99 Maps

Foreign-born share 2022

This map shows the share of foreign-born of the total population in the Nordic countries. This map shows the share of foreign-born of the total population in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map), and municipalities (big map) in 2022. Iceland has the highest share of foreign-born residents in the Nordic Region, at 22%. Mýrdalshreppur, the municipality in the south containing the village of Vik, has the largest foreign-born population, at 58%. It is also the only municipality in the Nordic Region with a majority non-native population. Other municipalities in the south, some of which are quite small, also have significant foreign-born populations. Reykjanesbær, near Keflavik airport, is the largest municipality with a sizeable foreign-born population, at 29%. In Reykjavíkurborg, 20% of the population is foreign-born, about the same as the national average. Many municipalities with tiny populations in the Westfjords and the north also have small shares of foreign-born persons. In 2022, 17% of the population of Norway was foreign-born. Municipalities with high shares of foreign-born include Oslo (28%), several suburban municipalities near Oslo, and a few in the north – which have small overall populations but large numbers of foreign workers employed in the fishing industry. In Sweden, 20% of residents are foreign-born, with large differences in distribution by region and municipality. At the regional level, Stockholm has the highest share of foreign-born persons (27%), followed by Skåne, including the city of Malmö (24%). The percentage of foreign-born persons in Västra Götaland, which encompasses Gothenburg, is the same as that of Sweden as a whole. The regions with low shares of foreign-born persons are in the north of the country – Dalarna, Gävleborg, Västernorrland, Jämtland, Västerbotten, and Norrbotten – plus the island of Gotland, which has the lowest share (9%). There are no municipalities in which foreign-born…

2025 April

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Foreign-born change (%) 2000-2022

This map shows the percentage-point change in foreign-born populations in the Nordic countries. This map shows the percentage-point change in foreign-born populations by region (small map) and municipality (big map) between 2000 and 2022. The blue shades indicate an increase in the number of foreign-born while the red shades indicate a decrease. The recent growth in foreign-born populations differs among the Nordic countries, regions, and municipalities. During the period 2000-2022, much of both the absolute and percentage-point increases in the foreign-born populations took place in suburbs around the capital cities and other large urban centres. However, with few exceptions, every municipality across the Nordic Region saw increases in foreign-born populations. In Iceland, the foreign-born population increased from 5% to 20%. The largest percentage-point increases in the foreign-born populations were in municipalities in the southwest, which had small populations and small foreign-born shares. Of the larger municipalities, Reykjanesbaer and the Capital Region had the largest absolute and percentage point increases. The foreign-born population in Norway grew from 7% to 17%. The municipalities with significant increases in foreign-born populations include several suburban areas near Oslo, as well as scattered municipalities elsewhere that had small foreign-born shares in 2000. The percentage of foreign-born residents in Oslo increased from 16% to 28% between 2000 and 2022. No municipalities experienced a decline in foreign-born population during this period.

2025 April

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Internal Migration 2021

This map shows the internal net migration in 2021 as a percentage of the total population. This map shows the internal net migration in 2021 as a percentage of the total population. The small map shows the result on a regional level, and the big map on the municipal level. Internal (sometimes referred to as domestic) net migration refers to migration between municipalities and regions within the same country. International migration is excluded. In 2021, internal net migration was positive (indicated by shades of blue) or at least balanced (shown in yellow) in many of the municipalities in central and northern Sweden and in central and eastern Finland – areas that traditionally were more likely to lose population due to internal migration. Conversely, several municipalities in the capital regions – such as Stockholm, Oslo, and Copenhagen – exhibited negative internal net migration. Iceland, Greenland, and Åland exhibited mixed internal migration flows, with some municipalities experiencing positive net migration while others faced negative net migration. The Faroe Islands stand as an exception, maintaining only positive internal migration at the municipal level for this year.

2025 April

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

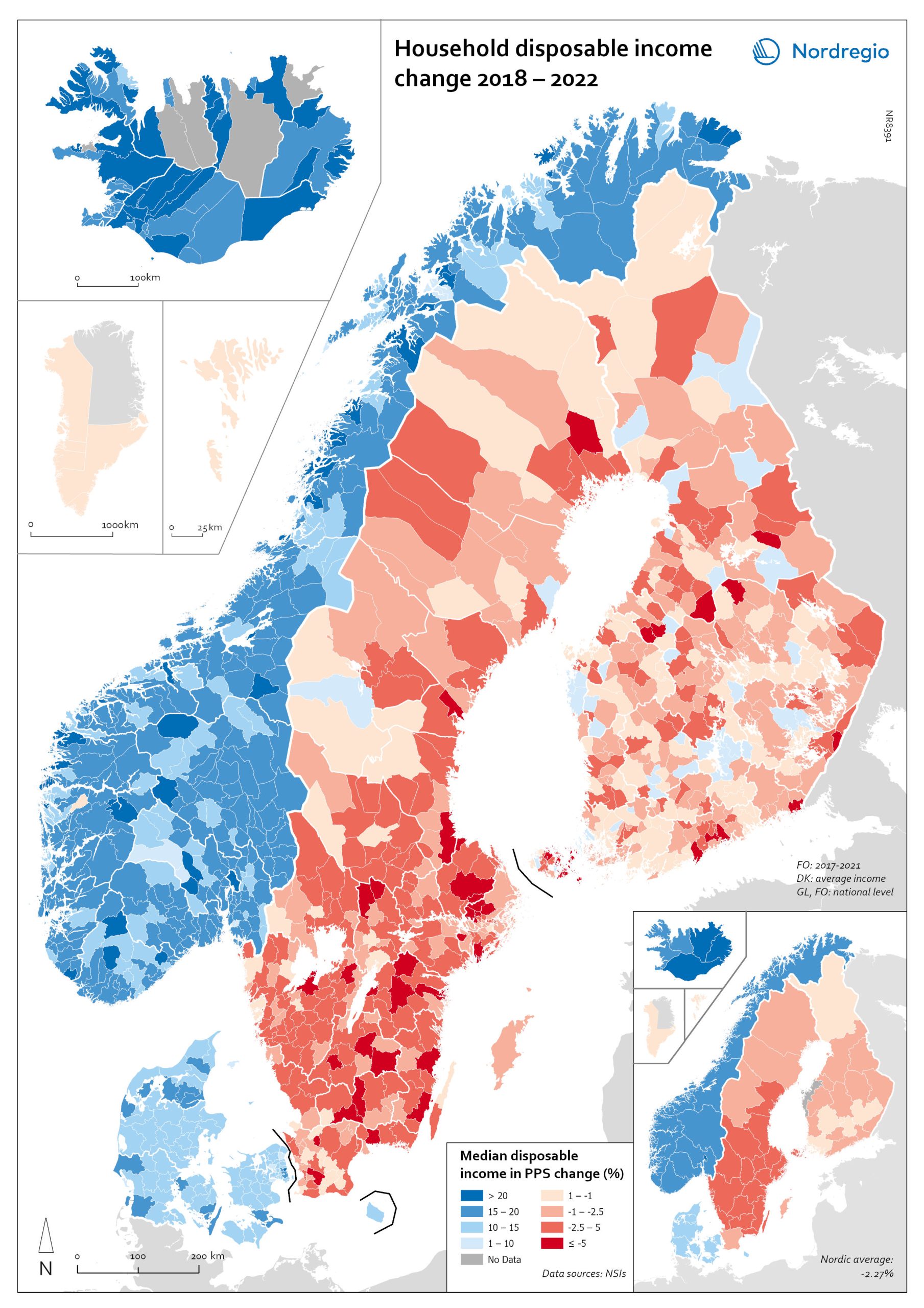

Household disposable income change 2018-2022

This map shows the percentage change in household disposable income between 2018 and 2022 in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map). Household disposable income per capita is a common indicator of the affluence of households and, therefore, of the material quality of life. It reflects the income generated by production, measured as GDP that remains in the regions and is financially available to households, excluding those parts of GDP retained by corporations and government. In sum, household disposable income is what households have available for spending and saving after taxes and transfers. It is ‘equivalised’ – adjusted for household size and composition – to enable comparison across all households. Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) is used to compare the countries’ economies and the cost of living for households. As shown in the map, between 2018 and 2022, household disposable income increased for all Danish, Icelandic, and Norwegian municipalities and decreased for Finnish and Swedish municipalities. On average, the city municipalities have higher incomes and increased most in Finland and Sweden in 2018–2022. In Sweden, a tendency towards larger falls in income was observed in several southern municipalities. In summary, absolute household income increased in all Nordic countries but not when measured in purchasing power. Based on this metric, on average, Norwegian households are the most well-off and Iceland the worst off, while Danish households benefited from a stronger currency in 2022. Single-parent households have had lower increases in household income than other families in Norway and parts of Sweden. Municipalities show a similar trend in Norway and Denmark, although Norwegian coastal municipalities fared slightly better in 2022. Disposable income is falling in all Swedish and Finnish municipalities.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

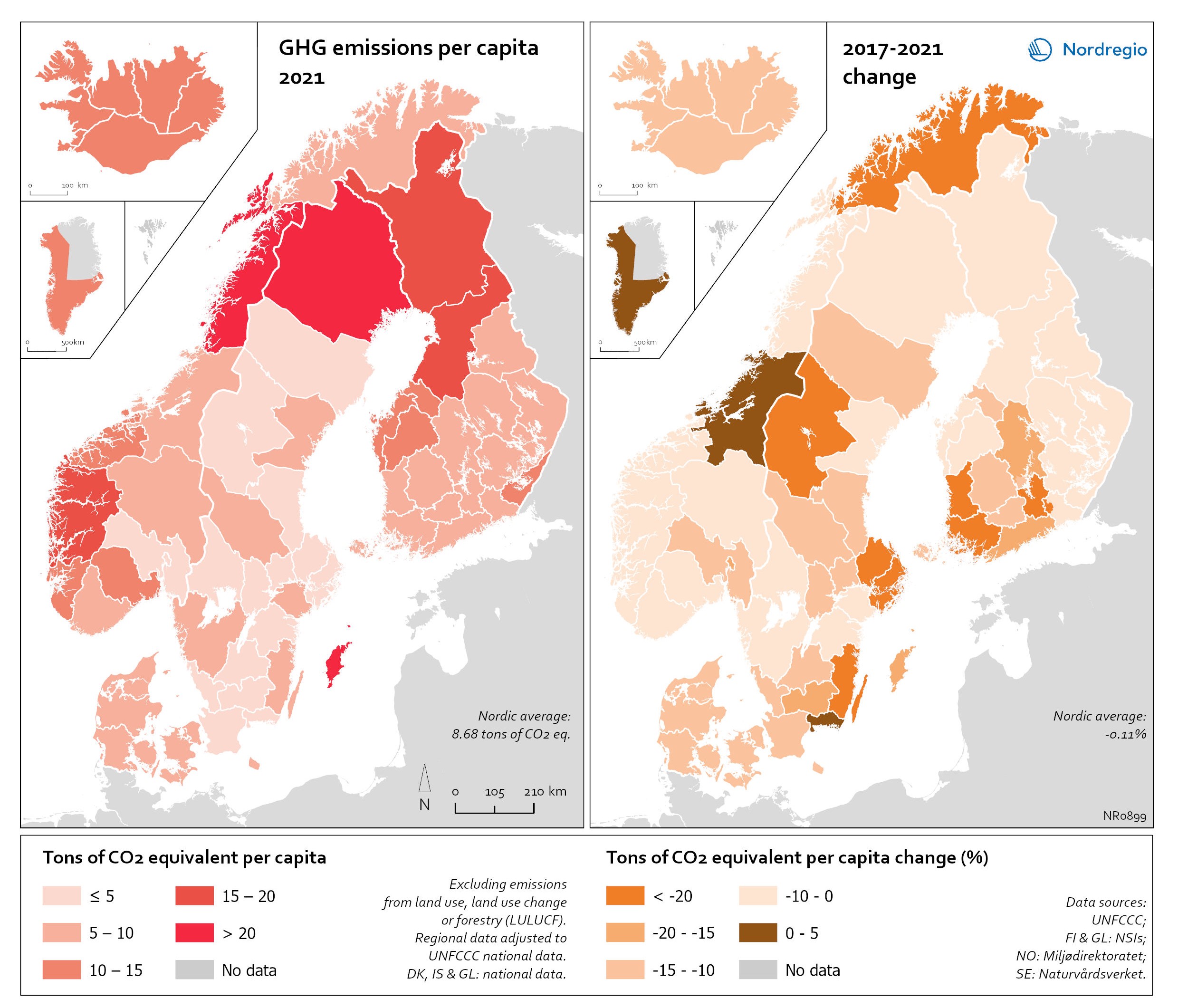

Regional GHG emissions per capita in 2021 and change 2017-2021 on a territorial basis

The data excludes emissions from land use, land use change or forestry (LULUCF). The regional data has been adjusted to UNFCCC national data. The data for Denmark, Iceland and Greenland is on national level. It should be noted that displaying emissions on a territorial basis may be skewed due to the inter-regional dynamics of energy processes, natural resource distributions and concentrations of industrial activities. From 2017 to 2021, the Nordic regions cut their per-capita GHG emissions by on average 11.3%, with an overall Nordic average fall of 8.7% over the same period. In regions historically reliant on fossil fuels for heat and power generation, emissions have continued to decline. This trend is evident in Denmark, as well as in Southern Sweden and Southern Finland – densely populated areas that have taken steps toward expanding district heating coverage and reducing carbon intensity. The largest decrease in GHG emissions per capita was found in Troms and Finnmark, with a 42.3% decrease, Satakunta with a 30.2% decrease and Päijät-Häme – Päijänne-Tavastland with a 29.2% decrease. Only three regions (Greenland, Trøndelag and Blekinge) saw an increase in GHG emissions per capita. At an aggregated level, industrial-related emissions decreased throughout the Nordic Region, but this trend does not hold true for regions in Norway with intensive offshore oil and gas operations. For instance, Nordland, Vestland, Møre og Romsdal, Vestfold and Telemark exhibited the highest per capita emissions in 2021. Between 2017 and 2021, emissions were increasing in many Norwegian regions with intensive offshore oil and gas activity, but also in Norrbotten in Sweden (21.2 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per capita) and Gotland (33.6 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per capita) due to intensive activity in the metal and cement industries, respectively, as well as in several Finnish regions. At the other end of the scale, the…

2025 April

- Environment

- Nordic Region

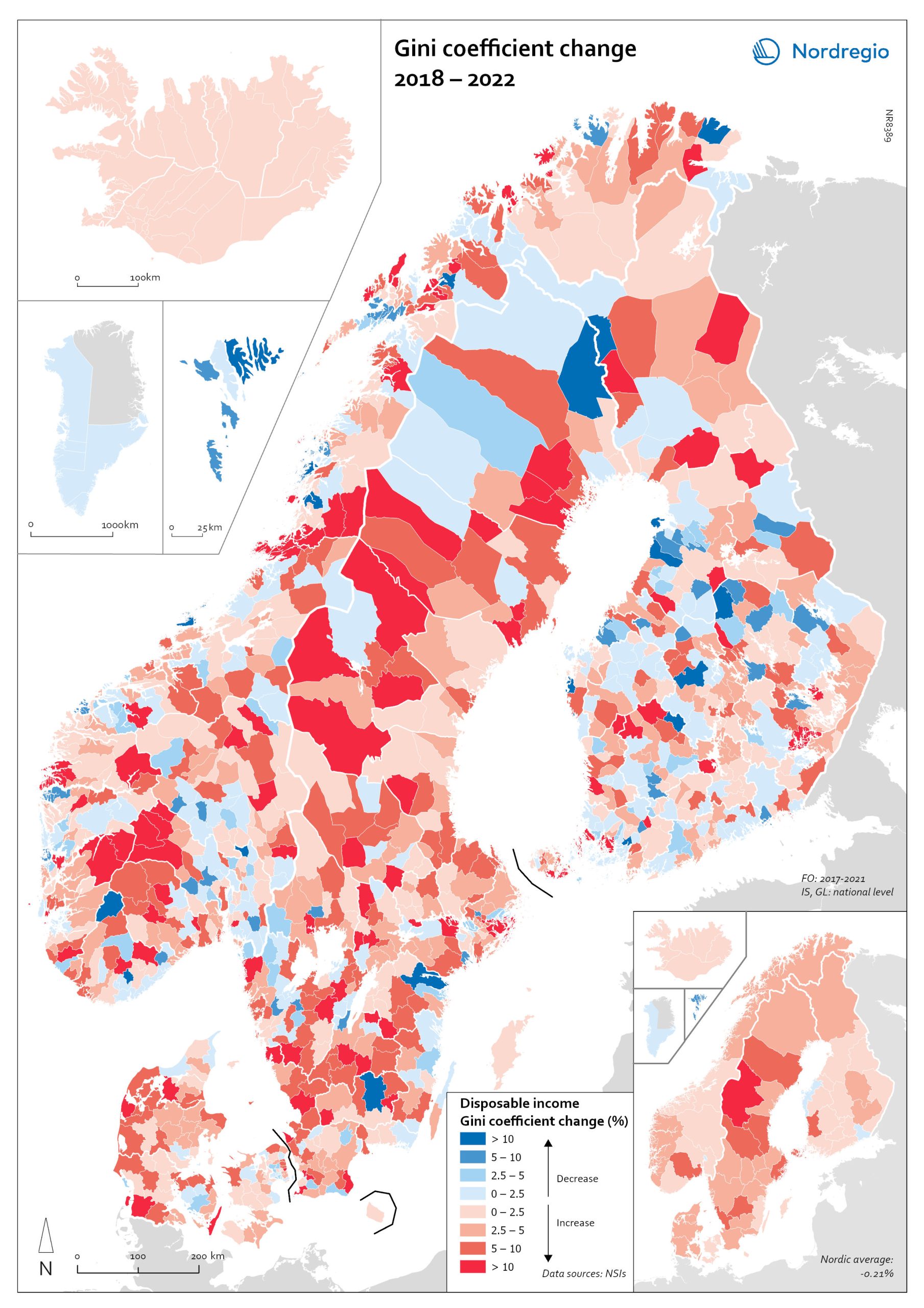

Gini coefficient change 2018-2022

This map shows the percentage change in the Gini coefficient between 2018 and 2022. The big map shows the change on municipal level and the big map at regional level. Blue shades indicate a decrease in income inequality, while red areas indicate an increase in income inequality The Gini coefficient index is one of the most widely used inequality measures. The index ranges from 0–1, where 0 indicates a society where everyone receives the same income, and 1 is the highest level of inequality, where one individual or group possesses all the resources in the society, and the rest of the population has nothing. The map illustrates significant variations in the change in income inequality across Nordic municipalities and regions. Between 2018 and 2022, income inequality increased in predominantly rural municipalities, notably in Jämtland, Gävleborg, Dalarna and Västerbotten in Sweden, as well as Telemark in Norway. For Denmark, the rise in inequality is mainly for the municipalities in Western Jutland. At the same time, approximately one third of municipalities in the Nordic Region experienced a decrease in income inequality during the same period, primarily in Finland and Åland. For example, in Finland, the distribution of inequality was more varied. This trend aligns with the ongoing narrowing of the household income gap observed in many Finnish municipalities since 2011, which is mainly attributed to the economic downturn of the early 2010s, as well as demographic shifts such as outmigration and ageing.

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

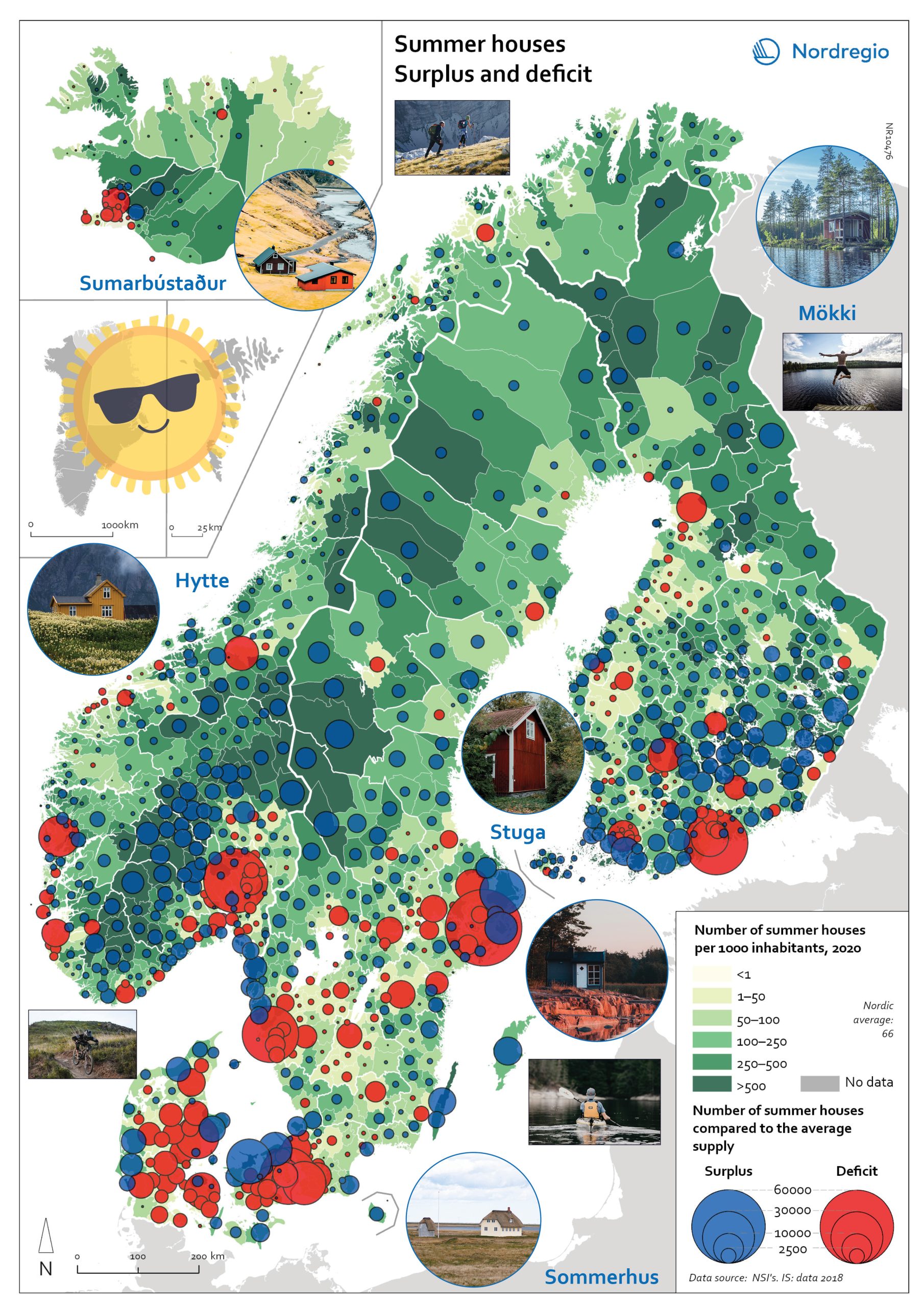

Gone missing: Nordic people!

Nordregio Summer Map 2022: Empty streets, closed restaurants – where is everyone? Nordic cities are about to quiet down as millions of people are logging out from work. But where do they go – Mallorca? Some yes, but the Nordic people are known for their nature-loving and private spirit, and most like to unwind in isolation. So, they head to their private paradises – to one of the 1.8 million summer houses around the Nordics, or as they would call them: sommerhus, stuga, hytte, sumarbústaður or mökki. The Nordregio Summer Map 2022 reveals the secret spots. The Finnish and Norwegians are most likely already packing their cars and leaving the cities: the highest supply of summer houses per inhabitant is found in Finland (92 summer houses per 1000 inhabitants) closely followed by Norway (82). The Swedish (59) Danish (40) and Icelandic (40) people seem to have more varied summer activities. There are large regional differences in the number of summer houses and the number of potential users – so not enough cabins where people would want them! And this is the dilemma Nordregio Summer Map 2022 shows in detail. Most people live in the larger urban areas while many summer houses are located in more remote and sparsely populated areas. The largest deficit of summer houses is found in Stockholm: with almost 1 million inhabitants, there is a need for 65,000 summer houses but the municipality has only 2,000 to offer! So, people living in Stockholm need to go elsewhere to find a summer house. The same goes for the other capital municipalities which have large deficits in summer houses: Oslo is missing 44,000, Helsinki 43,000, and Copenhagen 34,000. Fortunately, there are places that would happily accommodate these second-home searchers. Good news for Stockholm after all as the top-scoring municipality…

2022 June

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

Typology of regional internal net migration 2020-2021

The map presents a typology of internal net migration in regions by considering average annual internal net migration in 2020-2021 alongside the same figure for 2018-2019. The colours on the map correspond to six possible migration trajectories: Dark blue: Internal net in migration as an acceleration of an existing trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) Light blue: Internal net in migration but at a slower rate than previously (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Green: Internal net in migration as a new trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net out-migration compared to 2018-2019) Yellow: Internal net out migration as a new trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net in-migration compared to 2018-2019) Orange: Internal net out migration but at a slower rate than previously (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Red: Internal net out migration as a continuation of an existing trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019)

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

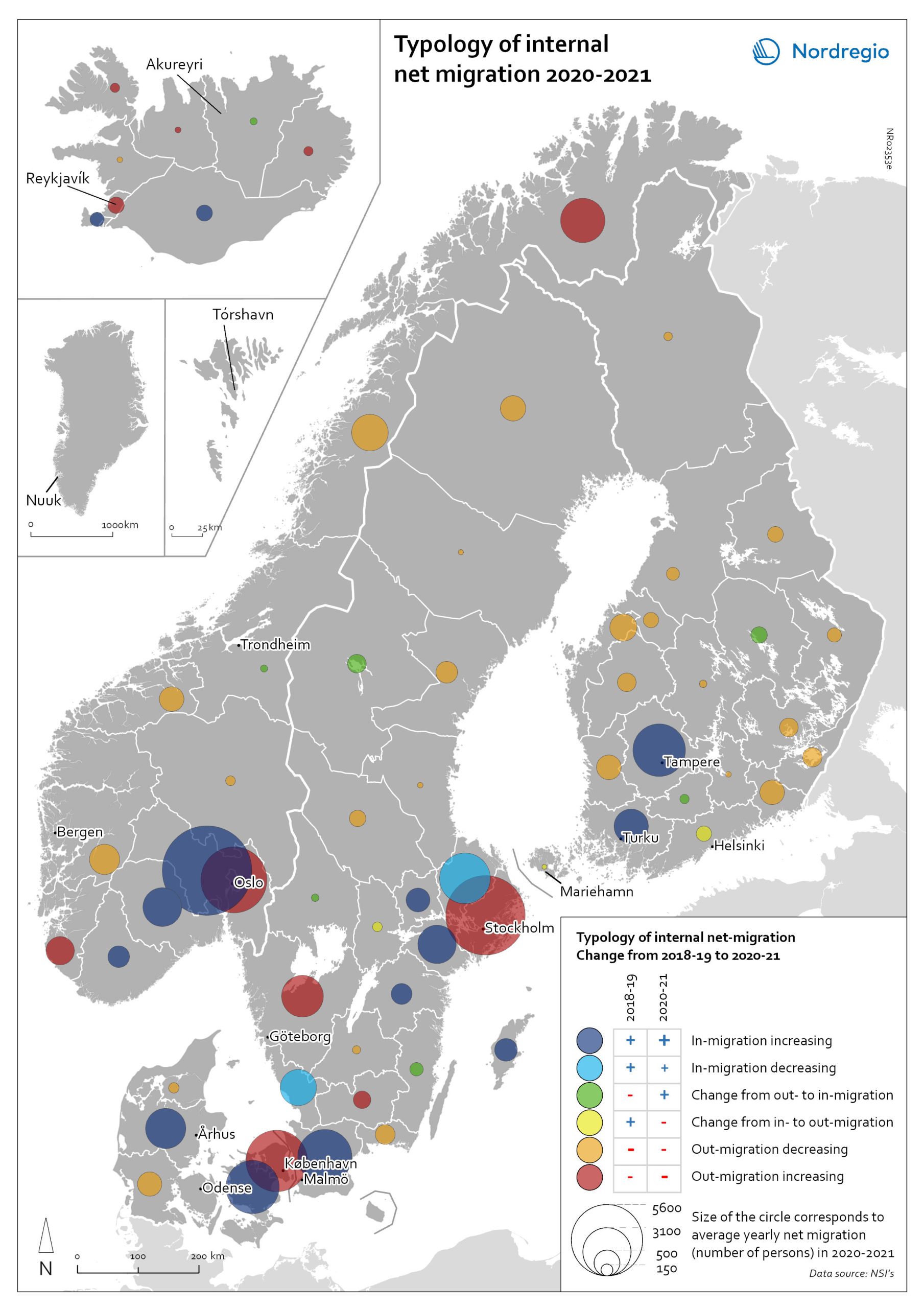

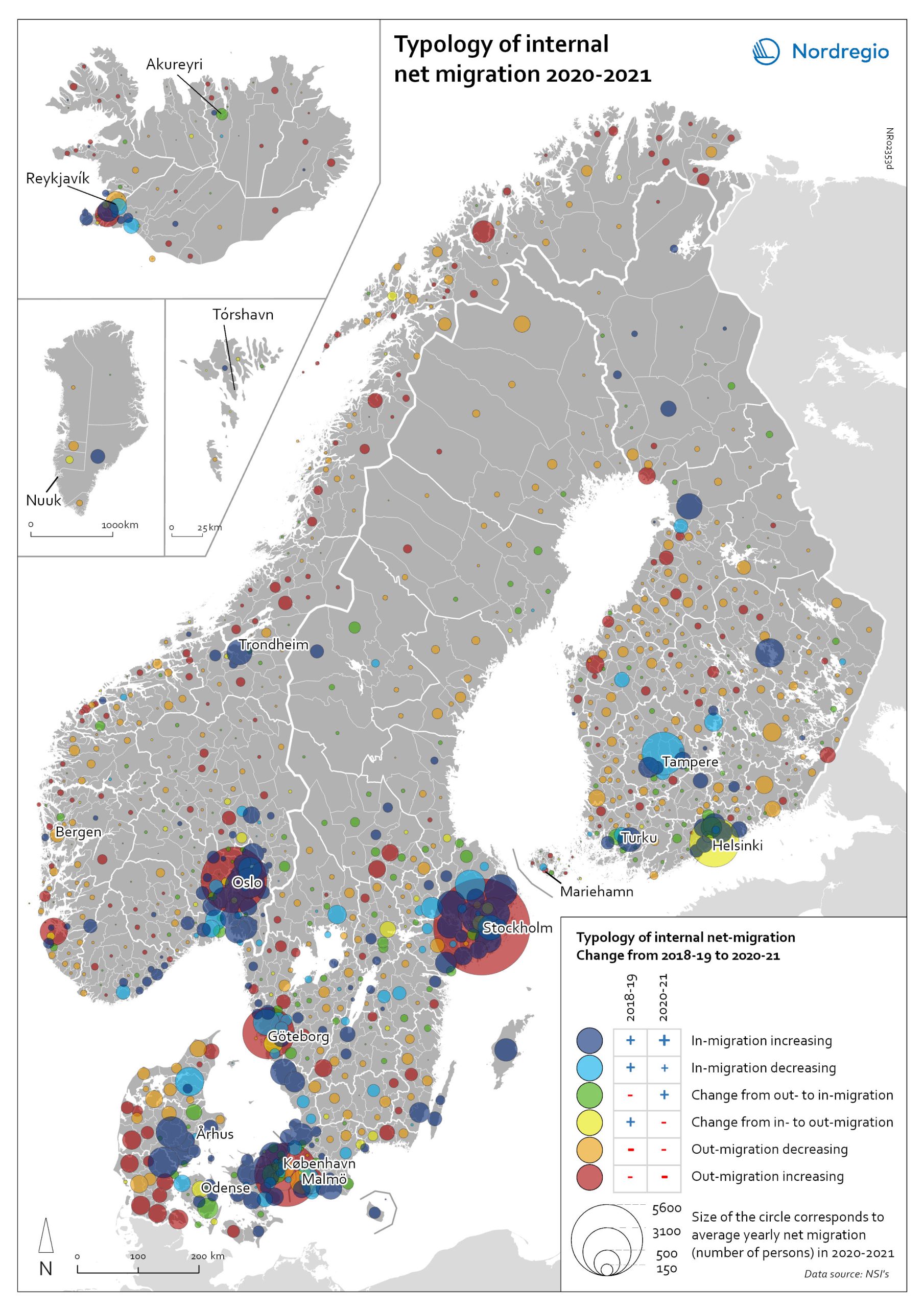

Typology of internal net migration 2020-2021

The map presents a typology of internal net migration by considering average annual internal net migration in 2020-2021 alongside the same figure for 2018-2019. The colours on the map correspond to six possible migration trajectories: Dark blue: Internal net in migration as an acceleration of an existing trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) Light blue: Internal net in migration but at a slower rate than previously (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Green: Internal net in migration as a new trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net out-migration compared to 2018-2019) Yellow: Internal net out migration as a new trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net in-migration compared to 2018-2019) Orange: Internal net out migration but at a slower rate than previously (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Red: Internal net out migration as a continuation of an existing trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) The patterns shown around the larger cities reinforces the message of increased suburbanisation as well as growth in smaller cities in proximity to large ones. In addition, the map shows that this is in many cases an accelerated (dark blue circles), or even new development (green circles). Interestingly, although accelerated by the pandemic, internal out migration from the capitals and other large cities was an existing trend. Helsinki stands out as an exception in this regard, having gone from positive to negative internal net migration (yellow circles). Similarly, slower rates of in migration are evident in the two next largest Finnish cities, Tampere and Turku (light blue circles). Akureyri (Iceland) provides an interesting example of an intermediate city which began to attract residents during the pandemic despite experiencing internal outmigration prior. From a rural perspective there are…

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

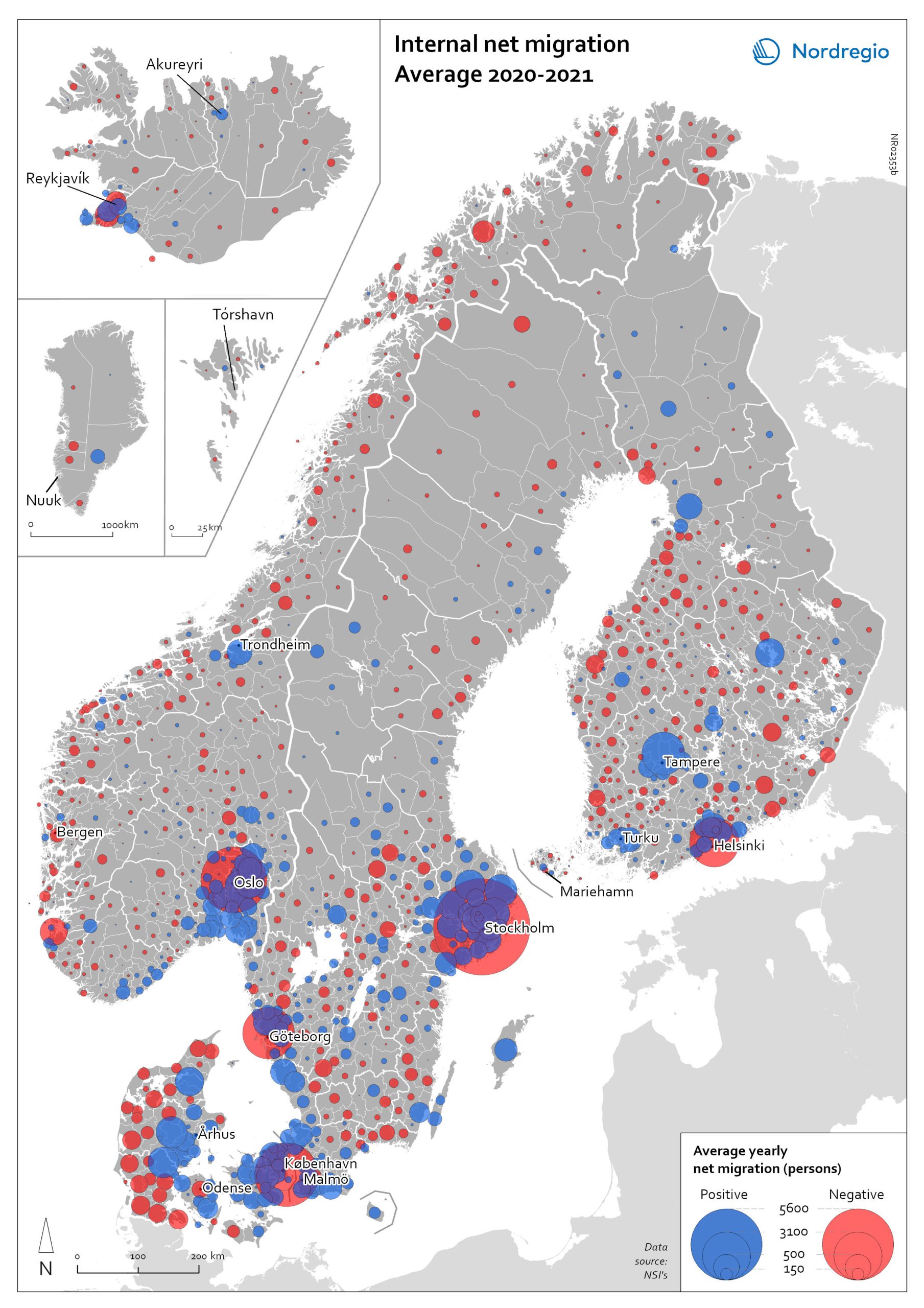

Internal net migration 2020-2021

The map shows the average internal net migration in 2020 and 2021 for Nordic municipalities. Blue dots indicate positive internal net migration (more people moving in than out) and red dots indicate negative internal net migration (more people moving out than in), while the size of the dots represents the extent of the positive or negative trend. Internal migration refers to a change of address within the same country. The map shows substantial outmigration from the Nordic capitals, as well as from Gothenburg and Malmö in Sweden. Alongside increased suburbanisation, the map also provides some evidence of growth in medium-sized cities and smaller cities within commuting distance of larger cities.

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

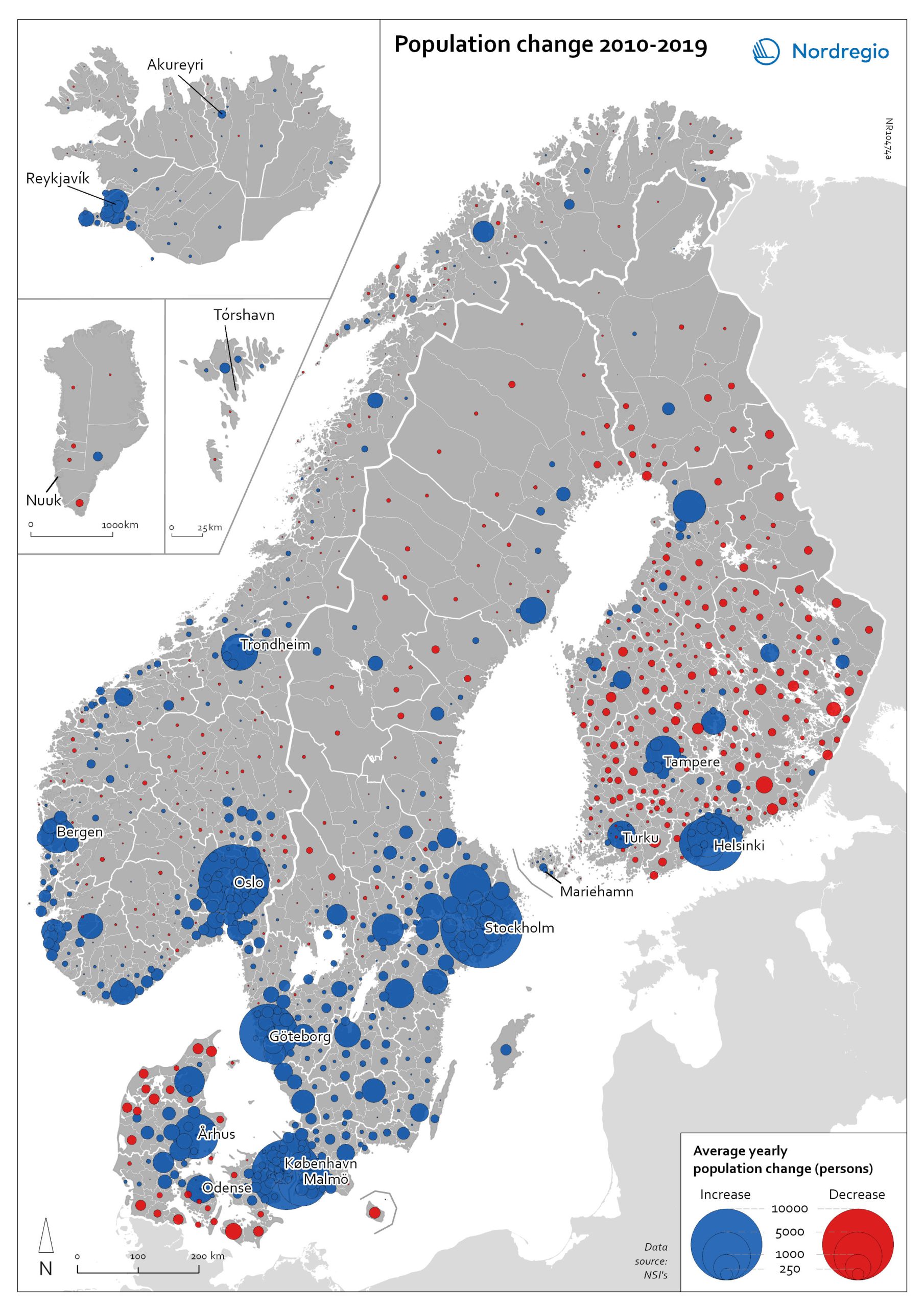

Population change 2010-2019

The map shows the type (positive or negative) and size of population change from 2010 to 2019 in all nordic municipalities. In Finland, Denmark, and Greenland there is a clear pattern of population growth in and around the larger cities and population decline in rural areas. Geographical and administrative differences mean that a much larger number of rural municipalities in Finland are dealing with population decline. Sweden experienced substantial population growth between 2010 and 2019, primarily due to high levels of international immigration. As a result, many rural areas also experienced population growth, particularly in the south of Sweden. However, in the more sparsely populated municipalities in the north of Sweden, the pattern is somewhat similar to that observed in Denmark and Finland, albeit with population decline in lower absolute numbers. Both Iceland and the Faroe Islands experienced substantial growth of their tourism industries within the period. This enabled some rural areas to maintain or even grow their populations. Norway exhibits more balanced population development in general, with a mix of population growth and decline in rural areas throughout the country.

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

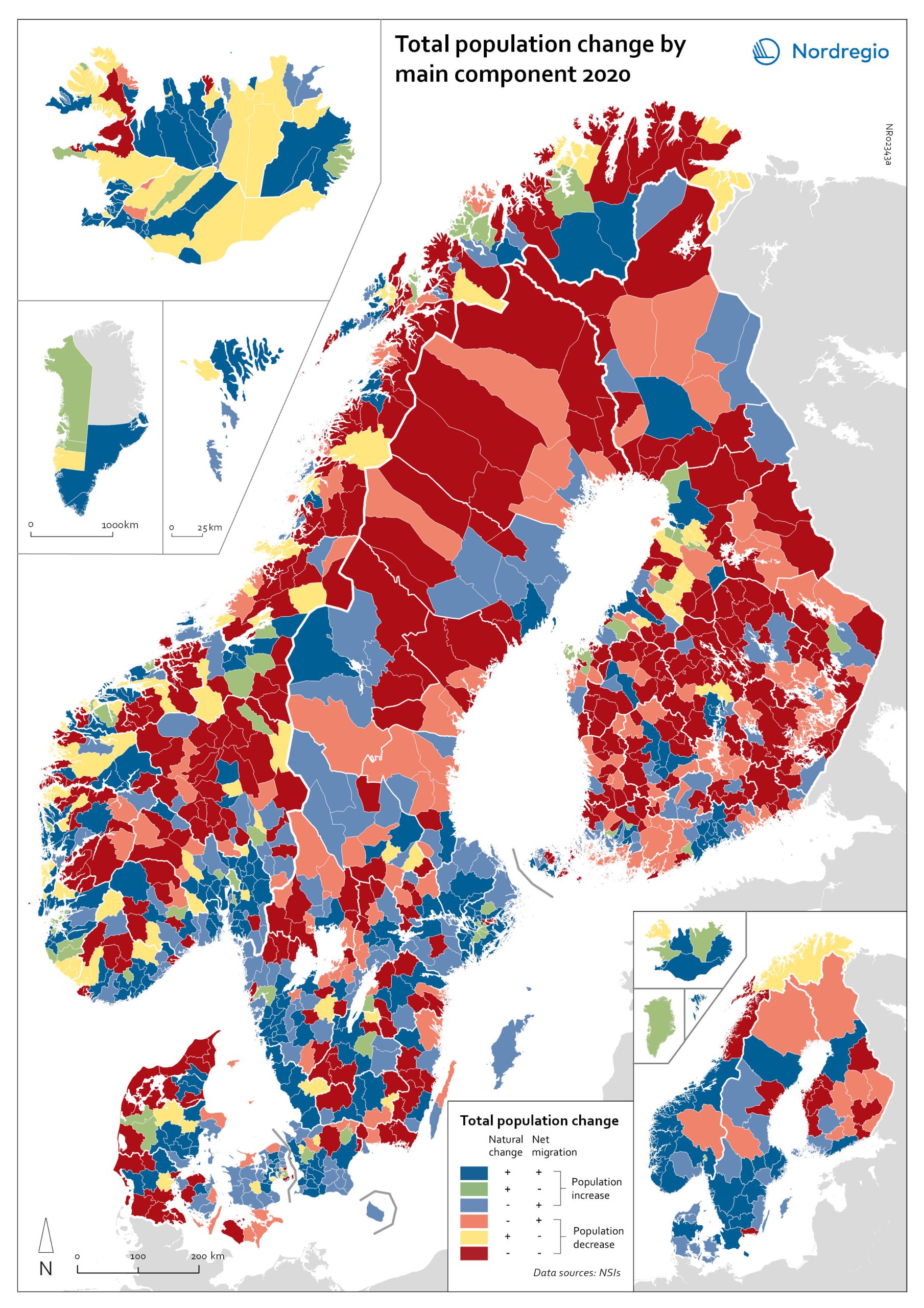

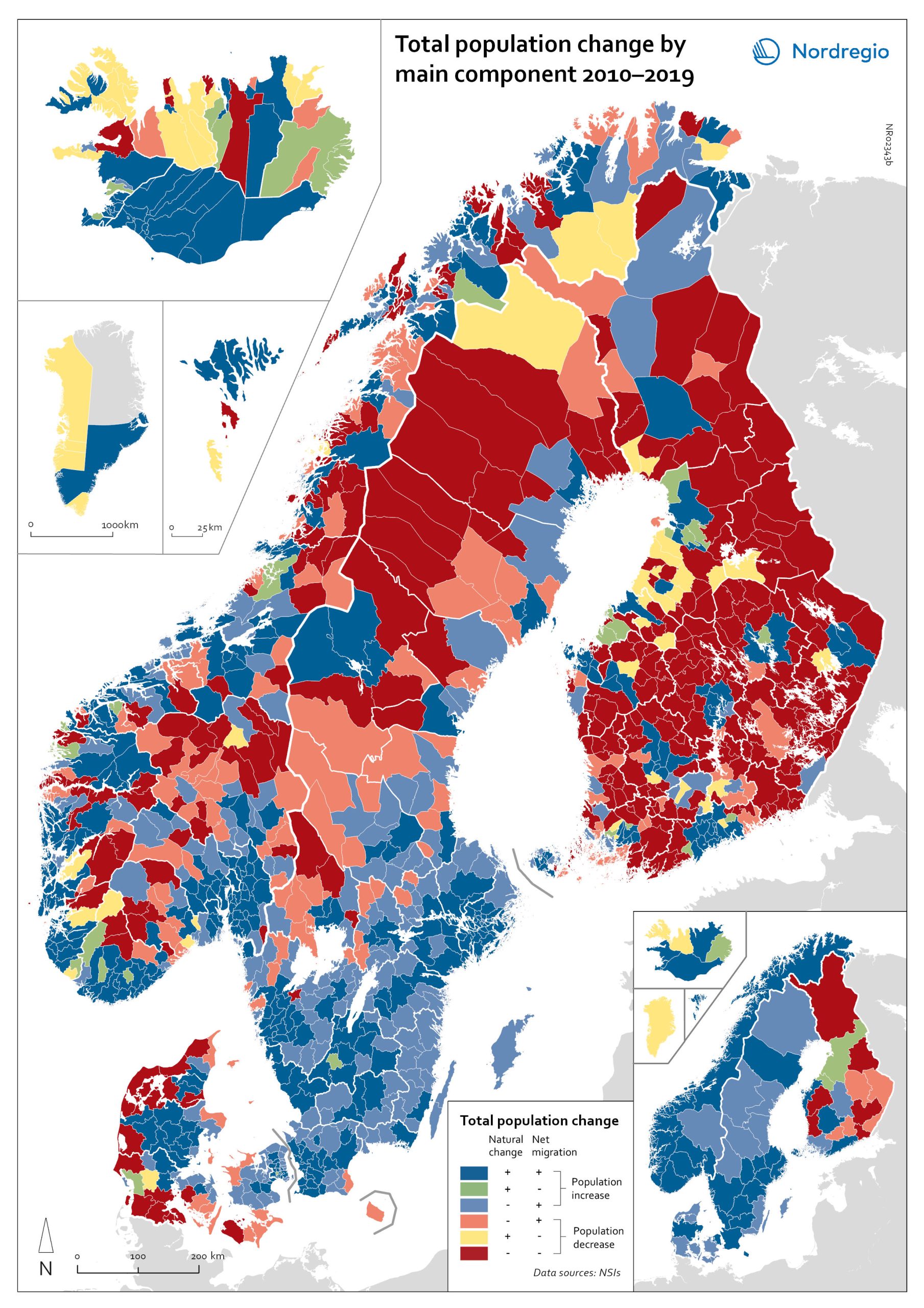

Population change by component 2020

The map shows the population change by component 2020. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2010-2019. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Population change by component 2010-2019

The map shows the population change by component 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2020. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

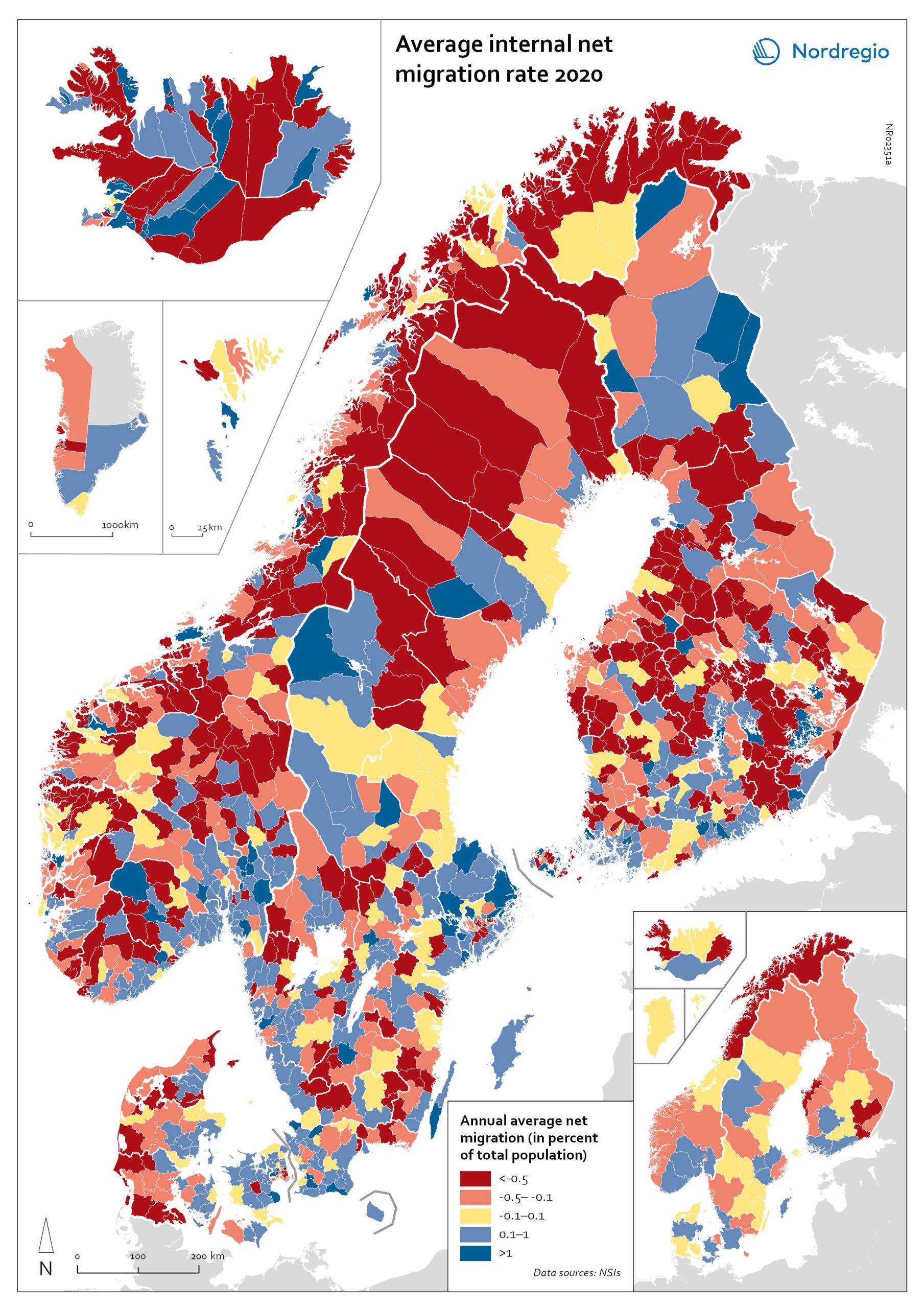

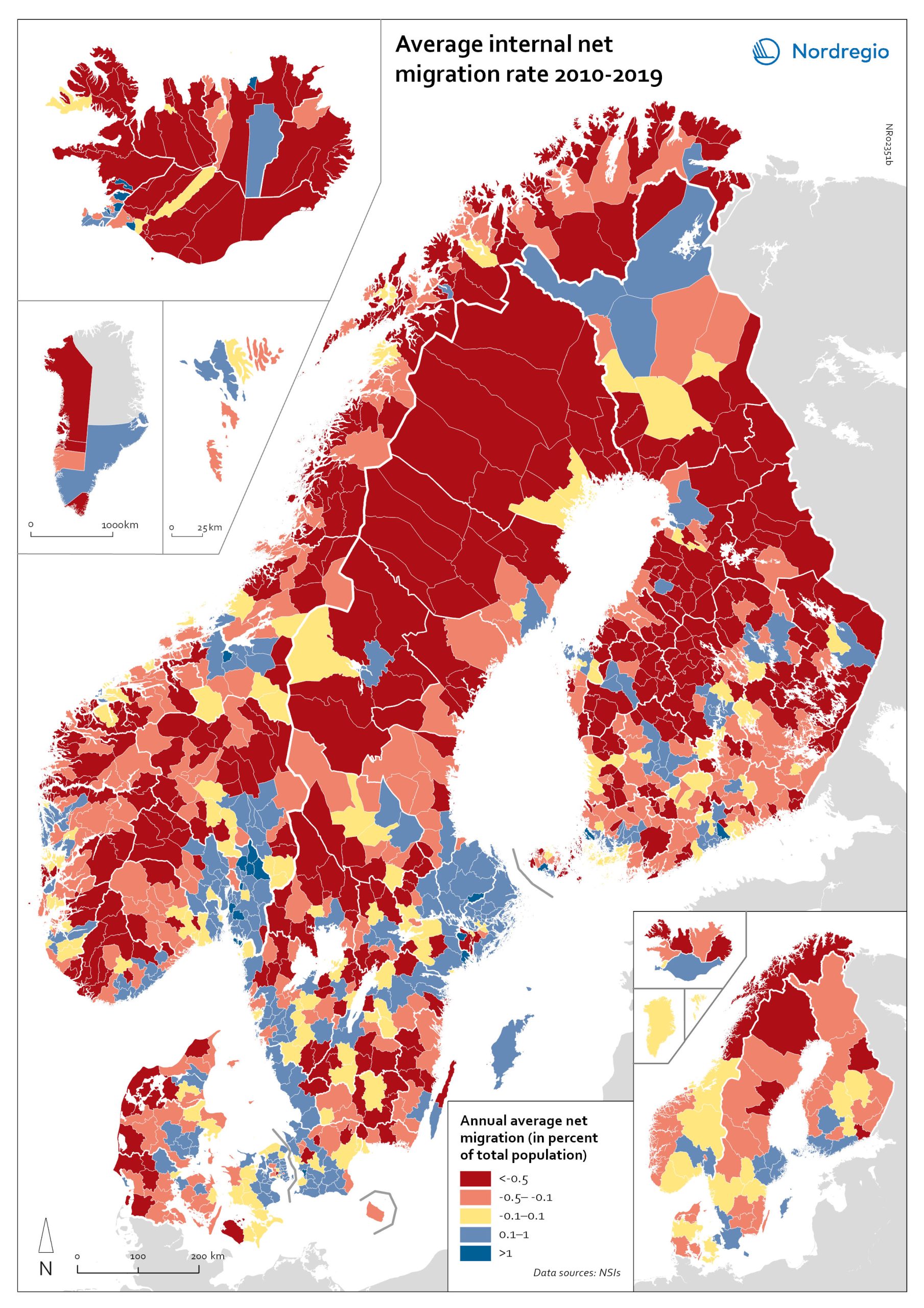

Net internal migration rate 2020

The map shows the internal net migration in 2020. The map is related to the same map showing net internal migration in 2010-2019. The maps show several interesting patterns, suggesting that there may be an increasing trend towards urban-to-rural countermigration in all the five Nordic countries because of the pandemic. In other words, there are several rural municipalities – both in sparsely populated areas and areas close to major cities – that have experienced considerable increases in internal net migration. In Finland, for instance, there are several municipalities in Lapland that attracted return migrants to a considerable degree in 2020 (e.g., Kolari, Salla, and Savukoski). Swedish municipalities with increasing internal net migration include municipalities in both remote rural regions (e.g., Åre) and municipalities in the vicinity of major cities (e.g., Trosa, Upplands-Bro, Lekeberg, and Österåker). In Iceland, there are several remote municipalities that have experienced a rapid transformation from a strong outflow to an inflow of internal migration (e.g., Ásahreppur, Tálknafjarðarhreppurand, and Fljótsdalshreppur). In Denmark and Norway, there are also several rural municipalities with increasing internal net migration (e.g., Christiansø in Denmark), even if the patterns are somewhat more restrained compared to the other Nordic countries. Interestingly, several municipalities in capital regions are experiencing a steep decrease in internal migration (e.g., Helsinki, Espoo, Copenhagen and Stockholm). At regional level, such decreases are noted in the capital regions of Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Stockholm. At the same time, the rural regions of Jämtland, Kalmar, Sjælland, Nordjylland, Norðurland vestra, Norðurland eystra and Kainuu recorded increases in internal net migration. While some of the evolving patterns of counterurbanisation were noted before 2020 for the 30–40 age group, these trends seem to have been strengthened by the pandemic. In addition to return migration, there may be a larger share of young adults who decide to…

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Net internal migration rate, 2010-2019

The map shows the annual average internal net migration in 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing net internal migration in 2020. The maps show several interesting patterns, suggesting that there may be an increasing trend towards urban-to-rural countermigration in all the five Nordic countries because of the pandemic. In other words, there are several rural municipalities – both in sparsely populated areas and areas close to major cities – that have experienced considerable increases in internal net migration. In Finland, for instance, there are several municipalities in Lapland that attracted return migrants to a considerable degree in 2020 (e.g., Kolari, Salla, and Savukoski). Swedish municipalities with increasing internal net migration include municipalities in both remote rural regions (e.g., Åre) and municipalities in the vicinity of major cities (e.g., Trosa, Upplands-Bro, Lekeberg, and Österåker). In Iceland, there are several remote municipalities that have experienced a rapid transformation from a strong outflow to an inflow of internal migration (e.g., Ásahreppur, Tálknafjarðarhreppurand, and Fljótsdalshreppur). In Denmark and Norway, there are also several rural municipalities with increasing internal net migration (e.g., Christiansø in Denmark), even if the patterns are somewhat more restrained compared to the other Nordic countries. Interestingly, several municipalities in capital regions are experiencing a steep decrease in internal migration (e.g., Helsinki, Espoo, Copenhagen and Stockholm). At regional level, such decreases are noted in the capital regions of Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Stockholm. At the same time, the rural regions of Jämtland, Kalmar, Sjælland, Nordjylland, Norðurland vestra, Norðurland eystra and Kainuu recorded increases in internal net migration. While some of the evolving patterns of counterurbanisation were noted before 2020 for the 30–40 age group, these trends seem to have been strengthened by the pandemic. In addition to return migration, there may be a larger share of young adults who…

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

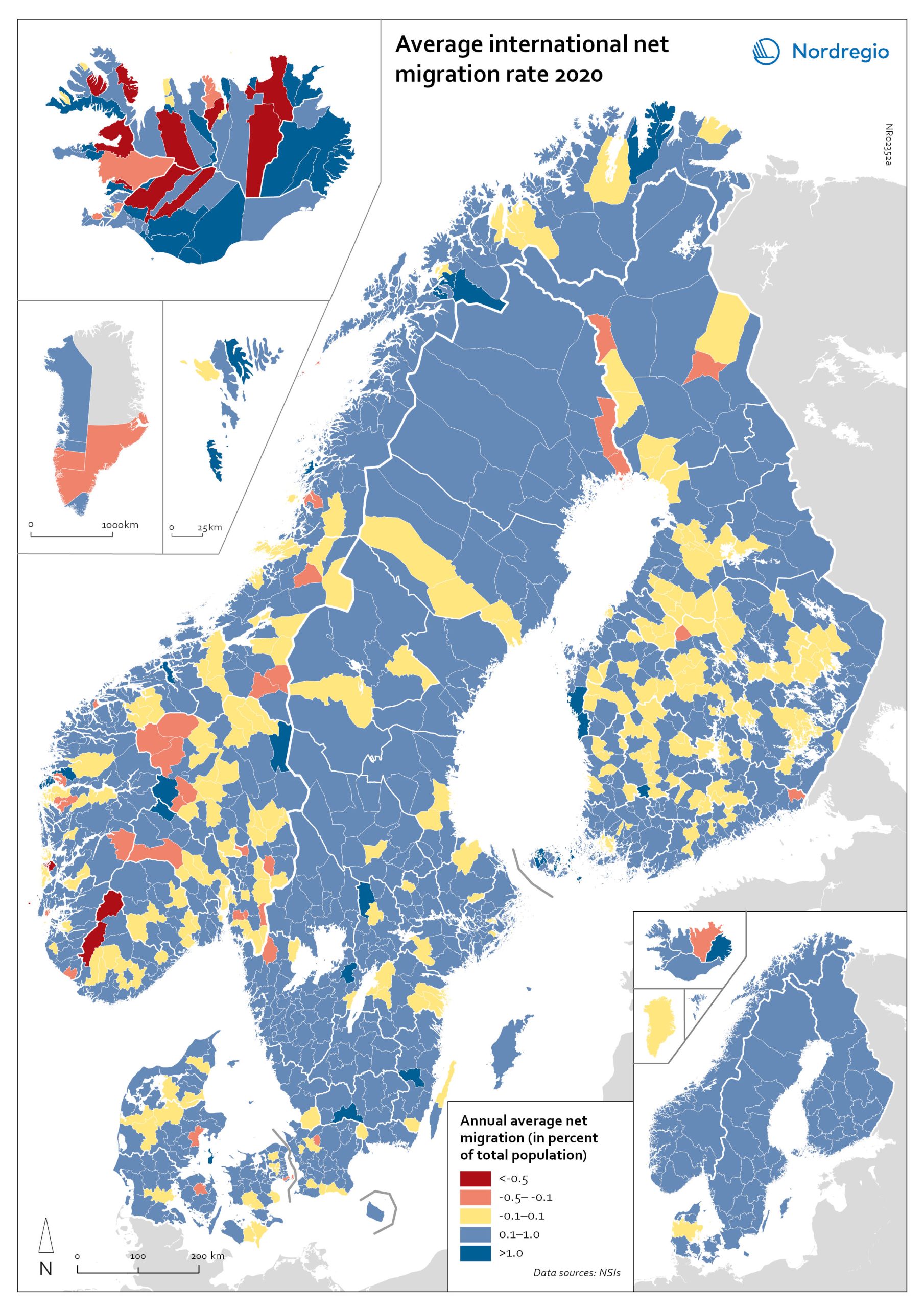

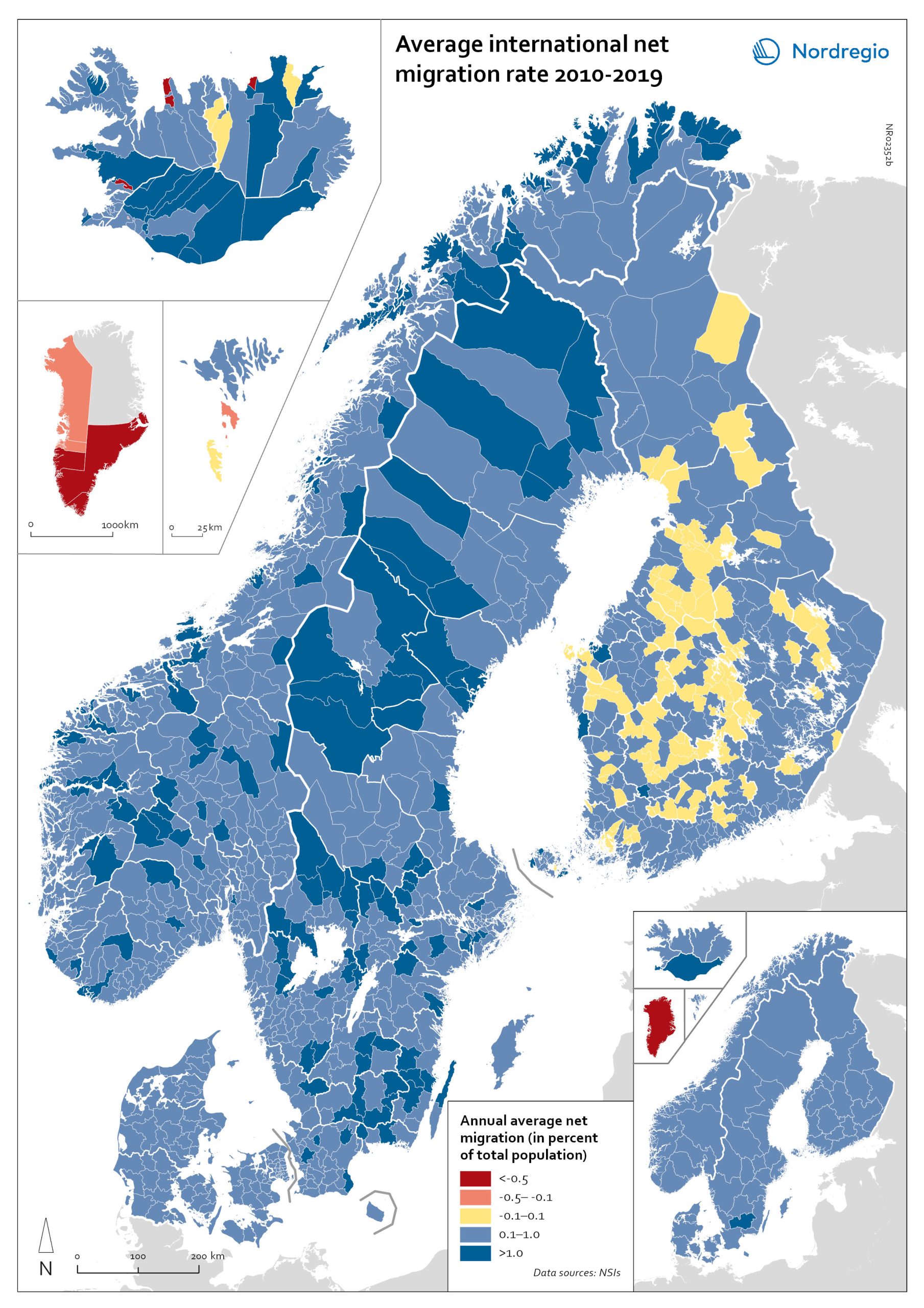

Net international migration rate, 2020

The map shows the international net migration in 2020. The map is related to the same map showing net migration in 2010-2019. At regional level, there are only minor changes between the net migration in 2010-2019 and 2020. All regions of Norway, all regions of Sweden except Gotland and Uppsala, and the regions of Österbotten in Finland, Midtjylland in Denmark and Norðurland eystra in Iceland experienced a slight decrease in international net migration I 2020 compared to 2010-2019. There is a more marked increase in net migration in the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the region of Norðurland vestra in Iceland, and a slight increase in the region of Austurland in Iceland. At municipal level, the maps show more changing patterns. In Denmark, Norway and Sweden, several municipalities – both in the capital, intermediate, and rural regions – had lower levels of international net migration in 2020 compared to 2010-2019. In Iceland and Finland, the picture is more balanced, with some municipalities showing a decrease, others an increase. In the Faroe Islands and Greenland, several municipalities/regions had an increase in international net migration.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Net international migration rate, 2010–2019

The map shows the annual average international net migration from 2010 to 2019. The map is related to the same map showing net migration in 2020. At regional level, there are only minor changes between the net migration in 2010-2019 and 2020. All regions of Norway, all regions of Sweden except Gotland and Uppsala, and the regions of Österbotten in Finland, Midtjylland in Denmark and Norðurland eystra in Iceland experienced a slight decrease in international net migration I 2020 compared to 2010-2019. There is a more marked increase in net migration in the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the region of Norðurland vestra in Iceland, and a slight increase in the region of Austurland in Iceland. At municipal level, the maps show more changing patterns. In Denmark, Norway and Sweden, several municipalities – both in the capital, intermediate, and rural regions – had lower levels of international net migration in 2020 compared to 2010-2019. In Iceland and Finland, the picture is more balanced, with some municipalities showing a decrease, others an increase. In the Faroe Islands and Greenland, several municipalities/regions had an increase in international net migration.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

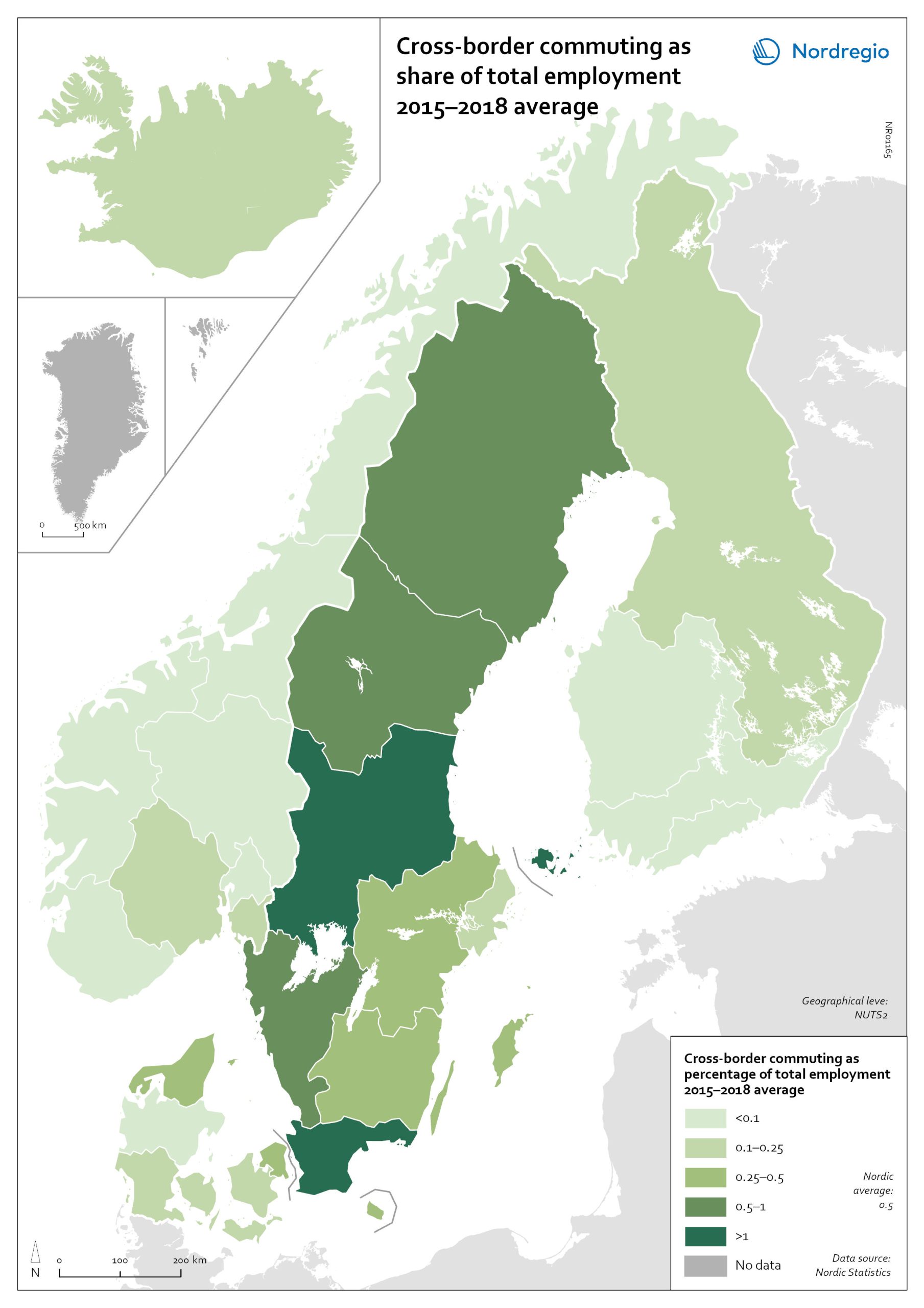

Cross-border commuting as share of employment

The map illustrates the average share of employees who commuted to another Nordic country between between 2015 and 2018 in Nordic regions (NUTS 2). Between 2015 and 2018, an average of approximately 49,000 people held a job in a Nordic country in which they were not residents. This indicates that, on average, 0.5% of the Nordic working-age population commuted to a job in another Nordic country. This is below the EU27 average of 1%, with the highest numbers found in Slovakia (5.1%), Luxembourg (2.8%) and Estonia (2.6%). Some of these people cross borders daily. Others work in another country by means of remote working combined with occasional commuting across borders. Within the Nordic Region, the largest cross-border commuter flows are in the southernmost parts of Sweden, regions in the middle of Sweden and in Åland, where more than 1% of the working population commutes to another Nordic country. However, there may be individual municipalities where cross-border commuting is substantially higher. For example, the employment rate in Årjäng Municipality, Sweden, increases by 15 percentage points when cross-border commuting is taken into account. These municipalities are not reflected on NUTS 2 level when averages are calculated. In terms of absolute numbers in 2015, the highest numbers of commuters were from Sweden: Sydsverige (16,543), Västsverige (7,899) and Norra Mellansverige (6,890). The highest number of commuters from a non-Swedish region were from Denmark’s Hovedstaden (2,583). Due to legislative barriers regarding the exchange of statistical data on cross-border commuting between the Nordic countries, more recent data is not available.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

Major immigration flows to the Nordic Region from 2010 to 2019

The map shows annual average immigration flows above 3,000 people, and the growing diversity in their countries of origin Sweden and Denmark, in particular, experienced large inflows from non-Nordic countries during the period 2010-2019, with Sweden standing out as the Nordic country with by far the largest immigrant in-flows. A large portion of these arrivals were from war-torn Syria (an annual average of almost 15,000), followed by Poland (approximately 4,500), United Kingdom, Iraq, India and Iran (around 4,000 each). Denmark experienced a smaller number of inflows above 3,000 people, compared to Sweden. The largest non-Nordic inflows to Denmark were around 5,000 people (per sending country) and included migrants from the U.S., Germany, Romania and Poland. For Norway, large non-Nordic in-flows were limited to Lithuania and Poland. Similarly, Finland had only one major inflow, from Estonia.

2021 December

- Migration

- Nordic Region

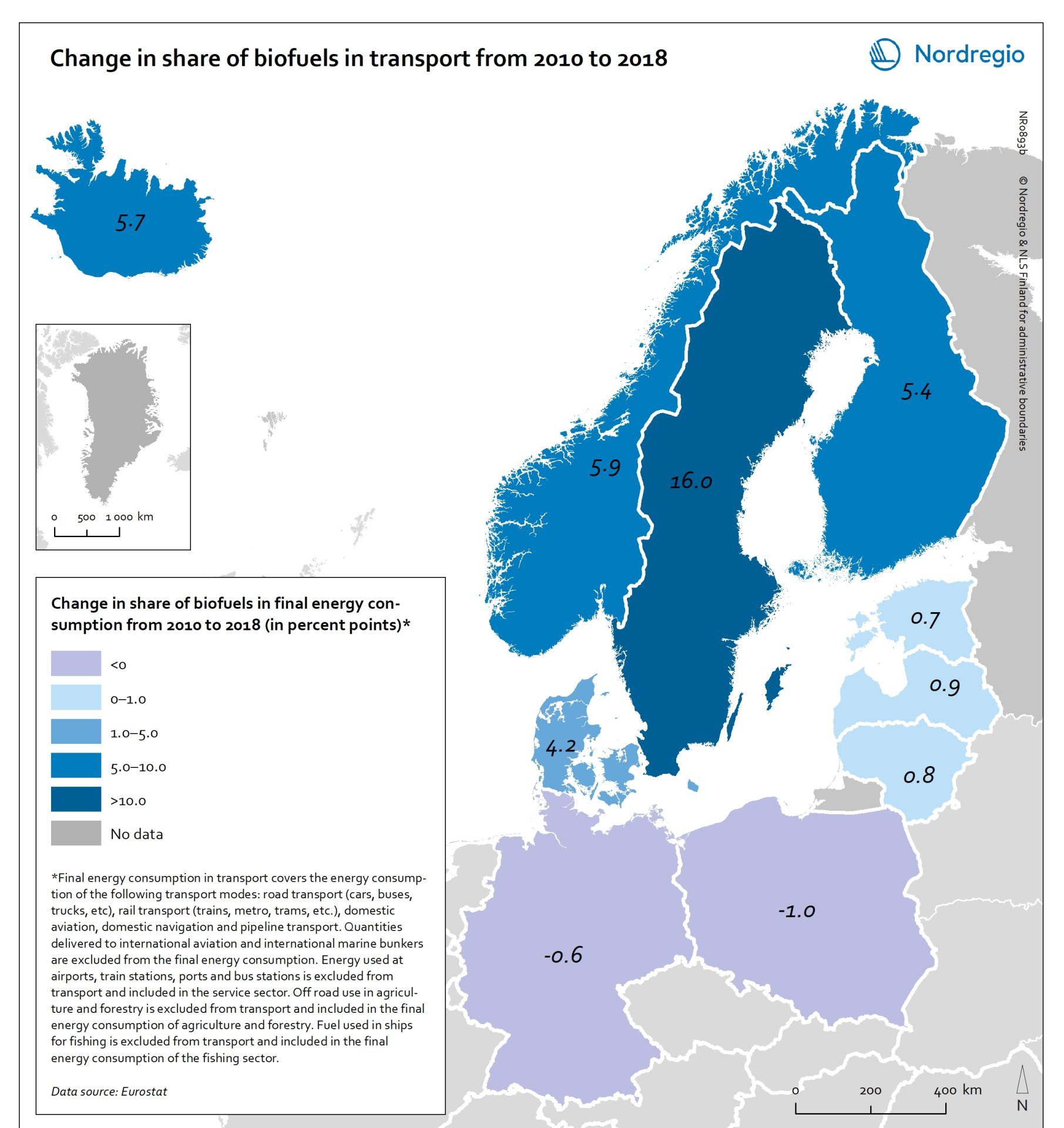

Change in share of biofuels in transport from 2010 to 2018

This map shows change in share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region from 2010 to 2018. Even though a target for greater use of biofuels has been EU policy since the Renewable Energy and Fuel Quality Directives of 2009, development has been slow. The darker shades of blue on the map represent higher increase, and the lighter shades of blue reflect lower increase. The lilac color represent decrease. The Baltic Sea represents a divide in the region, with countries to the north and west experiencing growth in the use of biofuels for transport in recent years. Sweden stands out (16 per cent growth), while the other Nordic countries has experienced more modest increase. In the southern and eastern parts of the region, the use of biofuels for transport has largely stagnated. Total biofuel consumption for transport has risen more than the figure indicates due to an increase in transport use over the period.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport