21 Maps

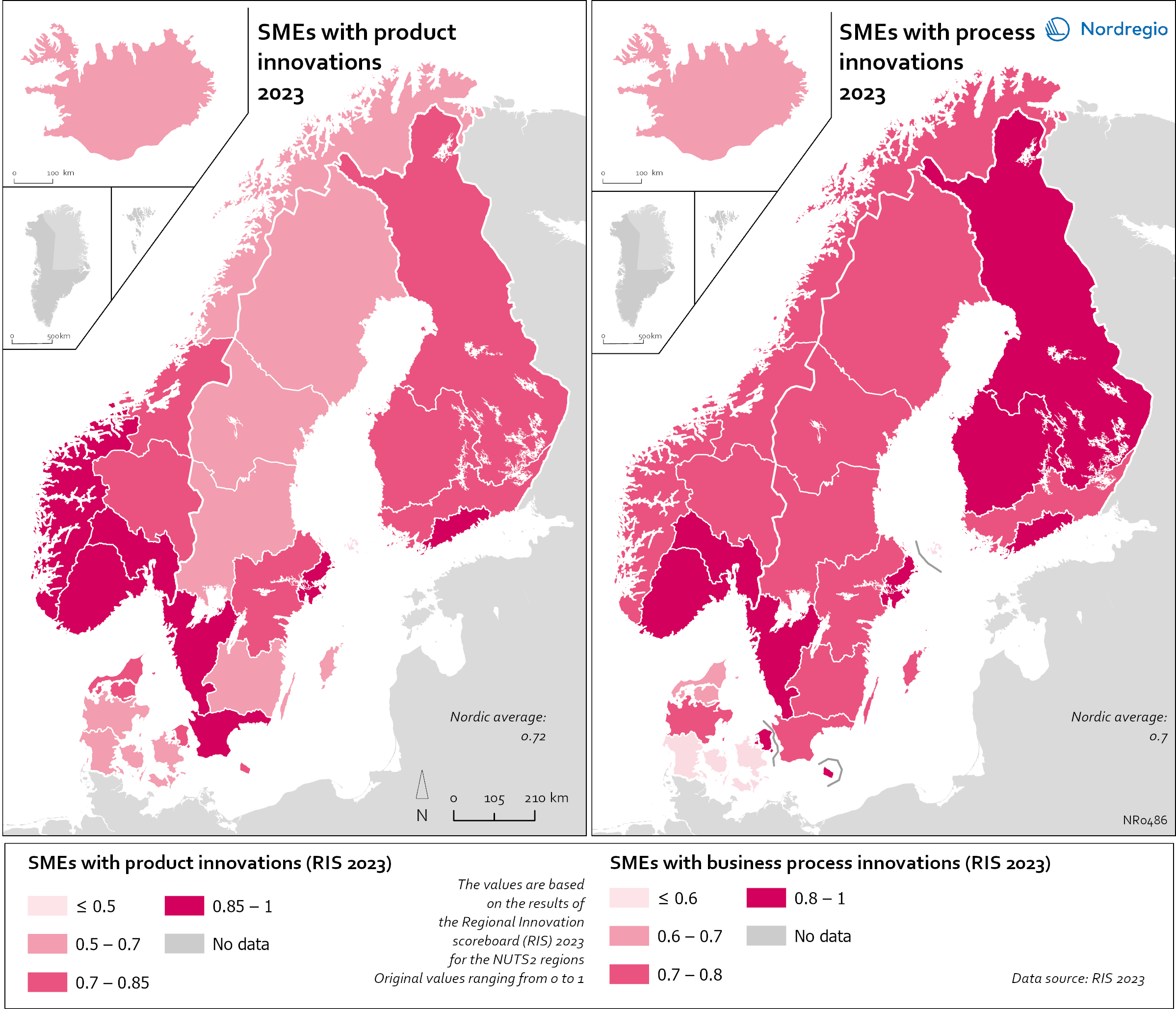

Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) with product and business process innovation in 2023

These maps depicts Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) with product innovation (left map) and process innovation (right map) in 2023. The data is displayed at the NUTS2 level and the data comes from the Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023. The left map depicts SMEs introducing product innovations as a percentage of SMEs in the Nordic regions, calculated as the share of SMEs who introduced at least one product innovation. The values for the map are normalised from 0–10. In this context, a product innovation is defined as the market introduction of a good or service that is new or significantly improved with respect to its capabilities, user-friendliness, components, or sub-systems. Rural regions tend to have lower levels of SMEs with product innovations, while urban regions have the highest levels. In 2023, Åland (0.235) had the lowest number of SMEs with product innovations in the Nordic Region, while Oslo had the highest (1.0). Etelä-Suomi and Stockholm regions were slightly behind, with 0.954 and 0.948, respectively. In Denmark, the leading regions were the Capital Region (Hovedstaden) and Northern Jutland (Nordjylland), with 0.719 and 0.715, respectively. Southern Denmark (Syddanmark) had the lowest level in Denmark, at 0.545. In Norway, the lowest value was in Northern Norway (Nord-Norge), 0.67, while in Sweden it was Middle Norrland (Mellersta Norrland), with 0.53. Taken as an average across the Nordic countries, Norway has a significantly higher number of SMEs with product innovations than the other countries. The right map shows the share of SMEs introducing at least one business-process innovation, which includes process, marketing, and organisational innovations. In general, Nordic SMEs are more likely to innovate in products rather than processes. The highest shares of process-innovating SMEs are found in most of the Finnish regions ranging from 0,79 in Länsi-Suomi to 0,91 in Etelä-Suomi, except of Åland…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

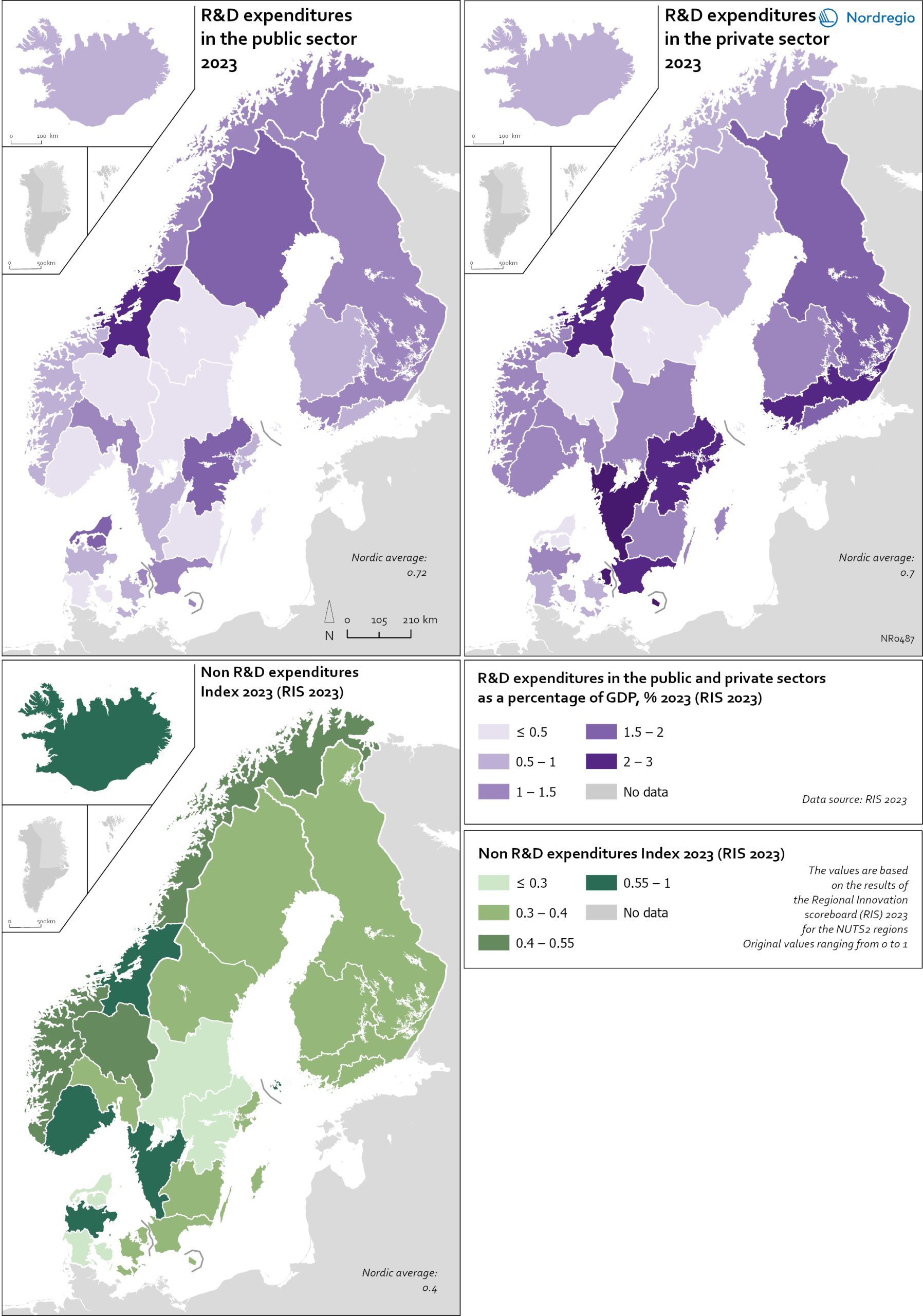

R&D and non-R&D expenditures in the public and private sector

These maps shows the expenditure on Research and Development (R&D) in the public and business sectors as a percentage of regional GDP, along with non-R&D innovation expenditure in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as a percentage of turnover. Together, these metrics offer a comprehensive understanding of the innovation landscape and provide insights into governments’ and higher education institutions’ commitment to foundational research, as well as the competitiveness and dynamism of the business environment and SMEs’ innovation capacity. By considering investment in both R&D and non-R&D activities, these indicators illustrate a broad spectrum of innovation drivers, from basic research to market-driven initiatives, and underscore the diverse pathways through which innovation fosters economic growth and social progress First, the top left map showcases R&D expenditure in the public sector as a percentage of GDP in the Nordic countries in 2023. In that year, the European level of R&D expenditure in the public sector, as a percentage of GDP, was 0.78%. By comparison, the Nordic average was 0.9%. While the more urban regions, in general, lead the Nordic regions, this is not always the case, as shown by the variation between the frontrunners. The leading region is Trøndelag (including Norway’s third-largest city, Trondheim), with 2.30% of regional GDP. It is in third place in the EU as a whole. The next regions are Övre Norrland with 1.77%, Northern Jutland with 1.54%, Östra Mellansverige with 1.52%, and Hovedstaden with 1.49%. A common feature of most of the top-ranking regions is that they host universities and other higher education institutions known for innovation practices. Most Nordic regions have not seen significant increases or decreases in public R&D spending between 2016 and 2023. The top right map focuses on the private sector’s investment in research and development activities and depicts R&D expenditure in the business sector…

2025 April

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

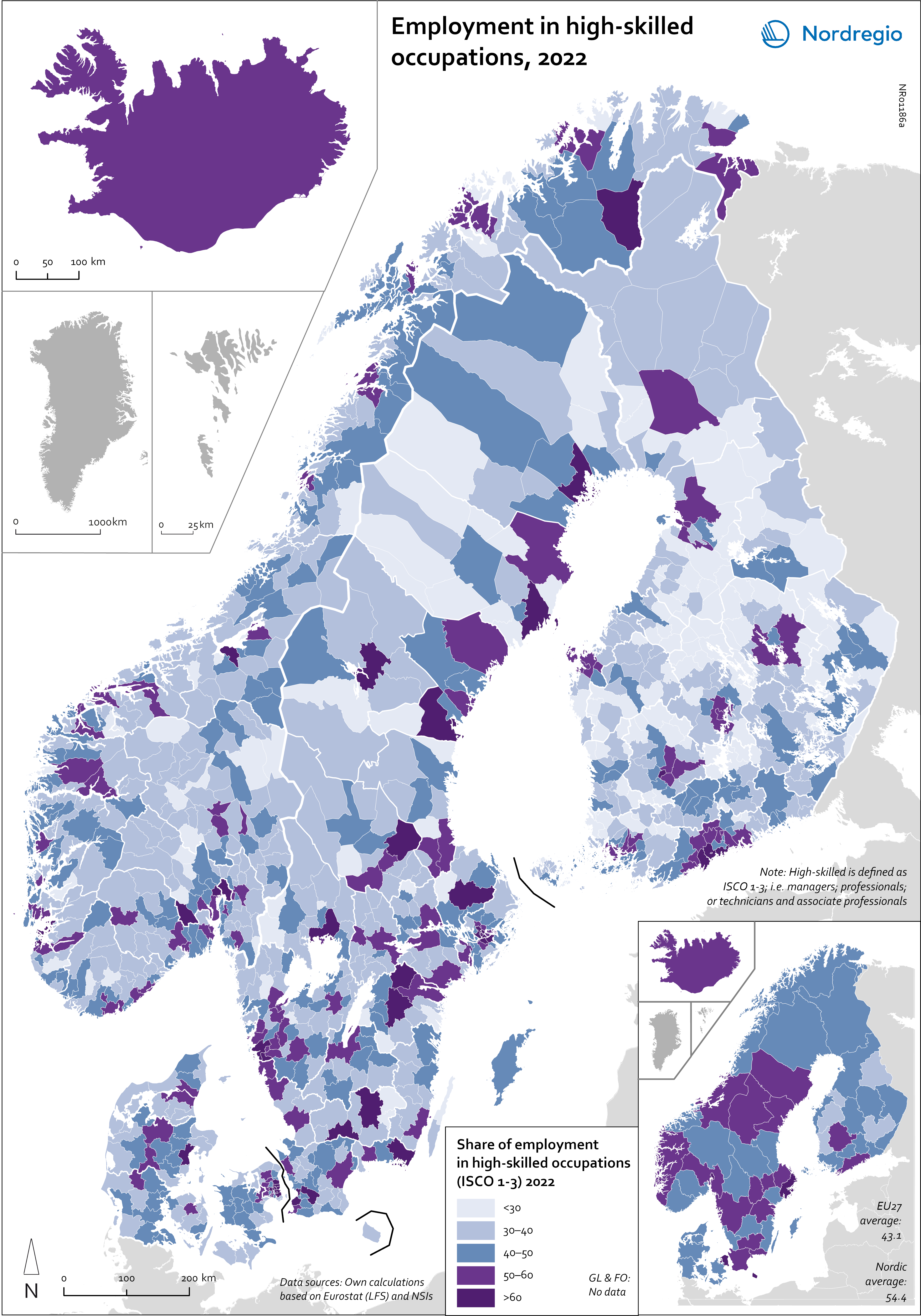

Employment in high-skilled occupations 2022

This map displays the share of high-skilled workers as a share of the total number of workers in Nordic municipalities (big map) and regions (small map). “High-skilled workers” is here defined as group 1-3 (Managers, Professionals and Techinicians/associated professionals) of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). For Iceland national data is used. The EU average of high-skilled workers is 43%, and the Nordic countries are at the top of the rankings – 49.5% in Finland, 51.1% in Denmark, 54.2% in Norway, 54.5% in Iceland and 58.9% in Sweden. On a regional level, the highest share is in the capitals and bigger cities, such as Stockholm (72%), Oslo (71%), Hovedstaden (Copenhagen) (60%), Uppsala (60%) and Uusima (Helsinki) (59%). The lowest shares are in the Finnish regions of EteläPohjanmaa, Keski-Pohjanmaa, Satakunta and Etelä-Savo (less than 40%). However, this does not necessarily mean that employers will have a greater chance of successfully recruiting high-skilled workers in the future, partly because those in this group already have jobs and partly due to generally lower investments in education.

2025 April

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

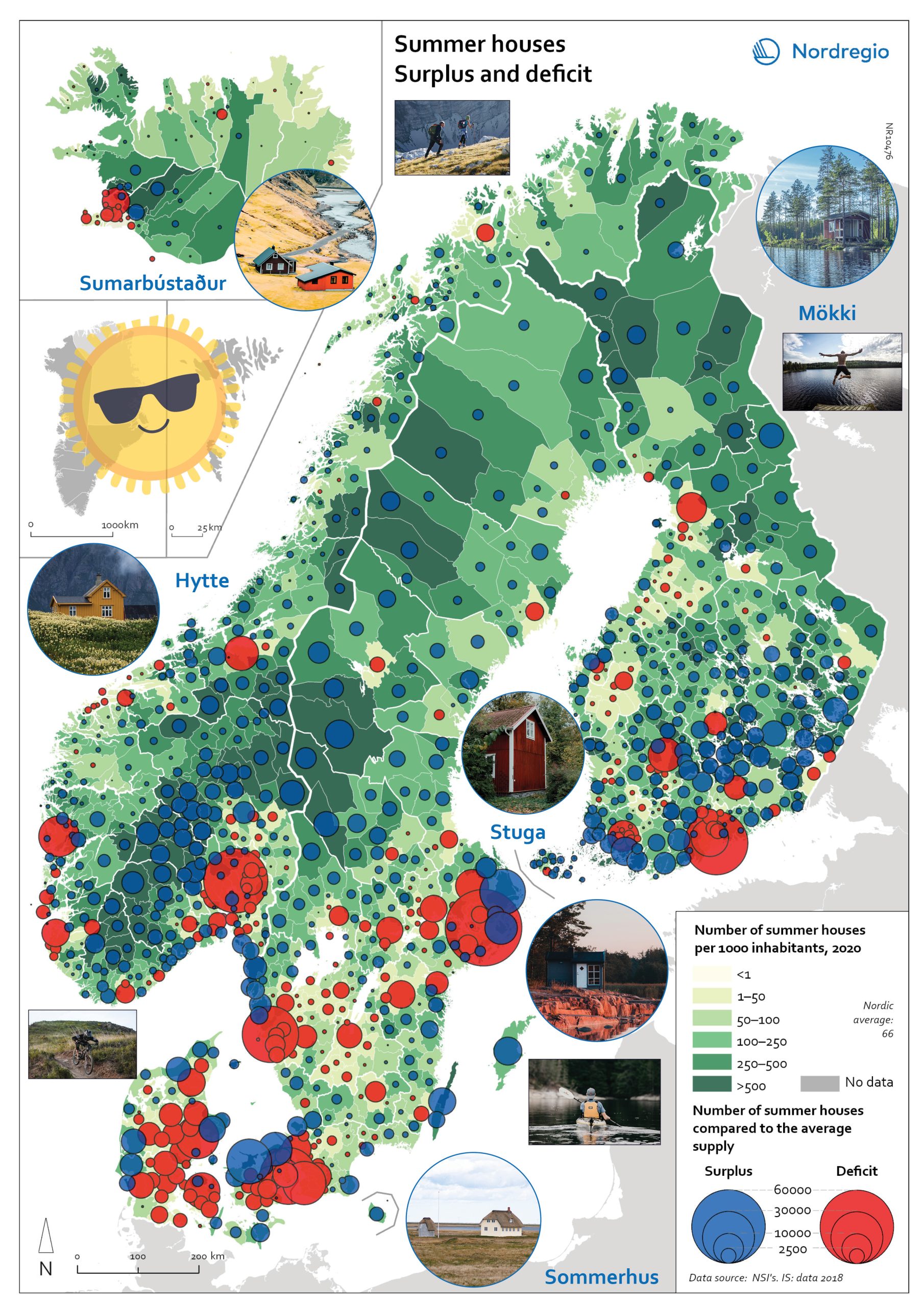

Gone missing: Nordic people!

Nordregio Summer Map 2022: Empty streets, closed restaurants – where is everyone? Nordic cities are about to quiet down as millions of people are logging out from work. But where do they go – Mallorca? Some yes, but the Nordic people are known for their nature-loving and private spirit, and most like to unwind in isolation. So, they head to their private paradises – to one of the 1.8 million summer houses around the Nordics, or as they would call them: sommerhus, stuga, hytte, sumarbústaður or mökki. The Nordregio Summer Map 2022 reveals the secret spots. The Finnish and Norwegians are most likely already packing their cars and leaving the cities: the highest supply of summer houses per inhabitant is found in Finland (92 summer houses per 1000 inhabitants) closely followed by Norway (82). The Swedish (59) Danish (40) and Icelandic (40) people seem to have more varied summer activities. There are large regional differences in the number of summer houses and the number of potential users – so not enough cabins where people would want them! And this is the dilemma Nordregio Summer Map 2022 shows in detail. Most people live in the larger urban areas while many summer houses are located in more remote and sparsely populated areas. The largest deficit of summer houses is found in Stockholm: with almost 1 million inhabitants, there is a need for 65,000 summer houses but the municipality has only 2,000 to offer! So, people living in Stockholm need to go elsewhere to find a summer house. The same goes for the other capital municipalities which have large deficits in summer houses: Oslo is missing 44,000, Helsinki 43,000, and Copenhagen 34,000. Fortunately, there are places that would happily accommodate these second-home searchers. Good news for Stockholm after all as the top-scoring municipality…

2022 June

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

Change in overnight stays for domestic visitors 2019–2020

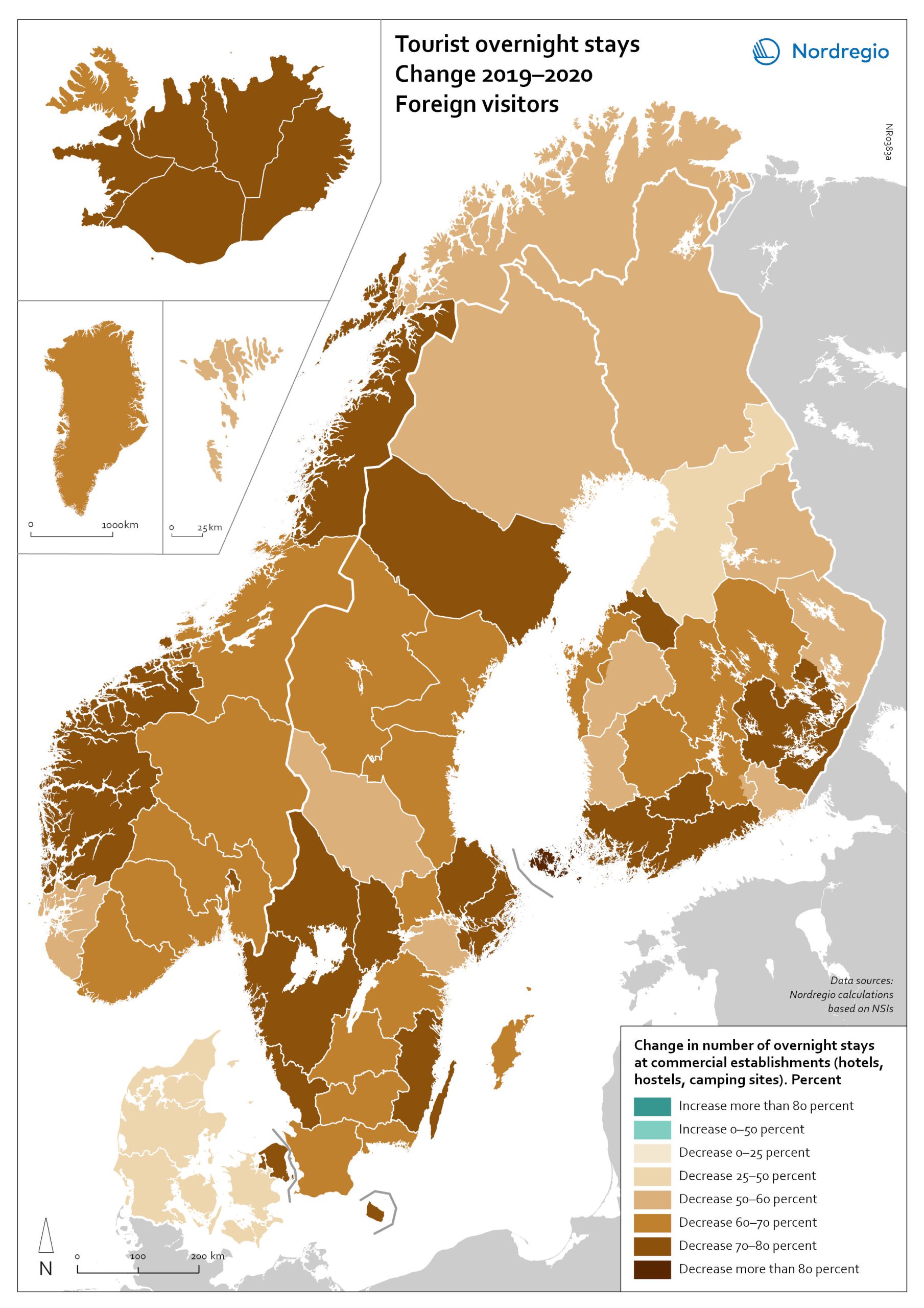

The map shows the relative change in the number of overnight stays at the regional level between 2019 and 2020 for domestic visitors. This map is related to the same map showing change in overnight stays for foreign visitors 2019–2020. The sharpest fall in visitors from abroad was in destinations where foreign tourists usually make up a high proportion of the total visitors. This is particularly relevant to islands like Åland (89% decrease on foreign visitors, from early 2019 to mid-2020) and to Iceland (66-77% drop depending on region). Lofoten and Nordland County in Norway, as well as Western Norway with Møre and Romsdal, which also have a high proportion of international tourists during the summer season due to their scenic landscape, also recorded sharp falls of 77-79% on foreign visitors during the same period. In Finland, the lake district (South Savo) and Southern Karelia, as well as the coastal Central Ostrobothnia (major cities Vasa and Karleby), recorded a 75-77% drop in the number of visitors from abroad. The fall here was mainly due to the lack of tourists from Russia. Even Finnish Lapland suffered a major fall in international visits during the winter peak period. For many local businesses that rely heavily on winter holidaymakers, the 2021/22 winter was a make-or-break season. In Sweden, the regions of Kalmar, Västra Götaland, Värmland and Örebro lost 77–79% of visitors from abroad, probably due to much fewer visitors from neighbouring Norway and from Denmark. In Denmark, the number of overnight stays by visitors from abroad to the Capital Region was down by 73%, whereas the number of domestic visitors declined by 27%. No region lost as many overnight visitors, both from abroad and domestic, as the capital cities and larger urban areas in the Nordic countries. Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki and Reykjavik…

2022 March

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

Change in overnight stays for foreign visitors 2019–2020

The map shows the relative change in the number of overnight stays at the regional level between 2019 and 2020 for foreign visitors. This map is related to the same map showing change in overnight stays for domestic visitors 2019–2020. The sharpest fall in visitors from abroad was in destinations where foreign tourists usually make up a high proportion of the total visitors. This is particularly relevant to islands like Åland (89% decrease on foreign visitors, from early 2019 to mid-2020) and to Iceland (66-77% drop depending on region). Lofoten and Nordland County in Norway, as well as Western Norway with Møre and Romsdal, which also have a high proportion of international tourists during the summer season due to their scenic landscape, also recorded sharp falls of 77-79% on foreign visitors during the same period. In Finland, the lake district (South Savo) and Southern Karelia, as well as the coastal Central Ostrobothnia (major cities Vasa and Karleby), recorded a 75-77% drop in the number of visitors from abroad. The fall here was mainly due to the lack of tourists from Russia. Even Finnish Lapland suffered a major fall in international visits during the winter peak period. For many local businesses that rely heavily on winter holidaymakers, the 2021/22 winter was a make-or-break season. In Sweden, the regions of Kalmar, Västra Götaland, Värmland and Örebro lost 77–79% of visitors from abroad, probably due to much fewer visitors from neighbouring Norway and from Denmark. In Denmark, the number of overnight stays by visitors from abroad to the Capital Region was down by 73%, whereas the number of domestic visitors declined by 27%. No region lost as many overnight visitors, both from abroad and domestic, as the capital cities and larger urban areas in the Nordic countries. Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki and Reykjavik…

2022 March

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

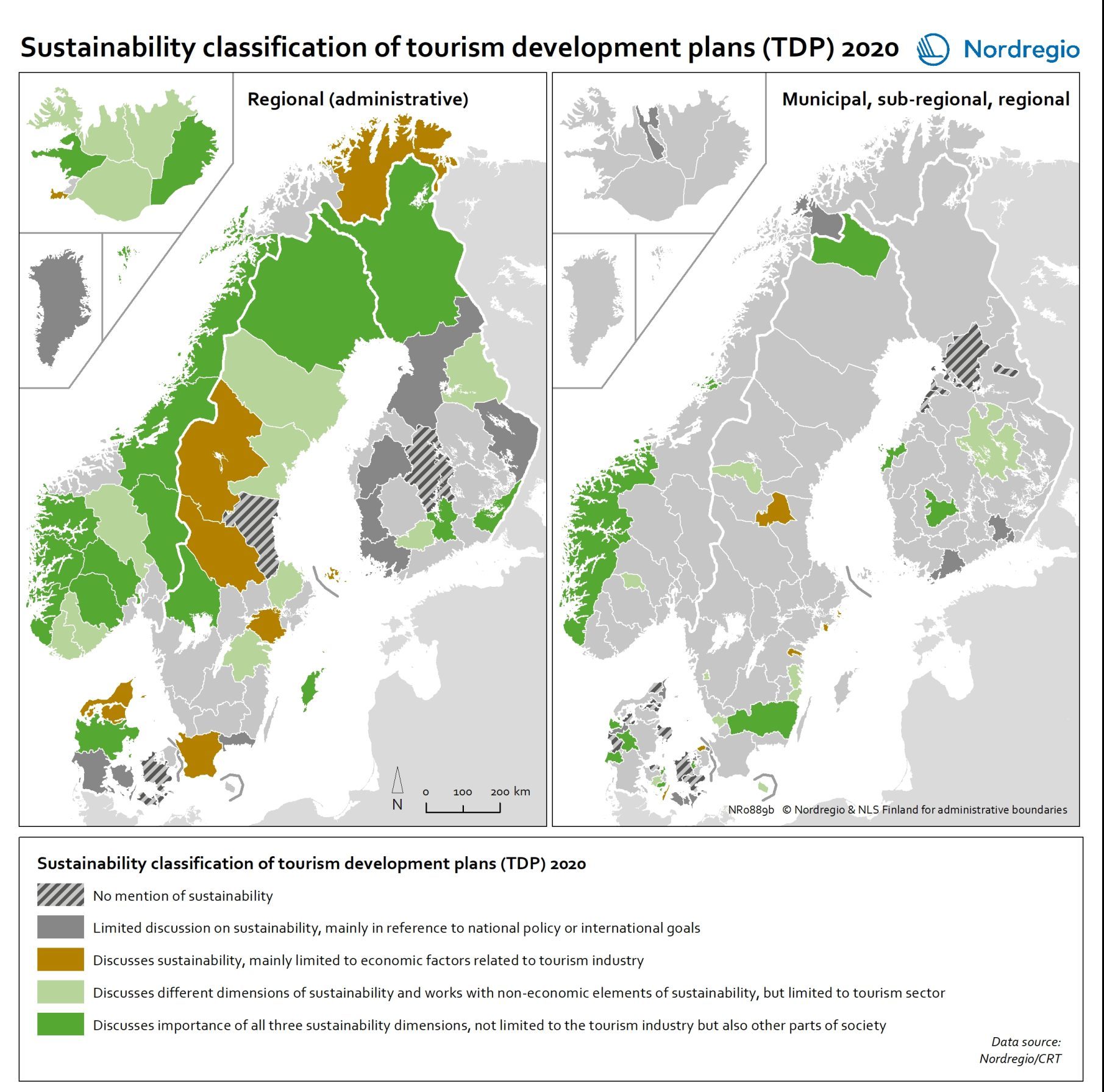

Sustainability classification of tourism development plans (TDPs)

This map indicates the distribution of different TDP sustainability concern treatment classes in the Nordic Region in 2020 Sustainability is seen as an important part of the tourism development in large parts of the Nordic rural regions, at least on paper. Some tourism policies even state it as the point of departure, the light that guides the way in everything that tourism involves. A growing public awareness of the need to transition to more sustainable practices, increased public pressure, along with political statements and commitments to do so, means that we should expect to find sustainability concerns and the SDGs strongly reflected in sub-national plans for tourism development, too. In this map, the dotted areas represent those TDPs that do not mention sustainability in any way. These mainly come from Denmark, as well as a few from Finland, Norway, and Sweden. The grey areas represent TDPs who mention the concept of sustainability, but in a very limited way, as a reference to an overall, global or international or national agenda, but without further operationalising or setting any goals regarding this for the local context. This type of treatment of sustainability concerns is mainly present in Finland, followed by Denmark and Sweden, plus a few cases from Norway and Iceland. Together, these two types represent almost two out of every five TDPs. They greyish green areas represent those TDPs which limit their discussion of sustainability to the economic sustainability of tourism businesses. This type of TDP is mainly found in Sweden, followed by Denmark, and then a case from each from Finland, Norway and Iceland. The green areas, which represent just under half of the TDPs, engage in a holistic treatment of sustainability concerns, including their economic, social and environmental aspects. The light green TDPs, with a tourism-centred sustainability treatment, come…

2021 December

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

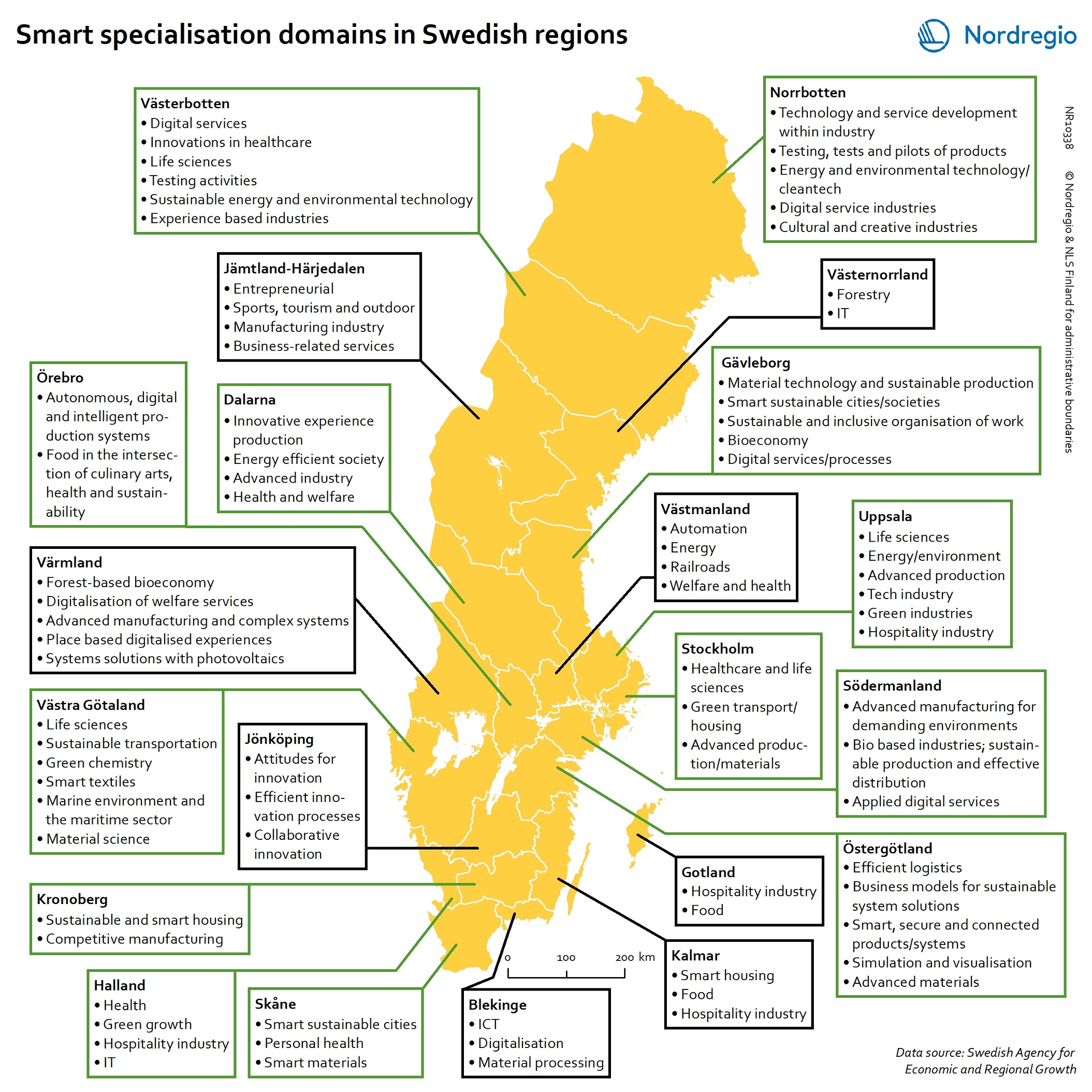

Smart specialisation domains in Swedish regions

This map gives an overview of the S3 focus areas in the Swedish regions in 2019. The major S3 domains in Sweden shown in the map provide a good overview of the key specialisation areas in Sweden. It is possible, for example, to check which Swedish regions have “green”, “sustainable”, “environment” at their smart specialisation domains (marked in green in their respective infoboxes for the domains in the figure). The information illustrated in the map can assist Swedish regions when they are considering opportunities for S3 synergy and co-operation with each other. In Sweden, the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (Tillväxtverket) is a central actor in assisting regions in their work with smart specialisation. Tillväxtverket promotes opportunities for cooperation between the Swedish regional S3 processes and provides relevant information and learning seminars related to S3. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Research and innovation

- Sweden

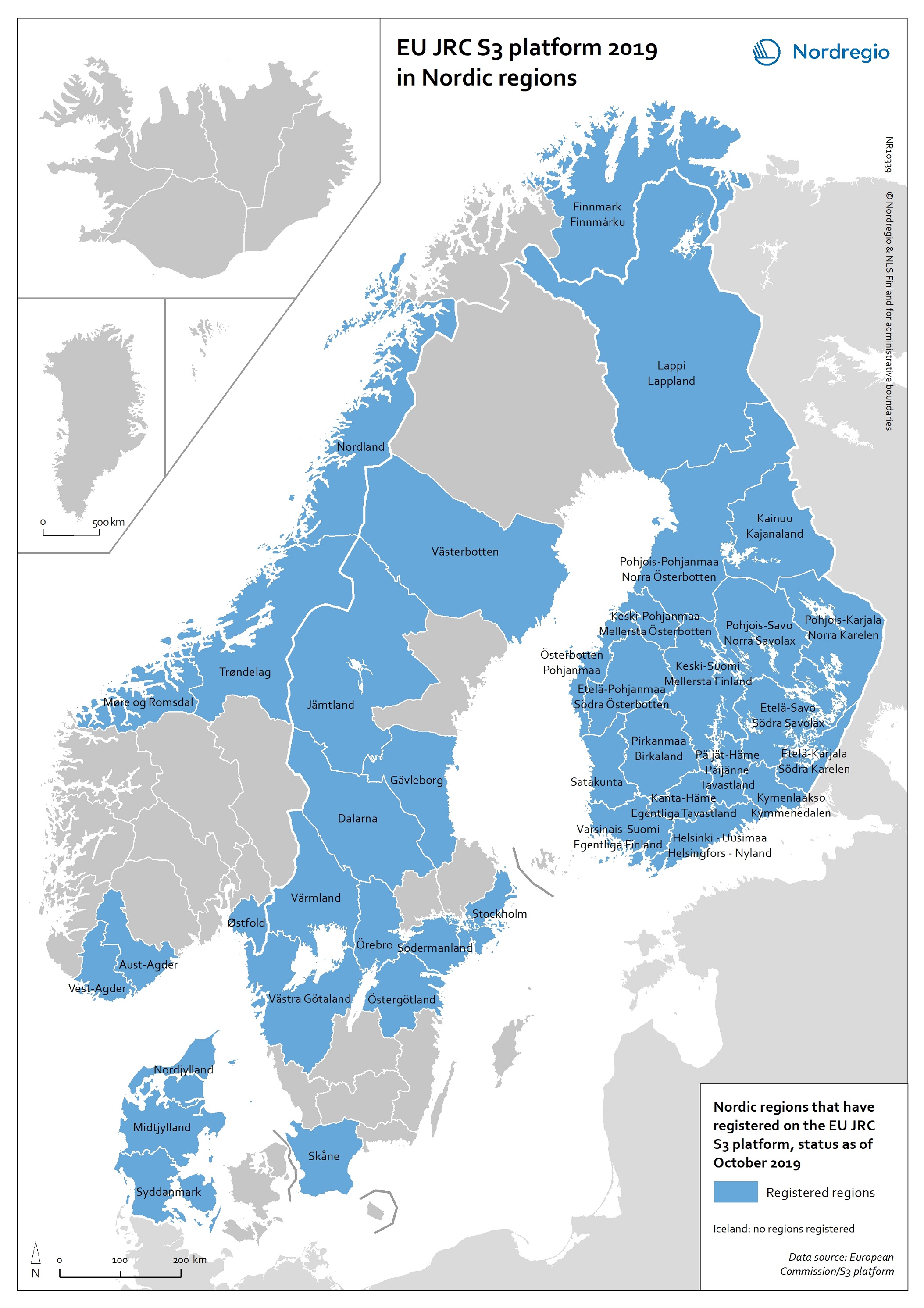

EU JRC S3 Platform 2019 in Nordic regions

This map shows the Nordic Regions that have registered on the EU JRC S3 platform, status as of October 2019. The regions that have registered on the S3 platform receive practical advice and broadened opportunities for international networking. In October 2019, there were 182 EU regions registered on the S3 platform, as well as 18 non-EU Member State regions. Of these regions, 38 are Nordic. It is worth noting that, as a non-EU member state, Norway has seven registered regions on the platform. Registration on the S3 platform is by no means a guarantee of success of a regional smart specialisation process, but it indicates the willingness of the region to learn more about S3 and to participate in international and interregional S3 cooperation through the possibilities provided by the S3 platform. The smart specialisation concept has been diffusing rapidly across Europe in the 2010s, as an increasing number of regions adopt it and design strategies departing from their own preconditions. The S3 platform in Seville, Spain, hosted by the Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS), was established in 2011 to assist EU countries and regions to develop, implement and review their smart specialisation strategies. The S3 platform provides information, methodologies, expertise and advice to national and regional policymakers, promotes mutual learning and transnational co-operation, and contributes to academic debates around the concept of smart specialisation. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

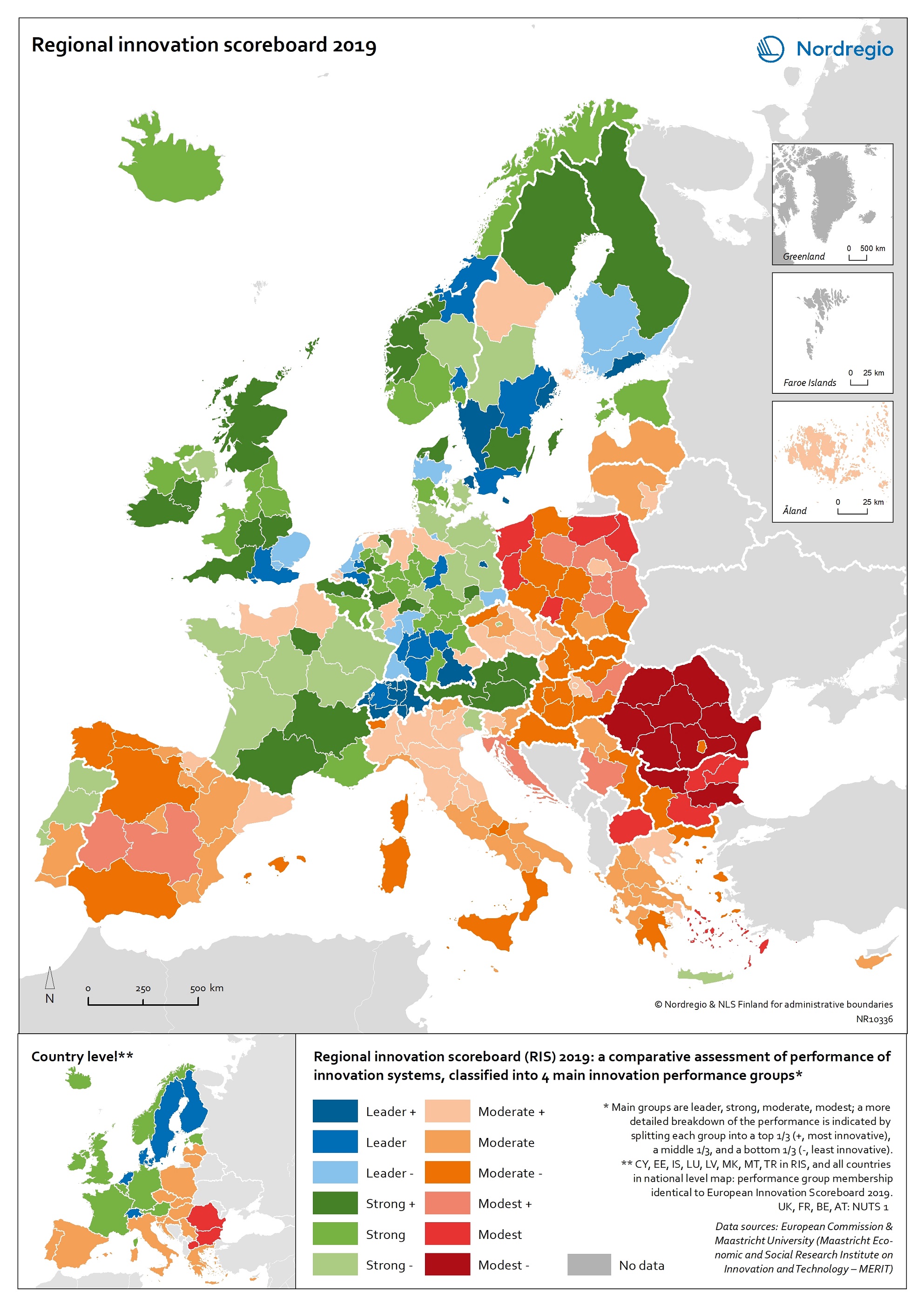

Regional innovation scoreboard 2019

This map shows the regional innovation scoreboard (RIS) in the European regions in 2019. The small map shows the innovation scoreboard at national level. The index shows the performance of innovation systems, classified into four main performance groups (leader, strong, moderate and modest). The European innovation scoreboard provides a comparative assessment of the research and innovation performance in European countries. It assesses the relative strengths and weaknesses of national innovation systems and helps countries identify areas they need to address. The Regional innovation scoreboard (RIS), a regional extension of the European innovation scoreboard, assesses the innovation performance of European regions on a limited number of indicators. The RIS 2019 covers 238 regions across 23 EU countries, as well as Norway, Serbia and Switzerland. Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Luxembourg and Malta are also included at country level. The RIS 2019 is a comparative assessment of regional innovation based on the European innovation scoreboard methodology, using 18 of the latter’s 27 indicators. It provides a more detailed breakdown of the performance groups with contextual data that can be used to analyse and compare structural economic, business and socio-demographic differences between regions. The Nordic regions are doing well in an overall RIS comparison regarding innovation performance. There are, however, considerable differences in innovation performance between the Nordic regions. For example, the capital regions have higher levels of innovation performance than more rural and peripheral regions, according to RIS 2019. This is often due to the critical mass of companies and the spatial significance of the proximity of firms and entrepreneurs, enabling knowledge-sharing and spill-over effects. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Europe

- Research and innovation

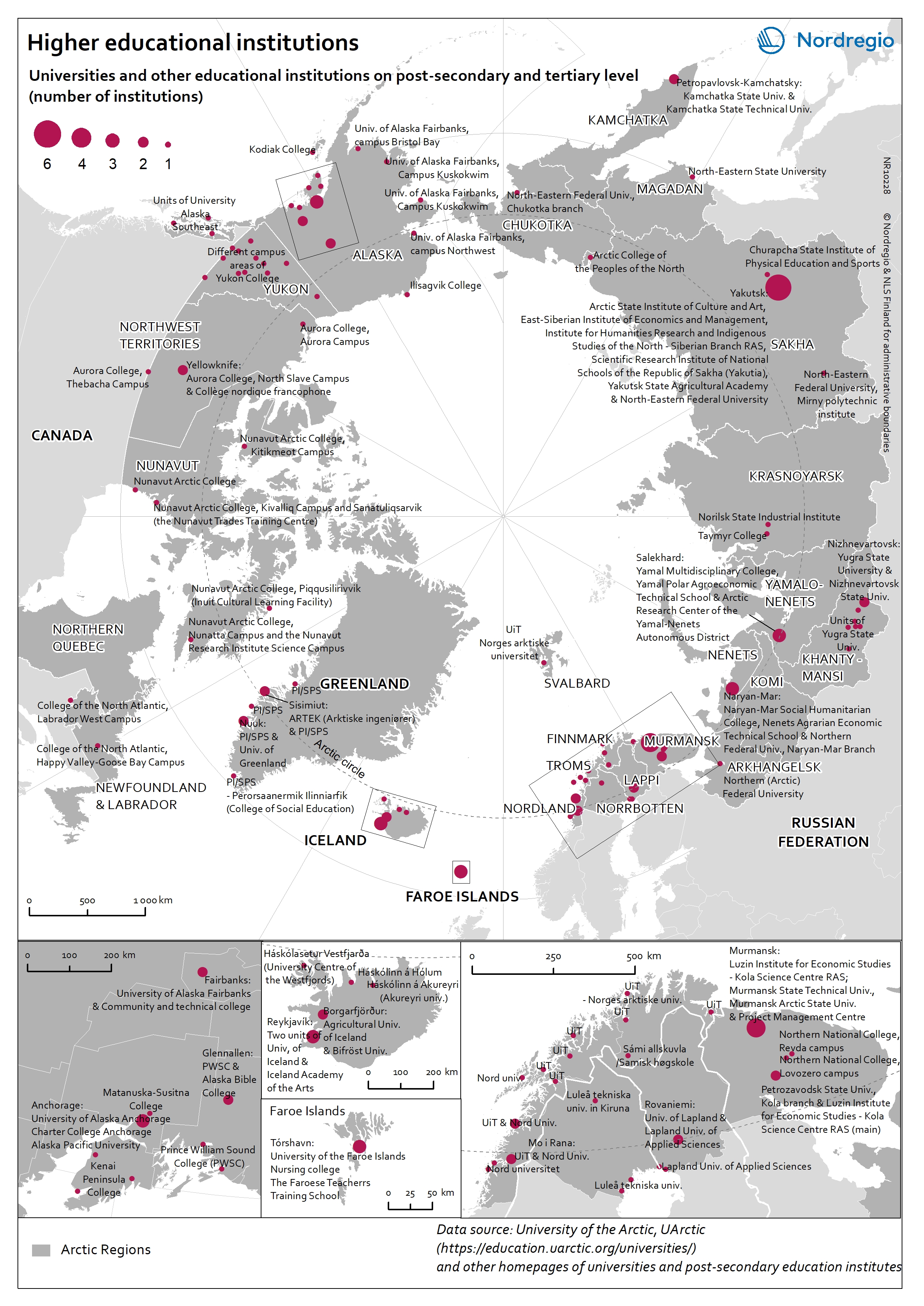

Higher educational institutions in the Arctic

The map shows universities and other educational institutions on post-secondary and tertiary level located in the Arctic. The red circles indicate a location of a university, college, or campus areas within the Arctic. The size of the circle corresponds to the number of educational institutions in a specific location. There is a high density of educational education institutions around Anchorage (Alaska), in Iceland, the Faroe Islands and the Arctic Fennoscandia (see zoom-in maps). In the Yukon (Canada), the Yukon College is the main educational institution, which has several campus areas across the region. In the Russian Arctic the largest centres with higher educational institutions are in Murmansk, Naryan-Mar (Nenets), Nizhnevartovsk (Khanty-Mansi), Salekhard (Yamalo-Nenets), and Yakutsk (Sakha).

2019 March

- Arctic

- Others

- Research and innovation

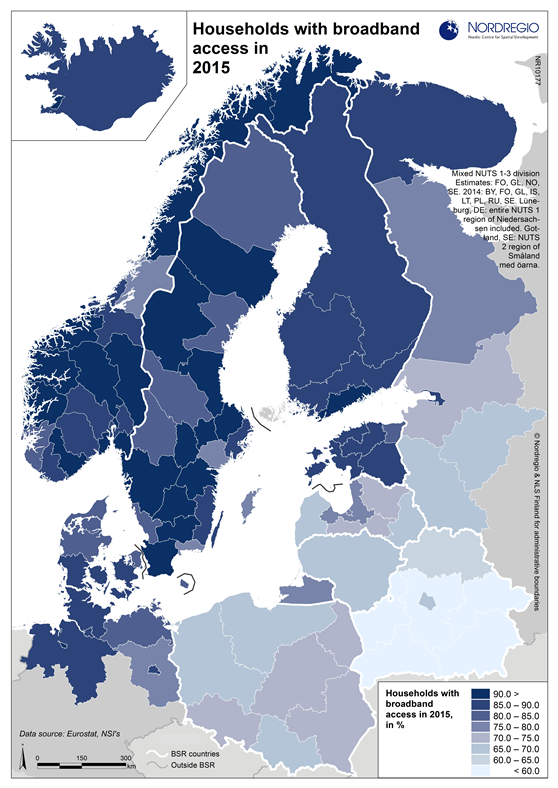

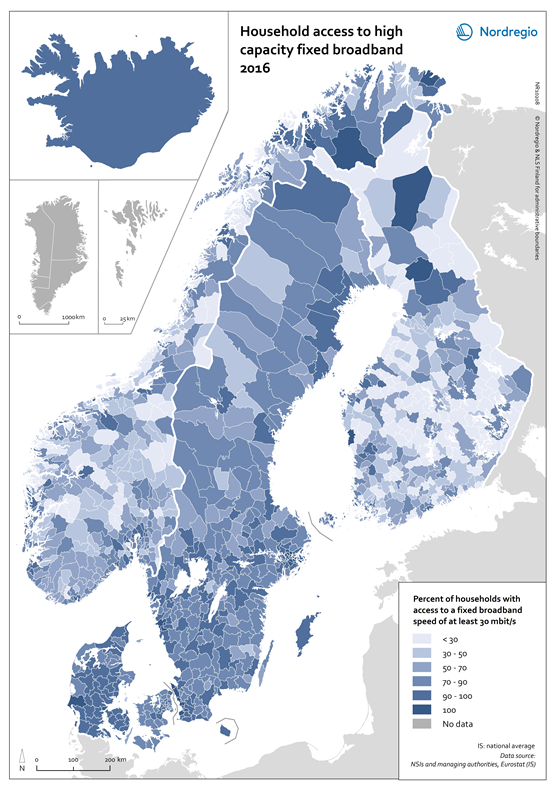

Household access to high capacity fixed broadband 2016

This map shows the household access to high capacity fixed broadband for all Nordic municipalities in 2016. The blue shading indicates the percentage of household with access to high capacity fixed broadband speed of at least 30 mbit/s in 2016. The darker the blue the larger the percentage of household with access to high capacity fixed broadband speed in the municipality, while the brightest colours represent municipalities with a low share. The grey colour indicate municipality with no data. High capacity fixed broadband coverage enhances access to digital solutions in both rural and urban contexts across the Nordic Region, thus making these areas good places to live, work and run a business domestically and across national borders. At a municipal level the household coverage by high capacity fixed broadband shows a more varied picture than that at the regional level. The average figure for Nordic municipalities was 63% in 2016, with more homogeneous figures in Denmark and Sweden than in Norway and Finland. The variation between neighbouring municipalities reflects the decision at the municipal level to prioritise investments in broadband infrastructure development as well as the nurturing of a favourable climate for the establishment of data centres requiring fast broadband networks, among other things. Fifteen Nordic municipalities, located in Sweden and Norway, had already reached the 100% mark for household coverage by high capacity fixed broadband in 2016. In Sweden, these municipalities are located in both the capital city region and in Skåne. In Norway, they are found in the more remote and rural parts of Møre og Romsdal (e.g. Giske), Troms (i.e. Lavangen) and Finnmark regions (Båtsfjord). Municipalities having values above 90% are mostly located in capital city regions as well as in more rural contexts in Jylland (Denmark), southern Sweden and northern Finland and Norway. One explanation for…

2018 February

- Nordic Region

- Others

- Research and innovation

Next Generation Access coverage 2016

This map shows the Next Generation Access (NGA) network coverage in European regions in 2016. The blue shading indicates the percentage of household covered by NGA broadband in European NUTS 3 regions. The darker the blue the larger the percentage of household covered by NGA broadband in the region, while the brightest colours represent regions with a low share. Regions with relatively small territories and important population densities stand out in terms of high NGA network coverage, e.g. urban regions in the Netherlands and Switzerland. Capital city regions also have high NGA network coverage scores, while the more rural regions continue to lag, e.g. in parts of France and Poland. The Nordic countries are characterised by having almost no differences within their territories, i.e. no large variation in terms of NGA network coverage, unlike the clear regional differences in countries such as France or Italy. All regions in the Nordic countries score in the range of 65% to 95% of households having NGA network coverage, except for Etelä-Pohjanmaa in Finland which has a coverage range of 35% to 65% and the Danish statistical region of Østjylland and the capital regions of Denmark and Iceland with scores between 95% and 100% respectively. The relatively high figures for the Nordic Region can in part be explained by the existence of national and regional digitalisation strategies over the last decade or so. In Denmark, as well as in the other Nordic countries, digitalisation has long been on the national agenda. One of the main goals of these strategies has been to increase the growth and productivity of the business community – and to make it easier and cheaper to establish digital infrastructure. The regional level has an important role to play in the development of digital infrastructure, hence the relevance of the elaboration…

2018 February

- Europe

- Others

- Research and innovation

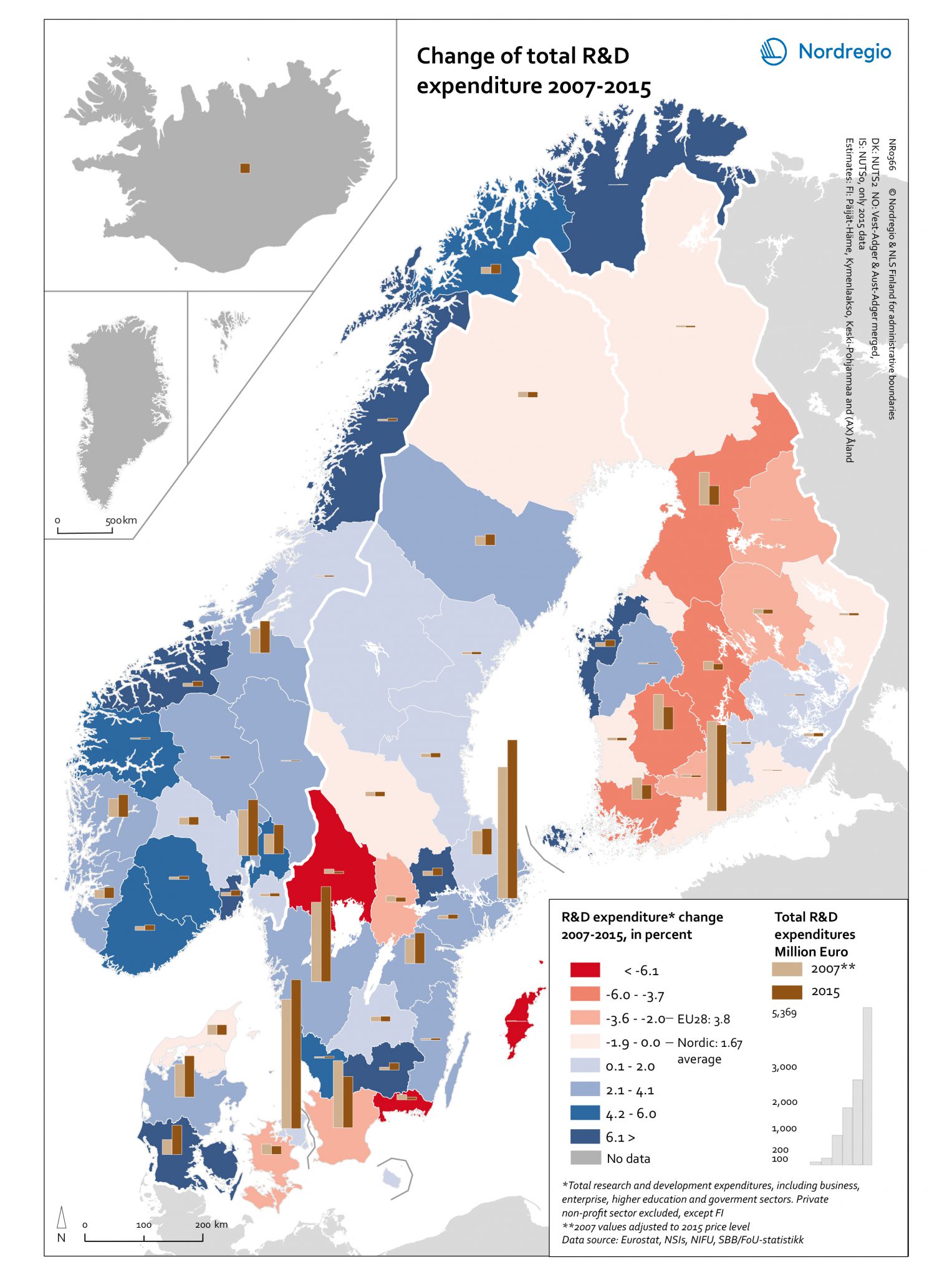

Change of total R&D expenditure 2007-2015

This map shows the change in the expenditure in research and development (R&D) between 2007 and 2015 in the Nordic Region. The blue tones indicate regions with a positive change in the R&D expenditure between 2007 and 2015. The red tones indicate regions with a negative change in the R&D expenditure between 2007 and 2015. The darker the colour, the stronger the change. The grey colour indicates no data. The bars indicate the value of expenditure in R&D in million euros, the light brown for 2007 and the dark brown for 2015. The values of 2007 expenditures were adjusted to 2015 price level. High levels of Research and Development (R&D) expenditure are viewed as a vital enabling factor for innovation which is one of the key policy components of the Europe 2020 Strategy. At the regional level in Finland, most regions have shown a downward trend in R&D expenditures both in percentage and in real terms. This reflects the challenging fiscal policy and economic conditions experienced in Finland after the global financial crisis in 2008 and the difficulties faced by the ICT sector, where R&D is highly concentrated, as well as the inability of other industries to compensate for the decline of the ICT sector. Åland on the other hand has shown a positive trend in R&D expenditures, although having very low values in absolute numbers for both years. Sweden has experienced a dramatic decrease (< -6.1%) in R&D expenditures in Värmland, Blekinge and Gotland which was in large part, if not entirely, caused by the relocation of important R&D facilities/resources. Similarly, some major closures and redundancy notifications led to substantial cuts in R&D spending in Skåne in 2015, despite the increasing number of start-ups. For Iceland, available data for the 2013–2016 period indicates a steady and stable increase in…

2018 February

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Research and innovation

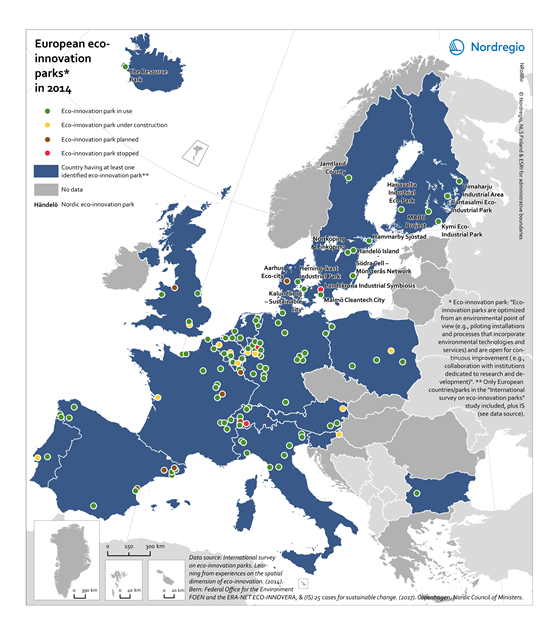

European eco-innovation parks in 2014

This map shows the location of the European eco-innovation parks in the states of the European Union (EU) and Iceland in 2014. The eco-innovation parks are eco-industrial parks and eco-innovative areas combining residential and industrial activities. The establishment of eco-industrial parks is one way to promote eco-innovation, resource efficiency and the circular economy. They create new and innovative business opportunities and improve ecosystems. The blue colour indicates the EU-member states having at least one identified eco-innovation park in 2014. The circles indicate the location and the type of the eco-innovation parks (green, in use; yellow, under construction; brown, planned; red, stopped). The grey colour indicates no data. A clear spatial concentration of eco-innovation parks can be observed in the Ruhr area and around Leipzig (Germany), in southern Belgium, south-western and northern Netherlands, western Switzerland, along the “arch” stretching from Turin via Pisa to Udine in North-East Italy, around Barcelona as well as around some national borders in the industrialised parts of north-West Europe namely Germany-Netherlands-Belgium-France and Switzerland. Eco-innovation parks differ in many respects, for instance regarding energy and material flows (e.g. waste heat, steam, power; wood chips, bark, ash, pulping chemicals), number and size of companies involved and jobs created, public sector involvement and finally, in terms of (the drivers behind) their evolution. The latter means that some parks evolved and expanded around a few economic activities and companies (e.g. saw mills) to include further activities (e.g. pulp mills, power plants etc.), while others were intentionally planned and put into operation.

2018 February

- Economy

- Europe

- Research and innovation