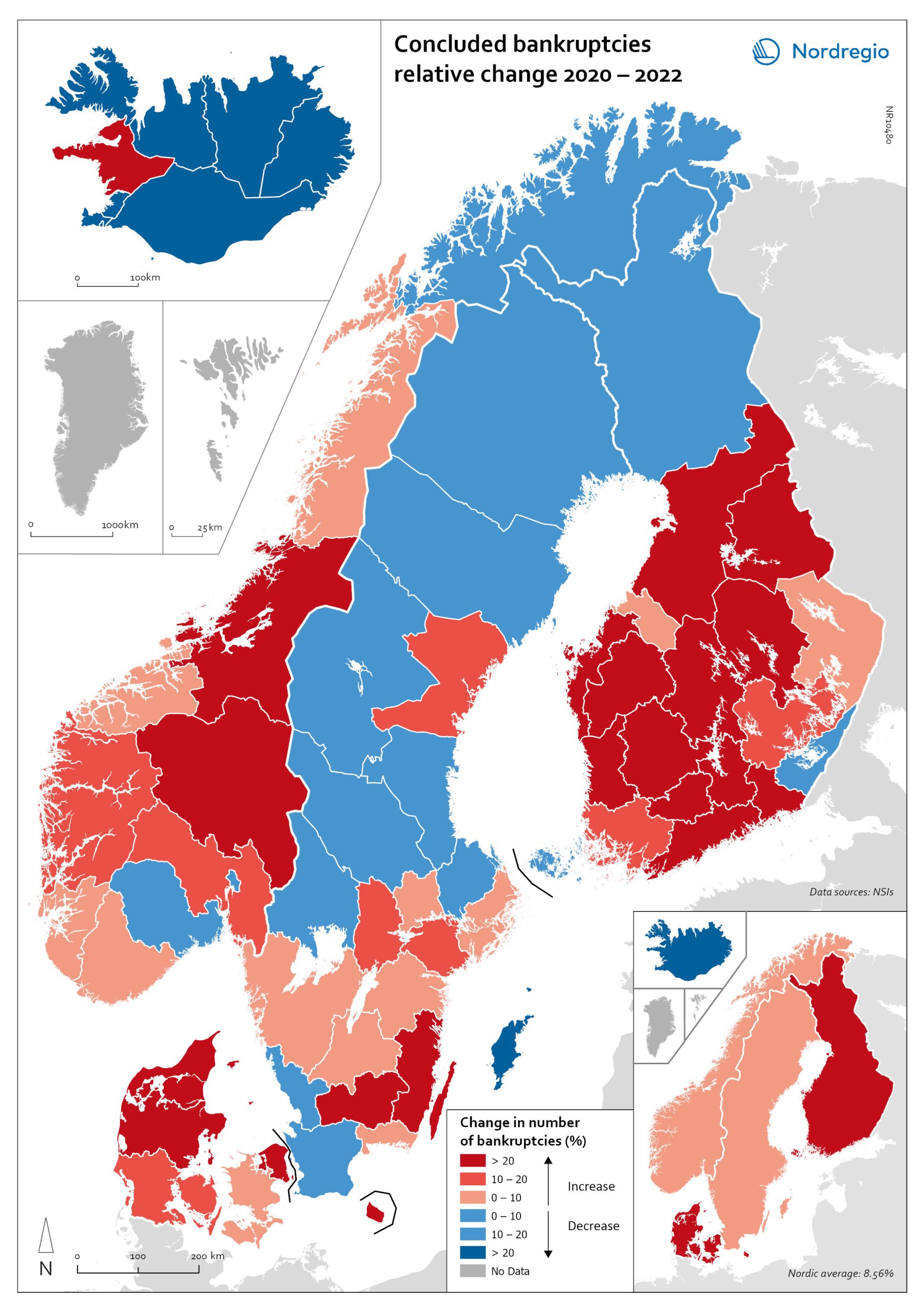

Change in the number of business bankruptcies (2020–2022)

This map depicts the change in total number of bankruptcies in the Nordic regions between 2020 and 2022. The red shades indicates an increase in numbers of bunkruptcies and blue shades a decrease. The big map shows the regional level and the small map the national level. The rate of business bankruptcies is a core indicator of the robustness of the economy from the business perspective. Nordic and international businesses have been impacted by both the COVID-19 pandemic and rising inflation in recent years. In terms of the level of bankruptcies, data from Eurostat (2024) shows that the Nordic countries fared relatively well compared to other high-income countries between 2020 – 2022. In the years during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the most densely populated regions saw the highest levels of bankruptcies. This finding is partly to be expected, as these regions also tend to be those with the highest number of companies. However, some variation can be seen across the countries. Overall, Iceland and Finland experienced the lowest rate of bankruptcies in 2020 and 2022. Denmark had the highest level of bankruptcies during COVID-19. Potential explanations for the national variations may include the countries’ varying strategic approaches to the pandemic. Denmark enforced more restrictive lockdowns compared to, for example, Sweden, where the less restrictive approach has been linked to the more limited impact on business bankruptcies in the early part of the pandemic. Furthermore, there is a large consensus that the many jobretention schemes across the Nordic Region also served to limit the number of bankruptcies. However, new data from early 2024 shows that after the job-retention schemes ended, and while high inflation and interest rates were increasing the pressure on Nordic companies, the level of bankruptcies increased. In 2023, 8,868 companies went bankrupt in Sweden the highest number…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

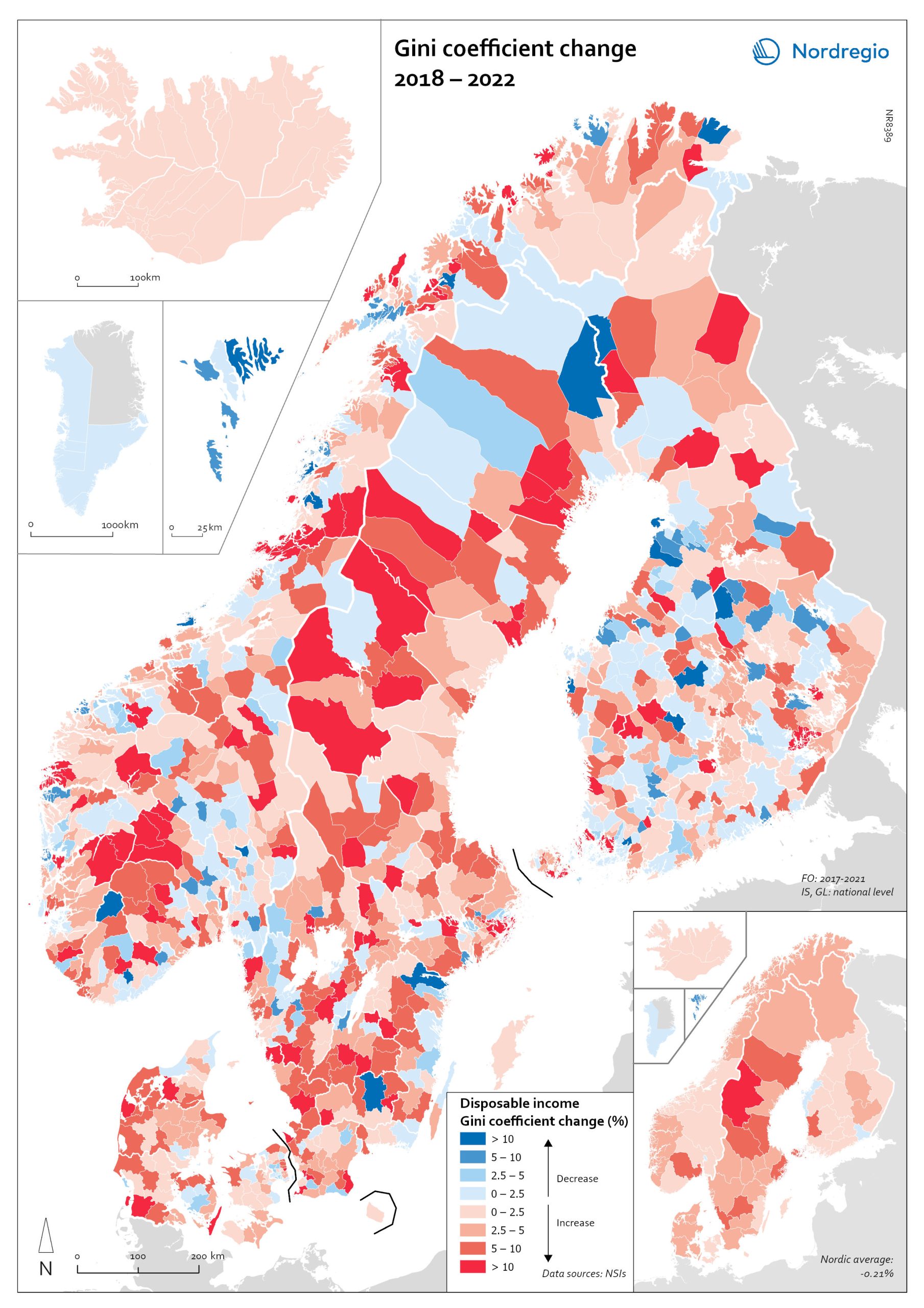

Gini coefficient change 2018-2022

This map shows the percentage change in the Gini coefficient between 2018 and 2022. The big map shows the change on municipal level and the big map at regional level. Blue shades indicate a decrease in income inequality, while red areas indicate an increase in income inequality The Gini coefficient index is one of the most widely used inequality measures. The index ranges from 0–1, where 0 indicates a society where everyone receives the same income, and 1 is the highest level of inequality, where one individual or group possesses all the resources in the society, and the rest of the population has nothing. The map illustrates significant variations in the change in income inequality across Nordic municipalities and regions. Between 2018 and 2022, income inequality increased in predominantly rural municipalities, notably in Jämtland, Gävleborg, Dalarna and Västerbotten in Sweden, as well as Telemark in Norway. For Denmark, the rise in inequality is mainly for the municipalities in Western Jutland. At the same time, approximately one third of municipalities in the Nordic Region experienced a decrease in income inequality during the same period, primarily in Finland and Åland. For example, in Finland, the distribution of inequality was more varied. This trend aligns with the ongoing narrowing of the household income gap observed in many Finnish municipalities since 2011, which is mainly attributed to the economic downturn of the early 2010s, as well as demographic shifts such as outmigration and ageing.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

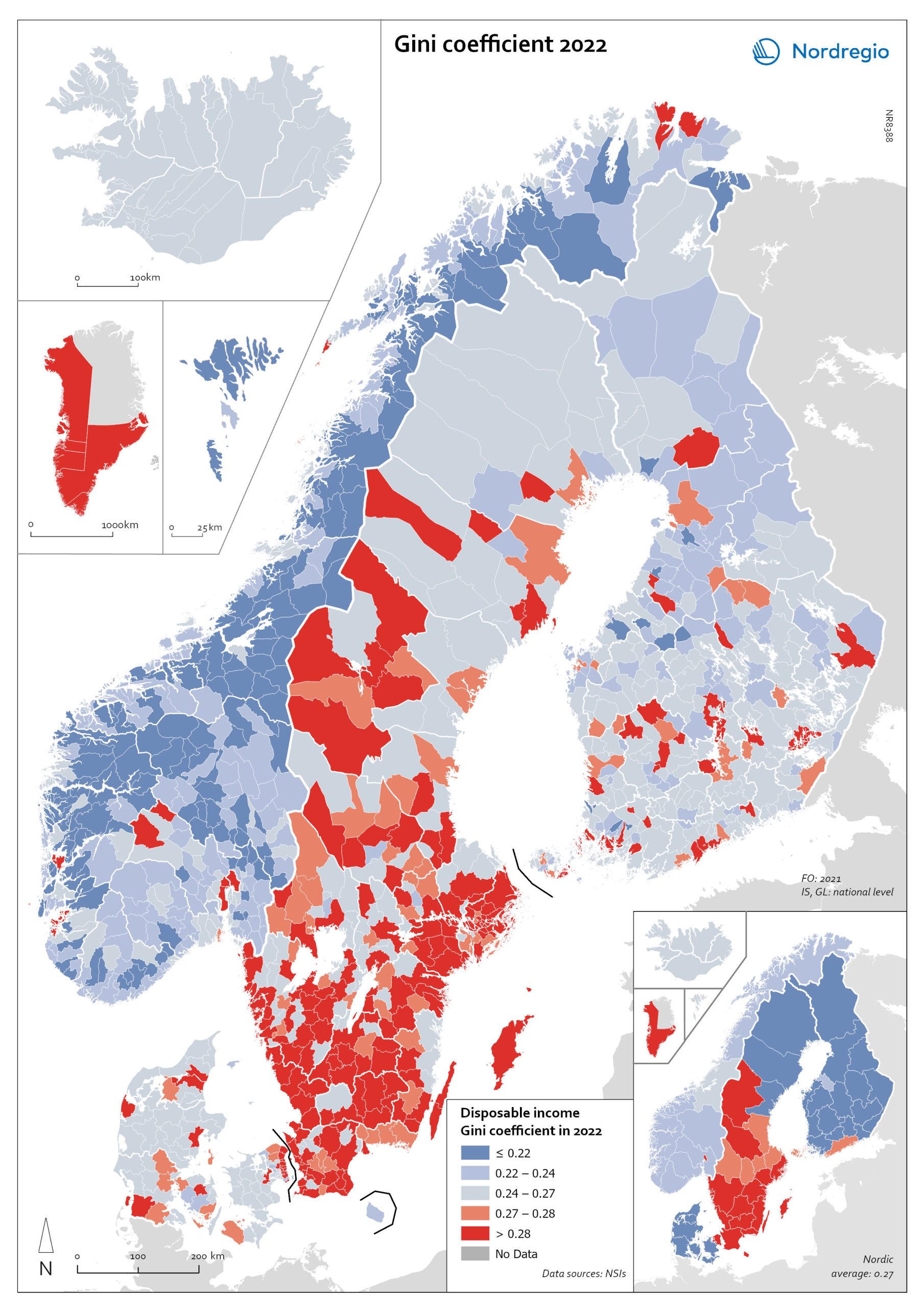

Gini coefficient for disposable income in 2022

This map shows the Gini coefficient in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map) in 2022 (no data was available for Iceland). Blue shades indicate a Gini coefficient below the Nordic average. Red areas indicate a Gini coefficient above the Nordic average (0.27, excluding Greenland, as a statistical outlier). The data for the Faroe Islands is for 2021. The Gini coefficient index is one of the most widely used inequality measures. The index ranges from 0–1, where 0 indicates a society where everyone receives the same income, and 1 is the highest level of inequality, where one individual or group possesses all the resources in the society, and the rest of the population has nothing. In 2022, the highest municipality income disparities were observed in the capital city regions of Denmark, Finland and Sweden, each of which had Gini coefficients around 0.6. Danderyd (0.64), Lidingö (0.52), and Gentofte (0.51) had the highest Gini coefficients. These municipalities also have some of the highest incomes in their respective countries.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

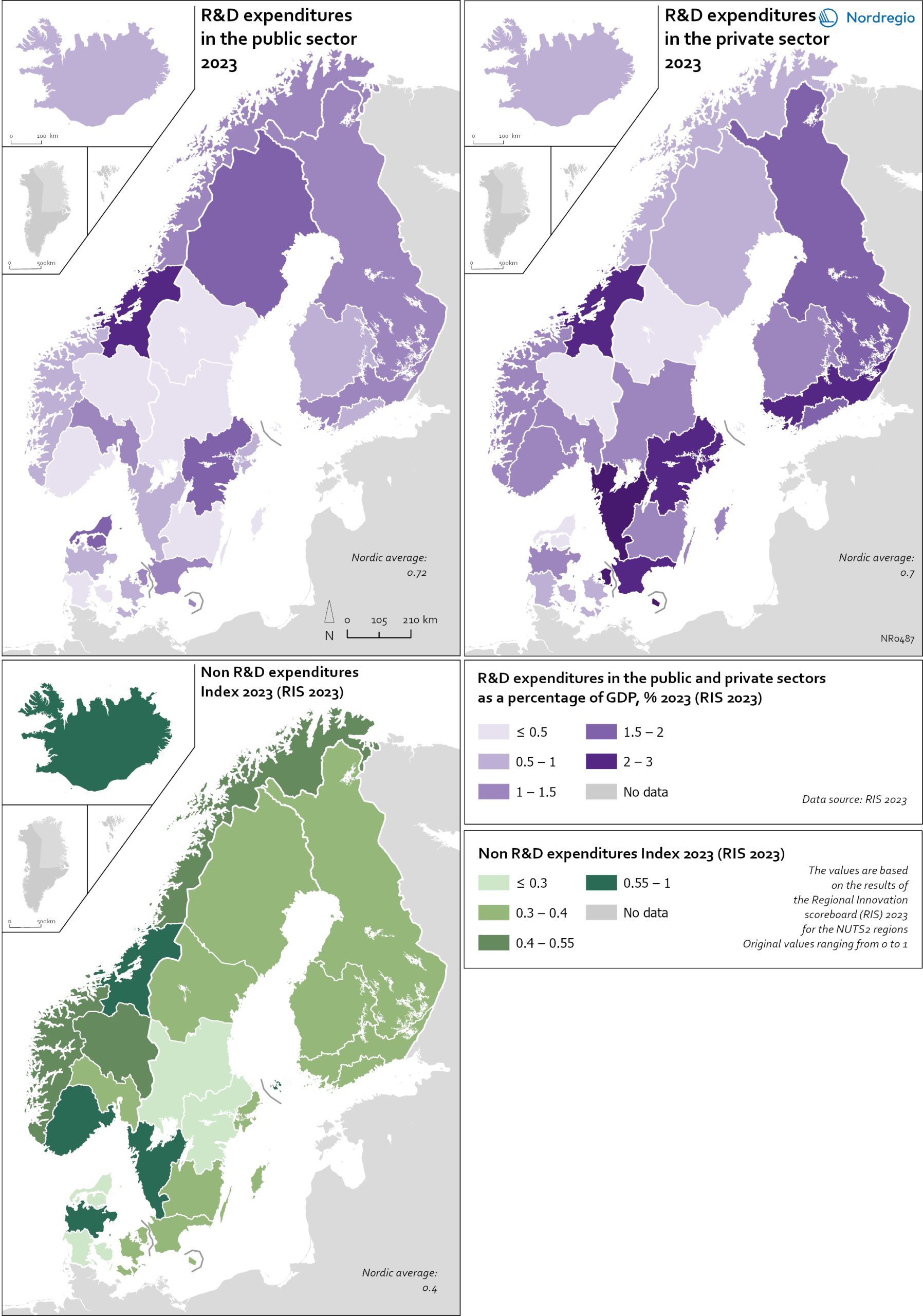

R&D and non-R&D expenditures in the public and private sector

These maps shows the expenditure on Research and Development (R&D) in the public and business sectors as a percentage of regional GDP, along with non-R&D innovation expenditure in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as a percentage of turnover. Together, these metrics offer a comprehensive understanding of the innovation landscape and provide insights into governments’ and higher education institutions’ commitment to foundational research, as well as the competitiveness and dynamism of the business environment and SMEs’ innovation capacity. By considering investment in both R&D and non-R&D activities, these indicators illustrate a broad spectrum of innovation drivers, from basic research to market-driven initiatives, and underscore the diverse pathways through which innovation fosters economic growth and social progress First, the top left map showcases R&D expenditure in the public sector as a percentage of GDP in the Nordic countries in 2023. In that year, the European level of R&D expenditure in the public sector, as a percentage of GDP, was 0.78%. By comparison, the Nordic average was 0.9%. While the more urban regions, in general, lead the Nordic regions, this is not always the case, as shown by the variation between the frontrunners. The leading region is Trøndelag (including Norway’s third-largest city, Trondheim), with 2.30% of regional GDP. It is in third place in the EU as a whole. The next regions are Övre Norrland with 1.77%, Northern Jutland with 1.54%, Östra Mellansverige with 1.52%, and Hovedstaden with 1.49%. A common feature of most of the top-ranking regions is that they host universities and other higher education institutions known for innovation practices. Most Nordic regions have not seen significant increases or decreases in public R&D spending between 2016 and 2023. The top right map focuses on the private sector’s investment in research and development activities and depicts R&D expenditure in the business sector…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

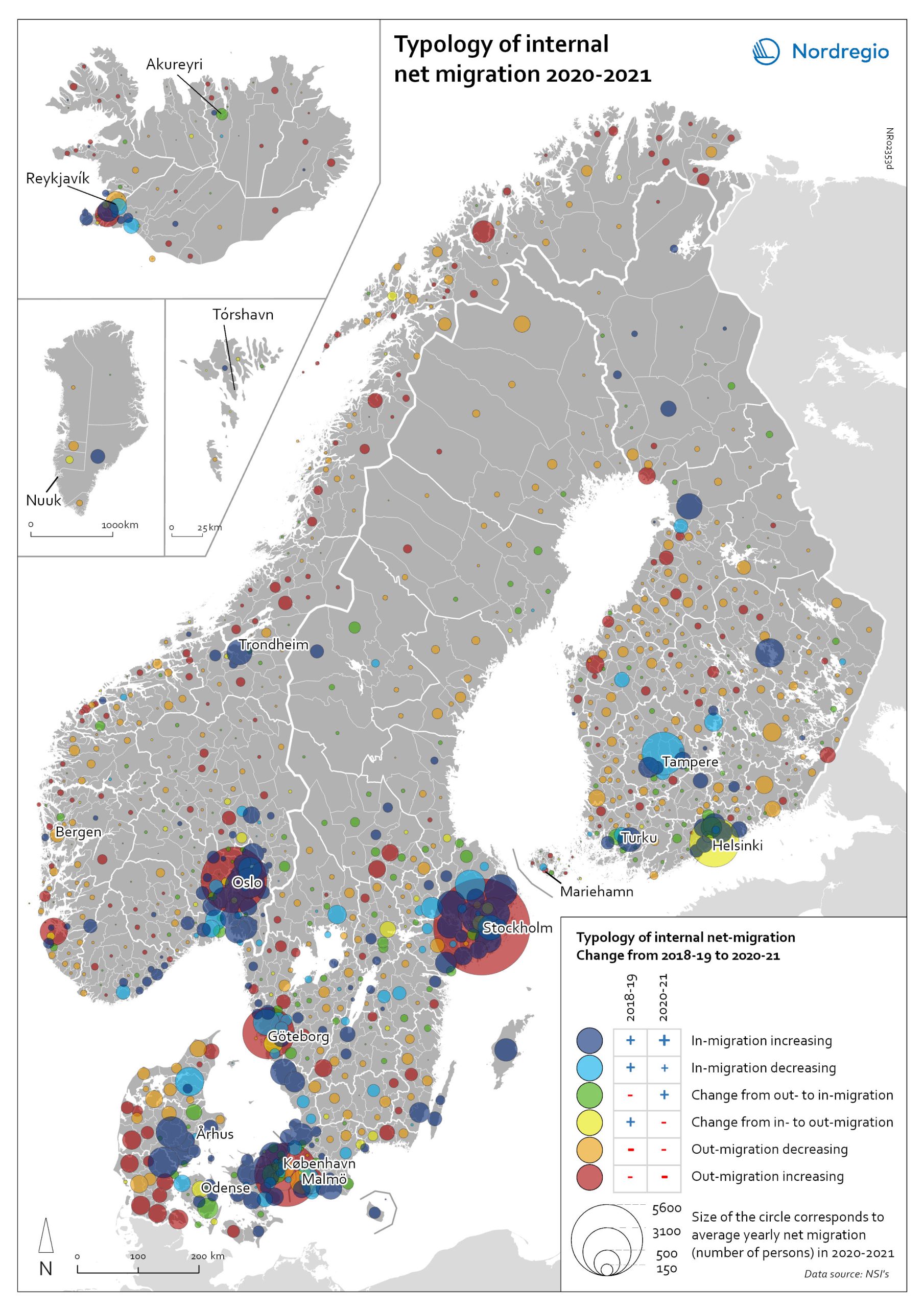

Typology of regional internal net migration 2020-2021

The map presents a typology of internal net migration in regions by considering average annual internal net migration in 2020-2021 alongside the same figure for 2018-2019. The colours on the map correspond to six possible migration trajectories: Dark blue: Internal net in migration as an acceleration of an existing trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) Light blue: Internal net in migration but at a slower rate than previously (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Green: Internal net in migration as a new trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net out-migration compared to 2018-2019) Yellow: Internal net out migration as a new trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net in-migration compared to 2018-2019) Orange: Internal net out migration but at a slower rate than previously (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Red: Internal net out migration as a continuation of an existing trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019)

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

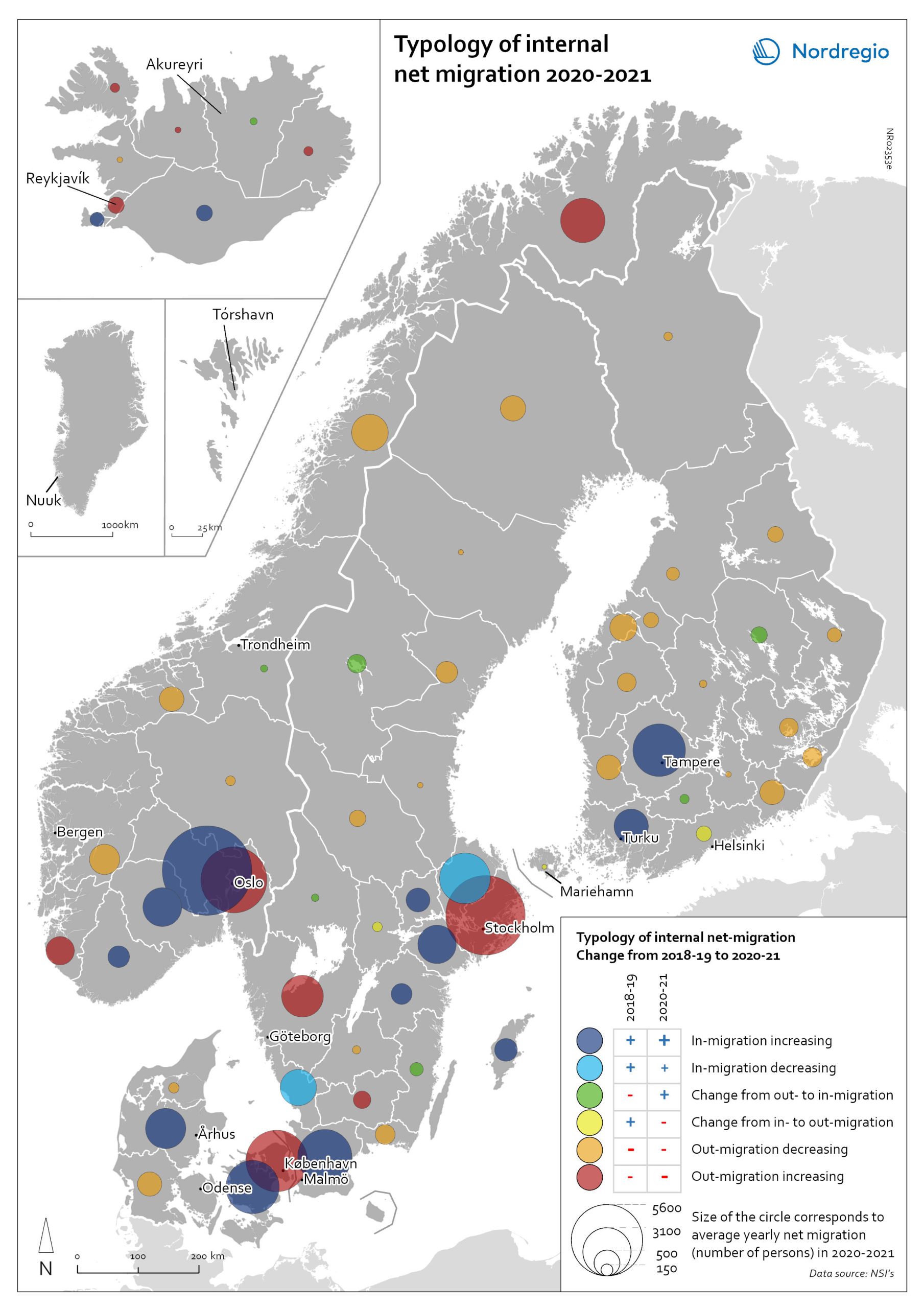

Typology of internal net migration 2020-2021

The map presents a typology of internal net migration by considering average annual internal net migration in 2020-2021 alongside the same figure for 2018-2019. The colours on the map correspond to six possible migration trajectories: Dark blue: Internal net in migration as an acceleration of an existing trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) Light blue: Internal net in migration but at a slower rate than previously (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Green: Internal net in migration as a new trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net out-migration compared to 2018-2019) Yellow: Internal net out migration as a new trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net in-migration compared to 2018-2019) Orange: Internal net out migration but at a slower rate than previously (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Red: Internal net out migration as a continuation of an existing trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) The patterns shown around the larger cities reinforces the message of increased suburbanisation as well as growth in smaller cities in proximity to large ones. In addition, the map shows that this is in many cases an accelerated (dark blue circles), or even new development (green circles). Interestingly, although accelerated by the pandemic, internal out migration from the capitals and other large cities was an existing trend. Helsinki stands out as an exception in this regard, having gone from positive to negative internal net migration (yellow circles). Similarly, slower rates of in migration are evident in the two next largest Finnish cities, Tampere and Turku (light blue circles). Akureyri (Iceland) provides an interesting example of an intermediate city which began to attract residents during the pandemic despite experiencing internal outmigration prior. From a rural perspective there are…

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

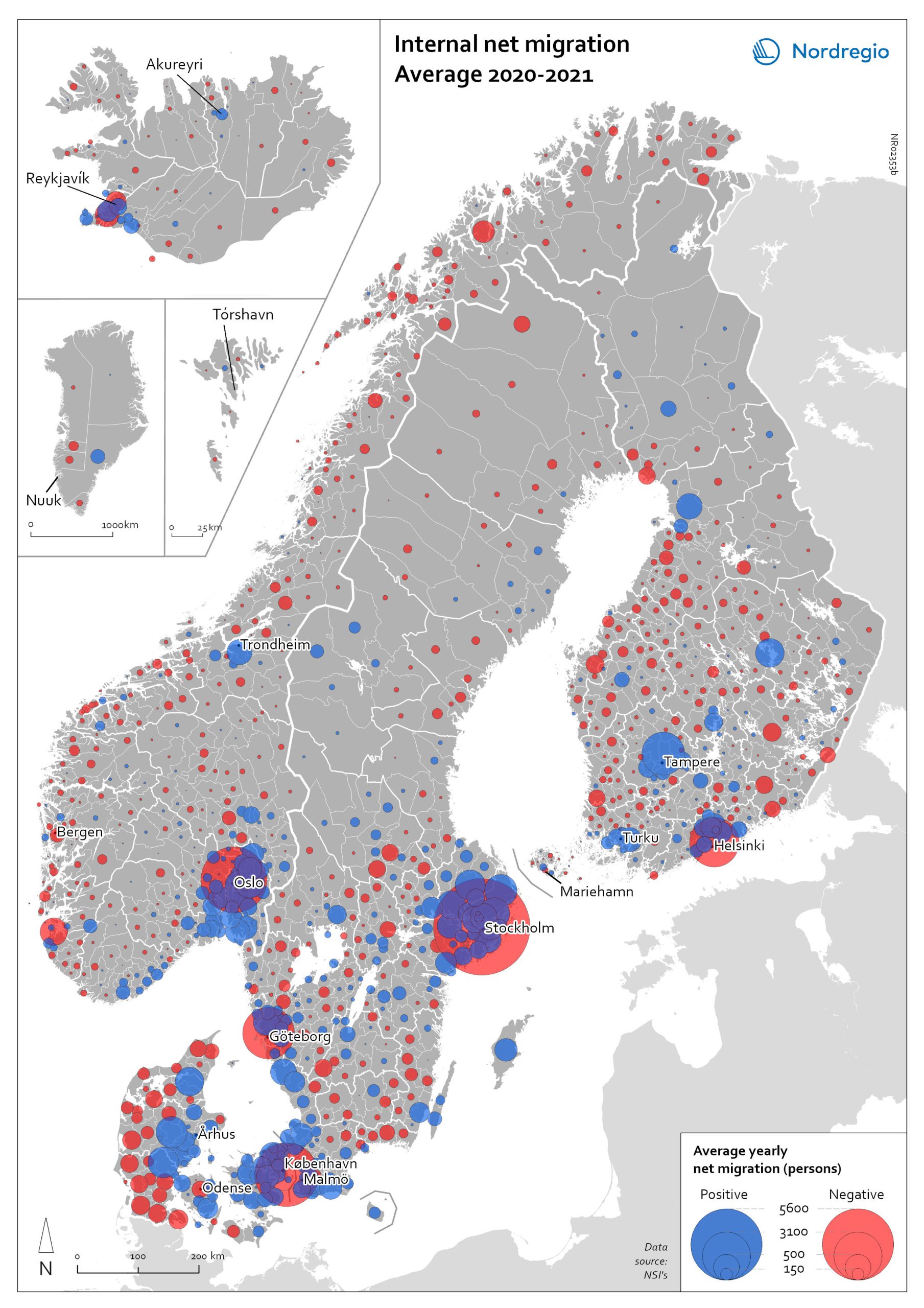

Internal net migration 2020-2021

The map shows the average internal net migration in 2020 and 2021 for Nordic municipalities. Blue dots indicate positive internal net migration (more people moving in than out) and red dots indicate negative internal net migration (more people moving out than in), while the size of the dots represents the extent of the positive or negative trend. Internal migration refers to a change of address within the same country. The map shows substantial outmigration from the Nordic capitals, as well as from Gothenburg and Malmö in Sweden. Alongside increased suburbanisation, the map also provides some evidence of growth in medium-sized cities and smaller cities within commuting distance of larger cities.

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

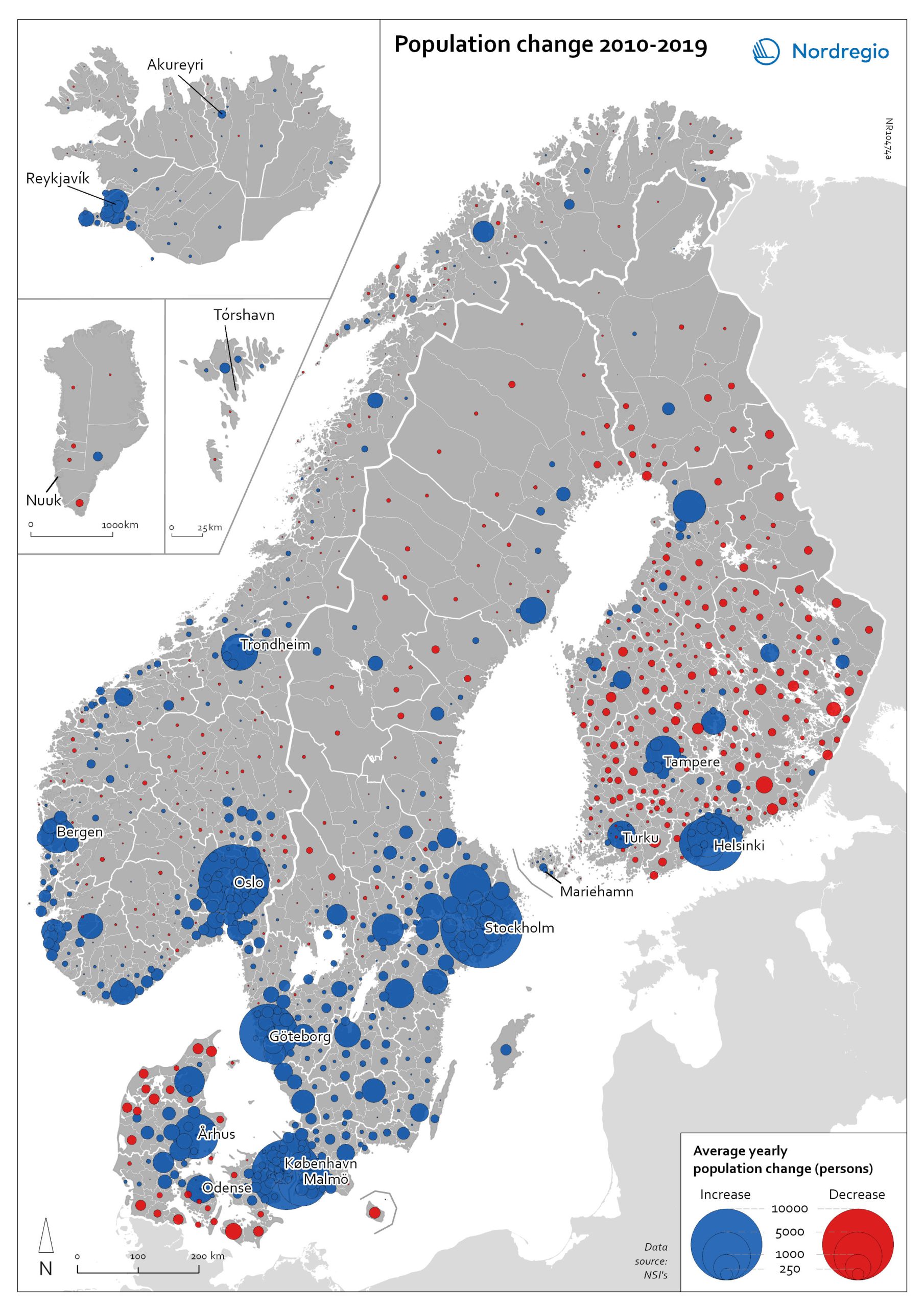

Population change 2010-2019

The map shows the type (positive or negative) and size of population change from 2010 to 2019 in all nordic municipalities. In Finland, Denmark, and Greenland there is a clear pattern of population growth in and around the larger cities and population decline in rural areas. Geographical and administrative differences mean that a much larger number of rural municipalities in Finland are dealing with population decline. Sweden experienced substantial population growth between 2010 and 2019, primarily due to high levels of international immigration. As a result, many rural areas also experienced population growth, particularly in the south of Sweden. However, in the more sparsely populated municipalities in the north of Sweden, the pattern is somewhat similar to that observed in Denmark and Finland, albeit with population decline in lower absolute numbers. Both Iceland and the Faroe Islands experienced substantial growth of their tourism industries within the period. This enabled some rural areas to maintain or even grow their populations. Norway exhibits more balanced population development in general, with a mix of population growth and decline in rural areas throughout the country.

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

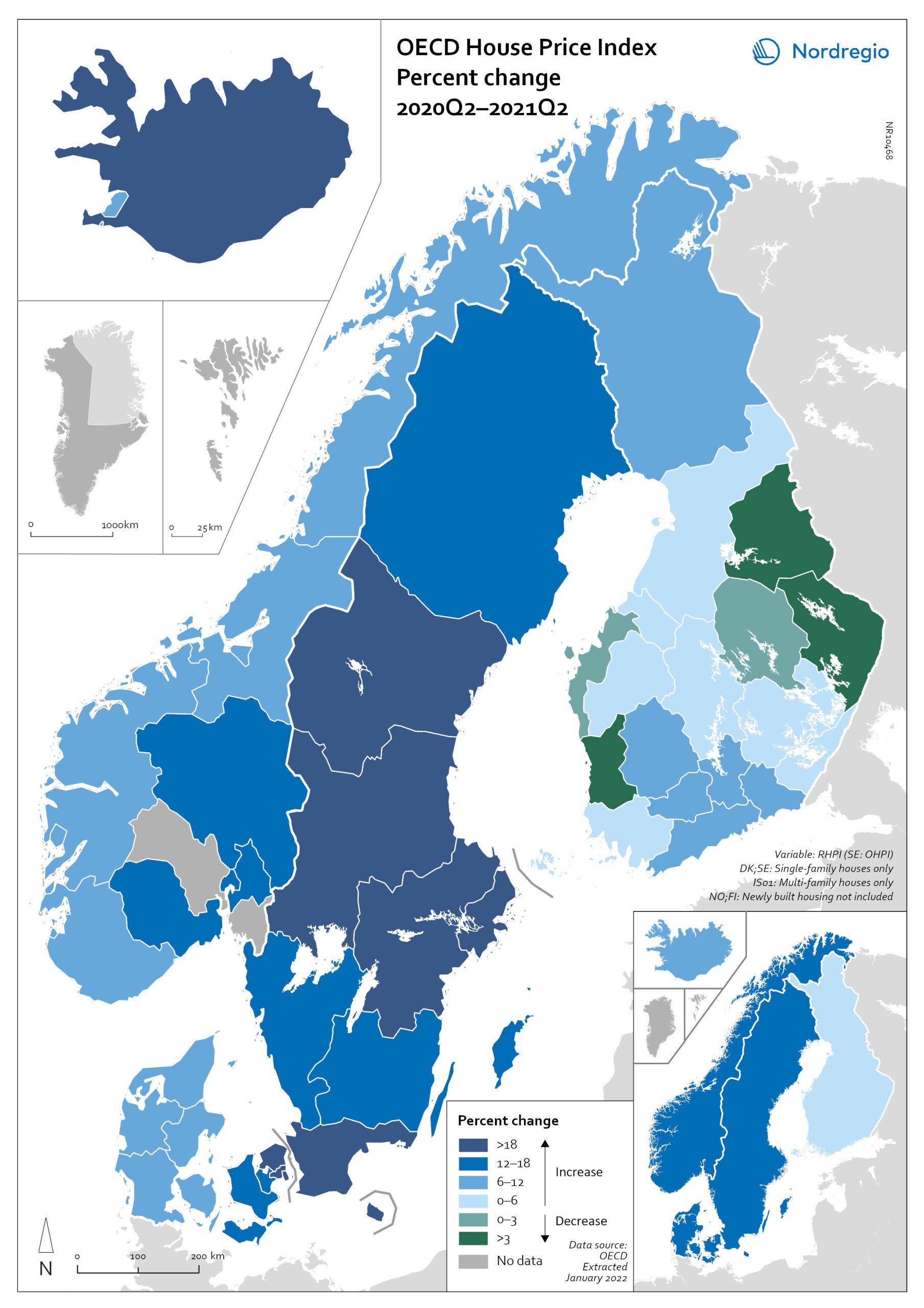

OECD House Price Index. Change 2020Q2–2021Q2

The map shows the relative change of the OECD House Price Index from Q2 2020 to Q2 2021. The map shows that the price development was not uniform within the countries. Iceland recorded the largest price increases overall, with the most marked price increases found outside of the capital region. All Swedish regions recorded increases above 20%, with the highest increases in the Stockholm and Malmö regions. All Norwegian regions showed price increases, though to a lesser extent than Swedish regions in most cases. In Denmark, Bornholm, Sjælland and the rural islands of Lolland and Falster recorded relatively high price increases, although many rural areas developed from low absolute prices in 2020. Finland was the only country where some regions saw property prices decrease. Moderate increases were still observed in some of the southern regions, where the major cities are located, and in the north.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

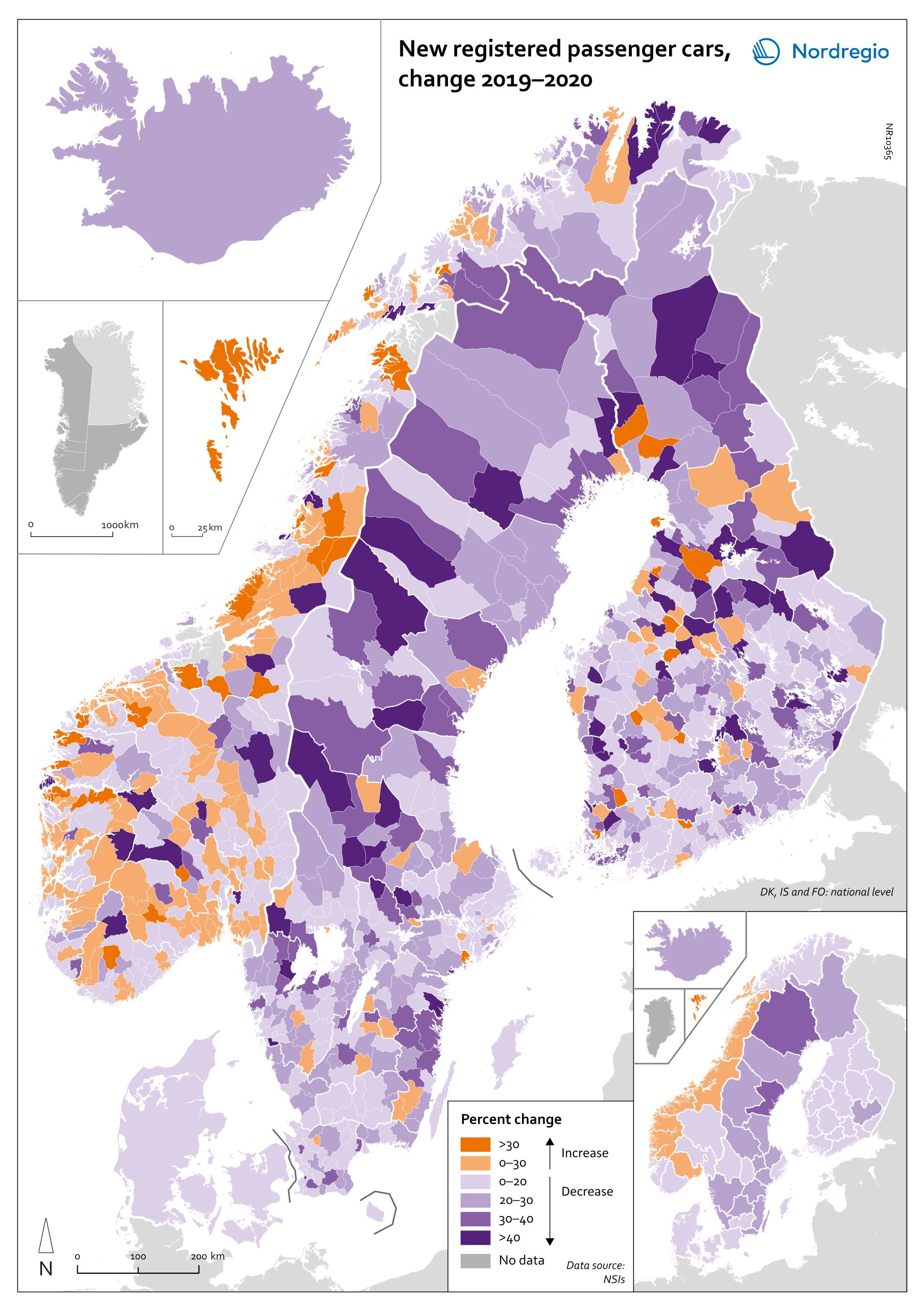

Change in new registered cars 2019-2020

The map shows the change in new registered passenger cars from 2019 to 2020. In most countries, the number of car registrations fell in 2020 compared to 2019. On a global scale, it is estimated that sales of motor vehicles fell by 14%. In the EU, passenger car registrations during the first three quarters of 2020 dropped by 28.8%. The recovery of consumption during Q4 2020 brought the total contraction for the year down to 23.7%, or 3 million fewer cars sold than in 2019. In the Nordic countries, consumer behaviour was consistent overall with the EU and the rest of the world. However, Iceland, Sweden, Finland, Åland, and Denmark recorded falls of 22%–11% – a far more severe decline than Norway, where the market only fell by 2.0%. The Faroe Islands was the only Nordic country to record more car registrations, up 15.8% in 2020 compared to 2019. In Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, there were differences in car registrations in different parts of the country. In Sweden and Finland, the position was more or less the same in the whole of the country, with only a few municipalities sticking out. In Finland and Sweden, net increases in car registrations were concentrated in rural areas, while in major urban areas, such as Uusimaa-Nyland in Finland and Västra Götaland and Stockholm in Sweden, car sales fell between 10%–22%. Net increases in Norway were recorded in many municipalities throughout the whole country in 2020 compared to 2019.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Transport

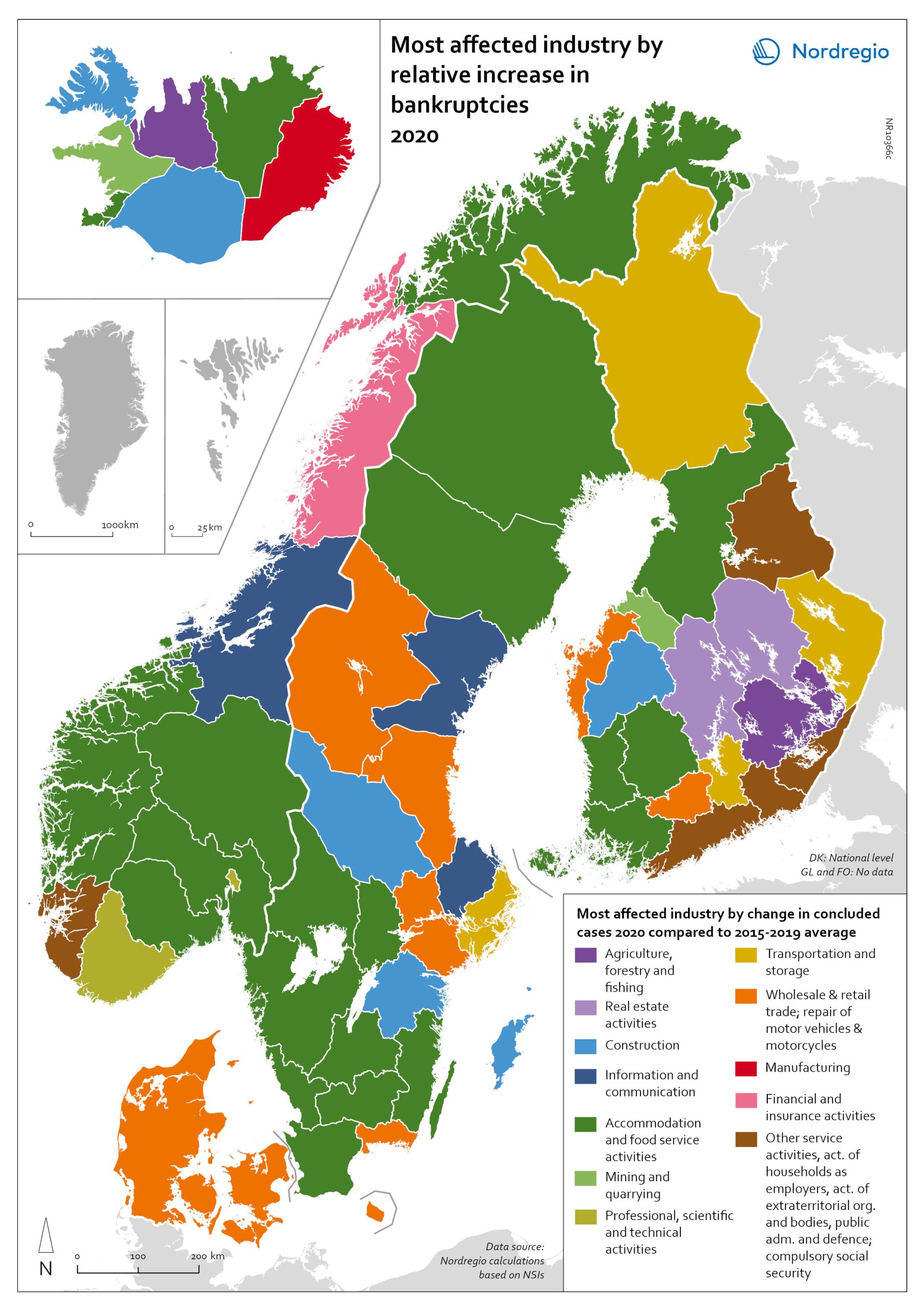

Bankruptcies in 2020 by industry and region

The map shows the most affected industry by relative increase in concluded business bankruptcies 2020 compared to 2015–2019 average. Regional patterns in business failures are linked to factors ranging from the effectiveness of the measures adopted by the various governments to the exposure of regional economies to vulnerable sectors. Regions with higher numbers of bankruptcies tend to reflect the concentration of economic activity in sectors particularly affected by the pandemic. It comes as little surprise that Accommodation and food service activities were the industries with the largest increase in business bankruptcies in 2020 compared to the 2015–2019 baseline. In the Nordic Region as a whole, the number rose by 28.6%. This pattern is also discernible at the regional level. Hotels and restaurants were the activities with the biggest increase in the number of bankruptcies in a significant number of Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish regions. Other sectors suffering higher-than-average numbers of business bankruptcies are service industries, particularly those requiring closer social interaction, like Education (16.5% increase), Other service activities (12.0% increase) and Administrative and support service activities (7.9% increase). The logistics sector was also greatly affected, with major impact localised around logistics centres and transport nodes in the different countries. In the capital regions of Oslo, Stockholm and Helsinki, Transportation and storage was the sector with the largest increase in bankruptcies. Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles was the industry to suffer the most in Denmark and several Finnish and Swedish regions.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

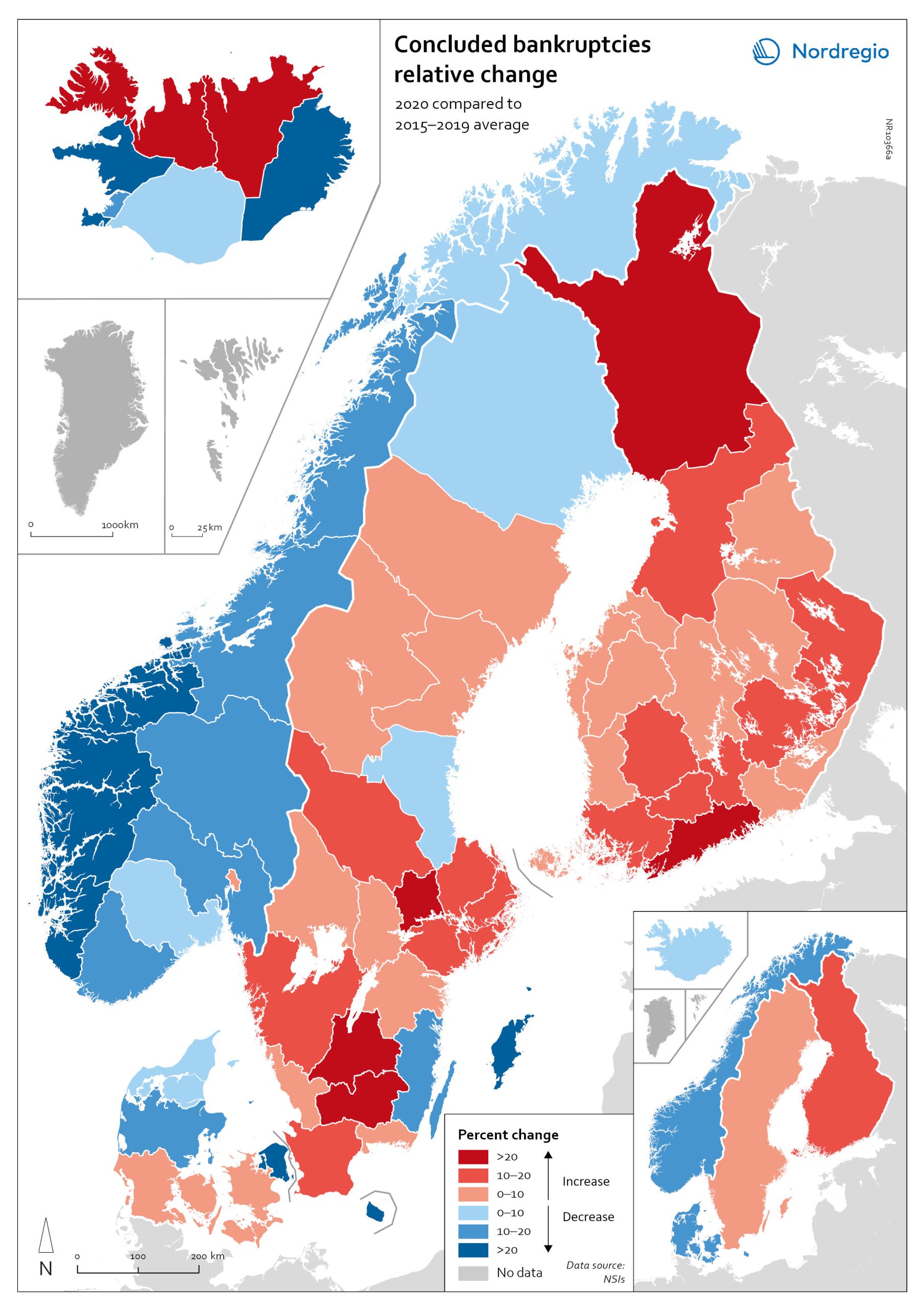

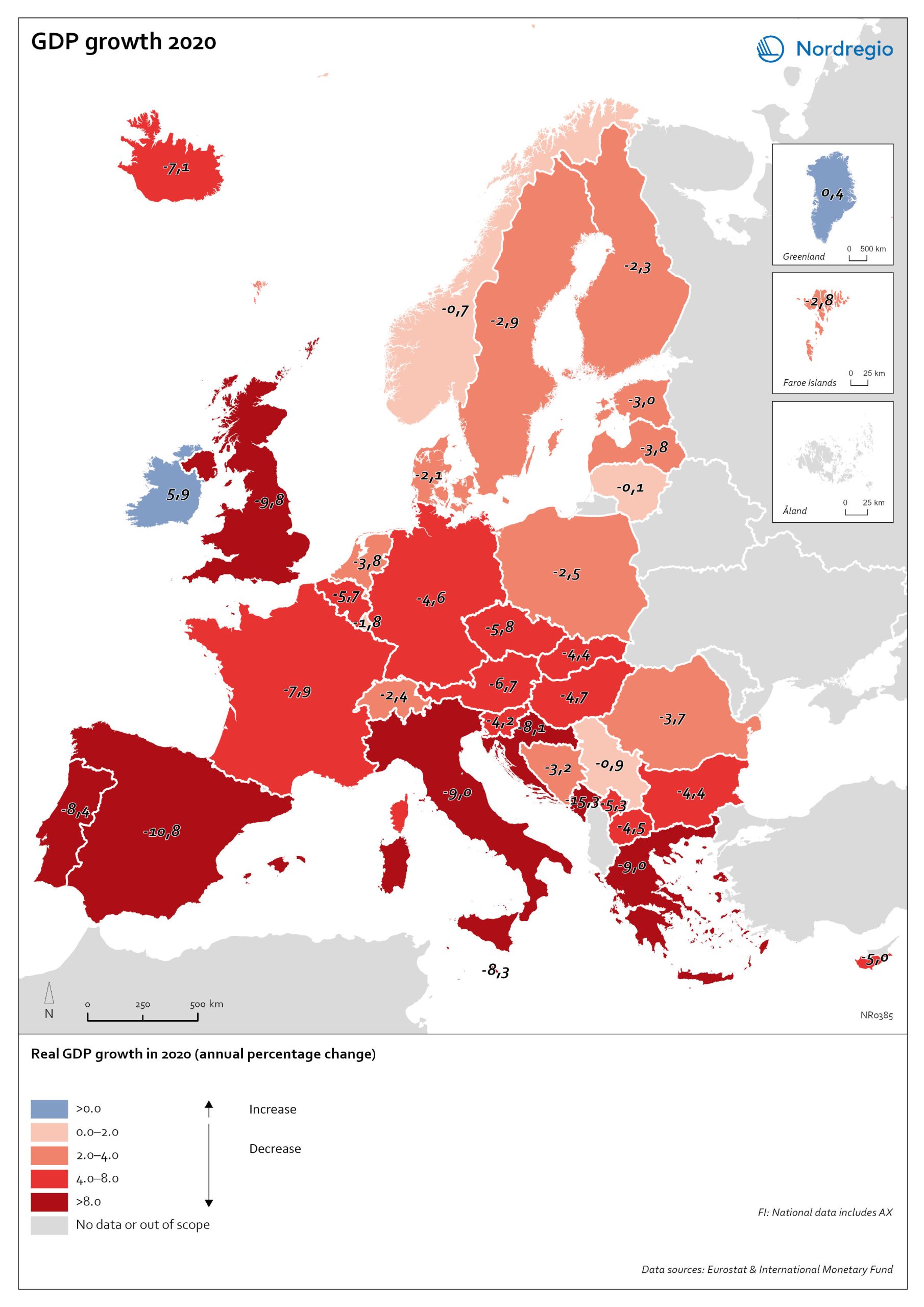

Relative change in the number of business bankruptcies

The map shows the relative change in the number of concluded business bankruptcies by region, 2015–2019 average compared to 2020. At sub-national levels, the distribution of business bankruptcies does not show a clear territorial pattern. In Iceland and Denmark, businesses in the most urbanised areas, including the capital regions, seem to have been those that benefited most from the economic mitigation measures (-23.9% in Höfuðborgarsvæðið and -24.4% in Region Hovedstaden). By contrast, Oslo is the only Norwegian region where there were more business bankruptcies in 2020 compared to the 2015–2019 baseline (1.9% increase). Most Norwegian regions did, in fact, have fewer bankruptcies in 2020, particularly in the western regions. One plausible explanation for this could be that the number of business failures during the baseline period was especially high in western Norway due to the fall in oil prices in 2014–2015. In Sweden the situation is even more mixed. Here, businesses in urban areas seem to have been more exposed to the distress caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. The most urbanised regions in the Stockholm-Gothenburg-Malmö corridor registered a greater increase in liquidations (Jönköping, Kronoberg and Södermanland regions saw surges of around 20%). However, predominantly rural regions in Sweden, such as Västerbotten and Jämtland, also recorded higher numbers of bankruptcies than average (9.8% and 8.8% increase, respectively). In Finland, the impact was greater in Lapland (26.9%) and around Helsinki (Uusimaa, 25.9%) than in the central parts of the country. Åland also experienced a moderate rise in business bankruptcies in 2020 (4.0%), mostly related to the tourism sector.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

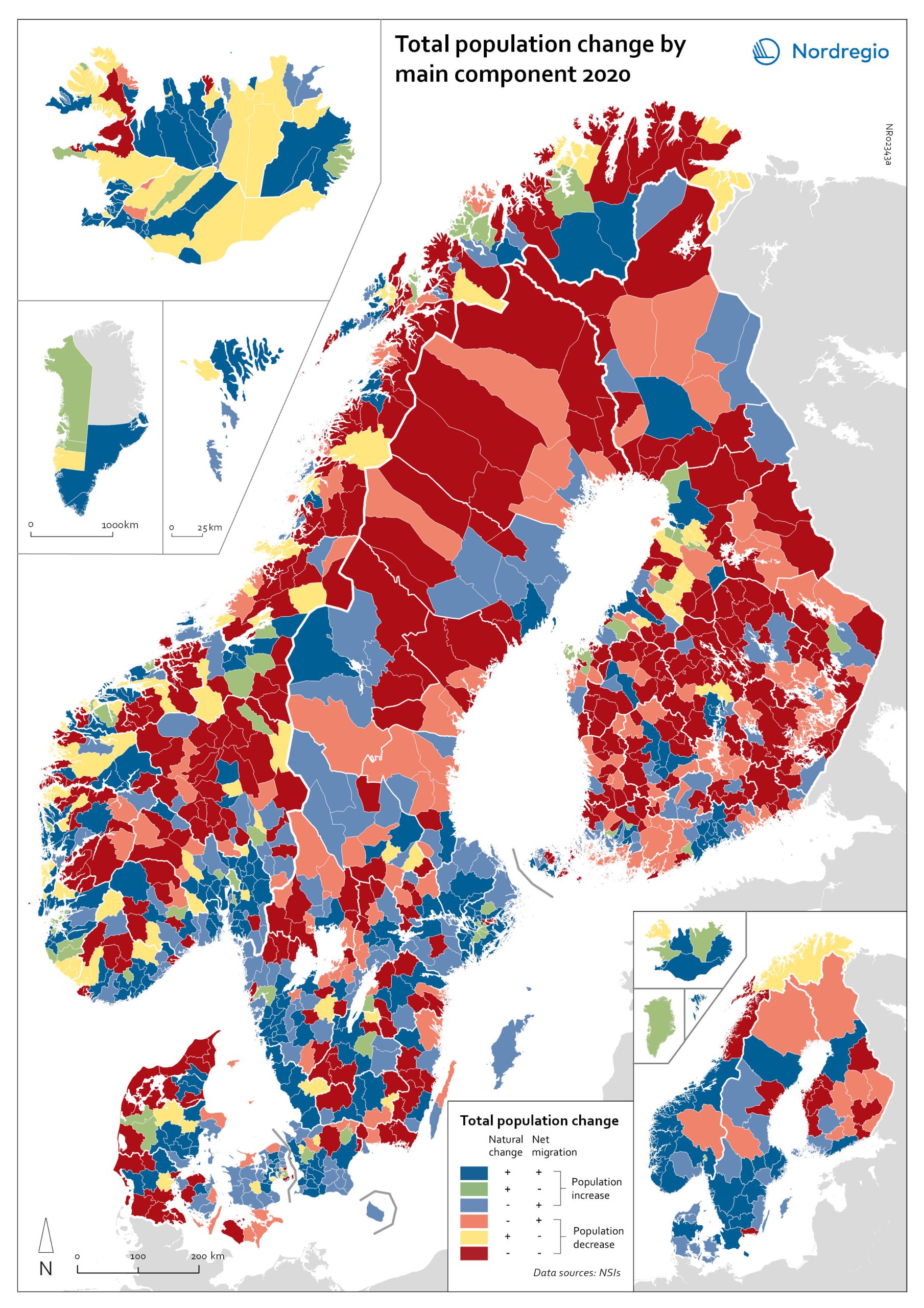

Population change by component 2020

The map shows the population change by component 2020. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2010-2019. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

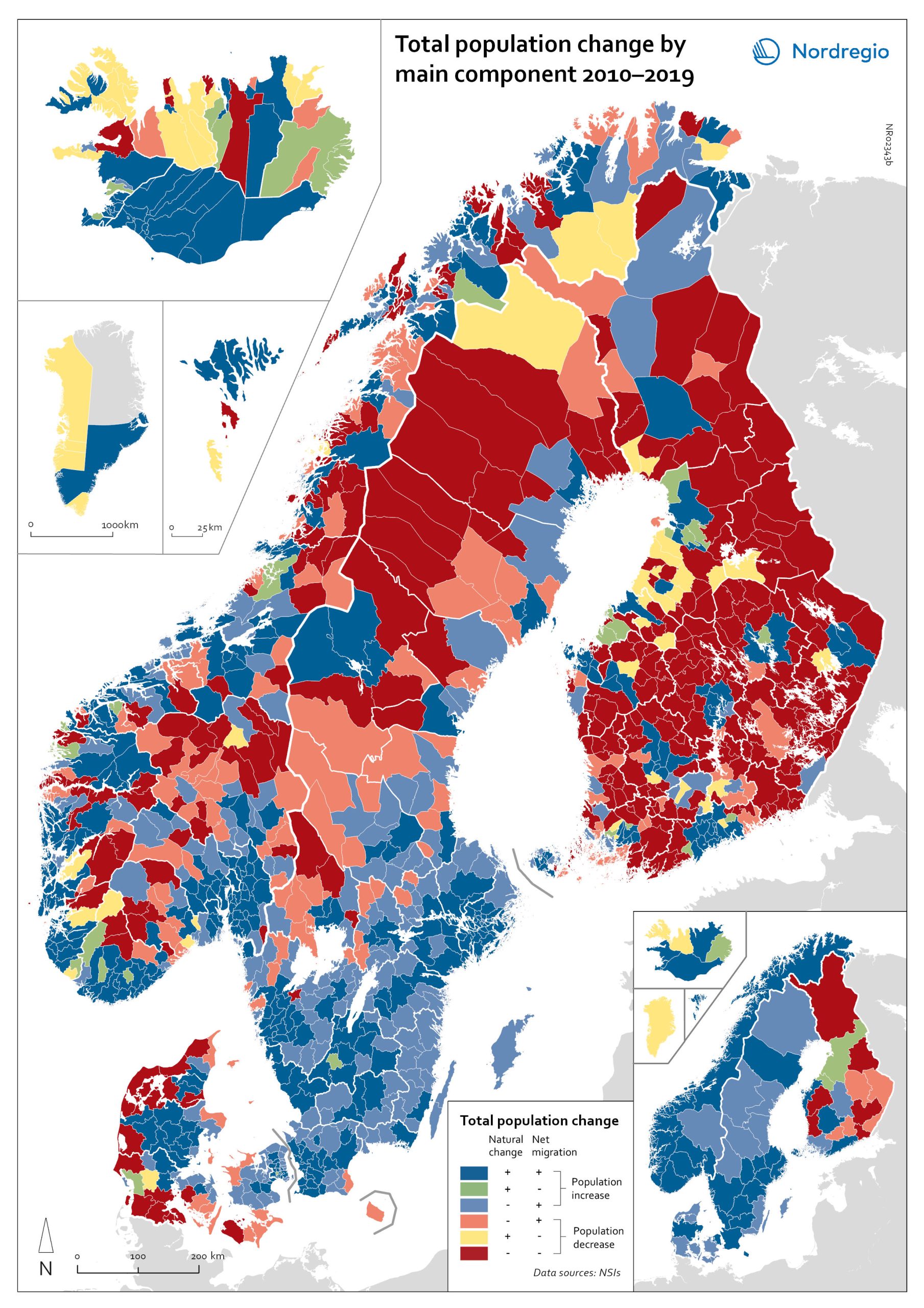

Population change by component 2010-2019

The map shows the population change by component 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2020. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

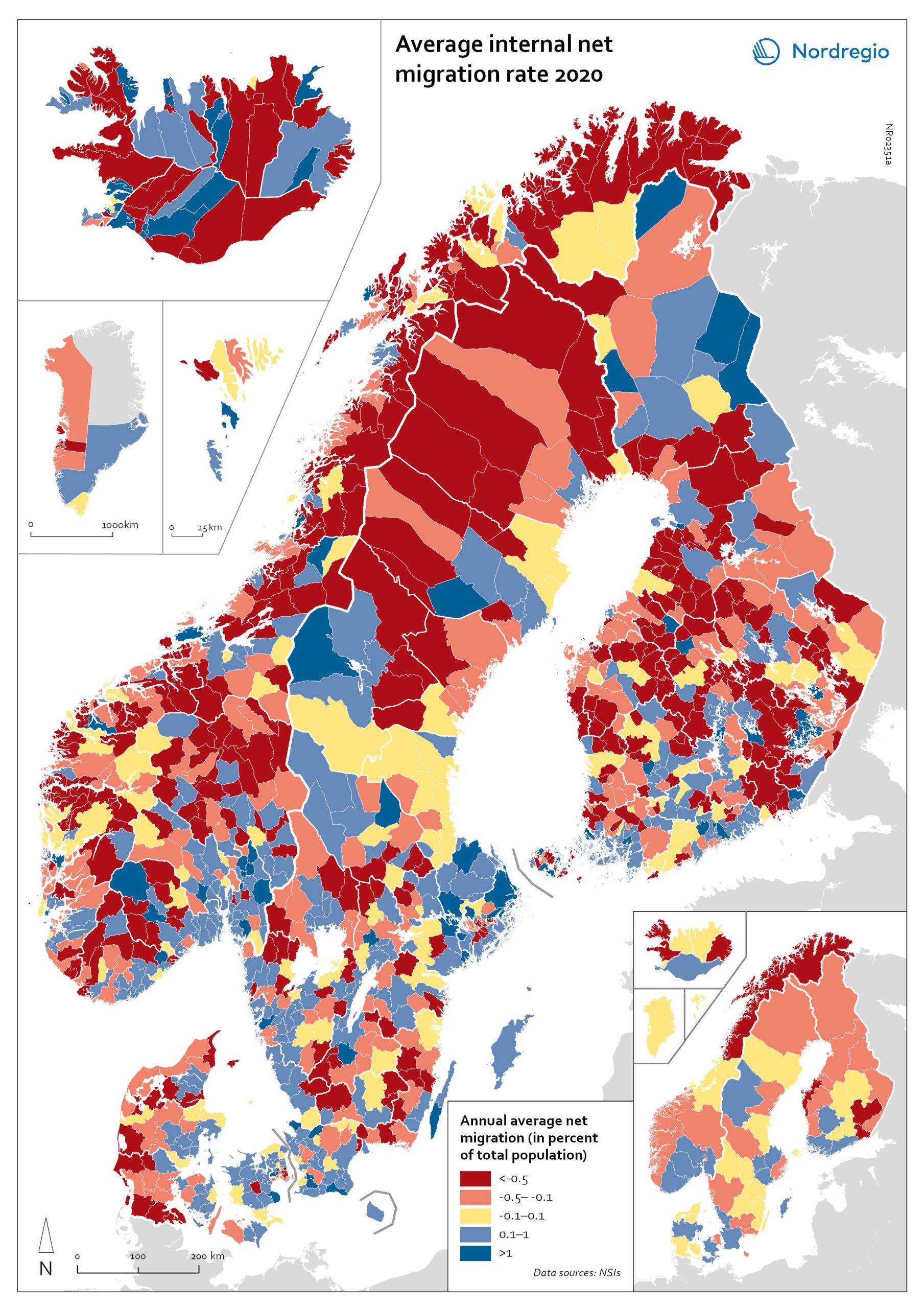

Net internal migration rate 2020

The map shows the internal net migration in 2020. The map is related to the same map showing net internal migration in 2010-2019. The maps show several interesting patterns, suggesting that there may be an increasing trend towards urban-to-rural countermigration in all the five Nordic countries because of the pandemic. In other words, there are several rural municipalities – both in sparsely populated areas and areas close to major cities – that have experienced considerable increases in internal net migration. In Finland, for instance, there are several municipalities in Lapland that attracted return migrants to a considerable degree in 2020 (e.g., Kolari, Salla, and Savukoski). Swedish municipalities with increasing internal net migration include municipalities in both remote rural regions (e.g., Åre) and municipalities in the vicinity of major cities (e.g., Trosa, Upplands-Bro, Lekeberg, and Österåker). In Iceland, there are several remote municipalities that have experienced a rapid transformation from a strong outflow to an inflow of internal migration (e.g., Ásahreppur, Tálknafjarðarhreppurand, and Fljótsdalshreppur). In Denmark and Norway, there are also several rural municipalities with increasing internal net migration (e.g., Christiansø in Denmark), even if the patterns are somewhat more restrained compared to the other Nordic countries. Interestingly, several municipalities in capital regions are experiencing a steep decrease in internal migration (e.g., Helsinki, Espoo, Copenhagen and Stockholm). At regional level, such decreases are noted in the capital regions of Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Stockholm. At the same time, the rural regions of Jämtland, Kalmar, Sjælland, Nordjylland, Norðurland vestra, Norðurland eystra and Kainuu recorded increases in internal net migration. While some of the evolving patterns of counterurbanisation were noted before 2020 for the 30–40 age group, these trends seem to have been strengthened by the pandemic. In addition to return migration, there may be a larger share of young adults who decide to…

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region