69 Maps

Gone missing: Nordic people!

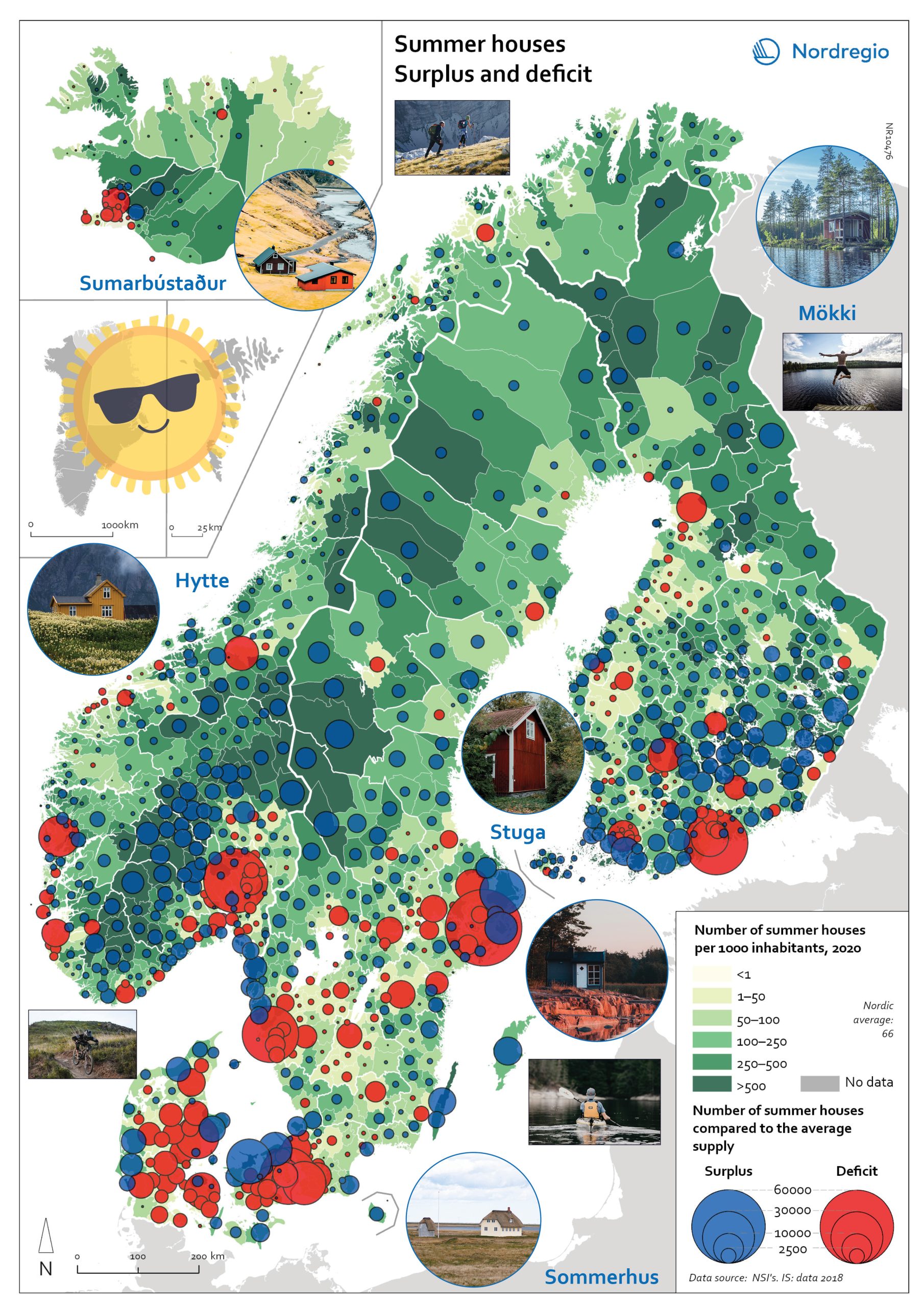

Nordregio Summer Map 2022: Empty streets, closed restaurants – where is everyone? Nordic cities are about to quiet down as millions of people are logging out from work. But where do they go – Mallorca? Some yes, but the Nordic people are known for their nature-loving and private spirit, and most like to unwind in isolation. So, they head to their private paradises – to one of the 1.8 million summer houses around the Nordics, or as they would call them: sommerhus, stuga, hytte, sumarbústaður or mökki. The Nordregio Summer Map 2022 reveals the secret spots. The Finnish and Norwegians are most likely already packing their cars and leaving the cities: the highest supply of summer houses per inhabitant is found in Finland (92 summer houses per 1000 inhabitants) closely followed by Norway (82). The Swedish (59) Danish (40) and Icelandic (40) people seem to have more varied summer activities. There are large regional differences in the number of summer houses and the number of potential users – so not enough cabins where people would want them! And this is the dilemma Nordregio Summer Map 2022 shows in detail. Most people live in the larger urban areas while many summer houses are located in more remote and sparsely populated areas. The largest deficit of summer houses is found in Stockholm: with almost 1 million inhabitants, there is a need for 65,000 summer houses but the municipality has only 2,000 to offer! So, people living in Stockholm need to go elsewhere to find a summer house. The same goes for the other capital municipalities which have large deficits in summer houses: Oslo is missing 44,000, Helsinki 43,000, and Copenhagen 34,000. Fortunately, there are places that would happily accommodate these second-home searchers. Good news for Stockholm after all as the top-scoring municipality…

2022 June

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

Change in overnight stays for domestic visitors 2019–2020

The map shows the relative change in the number of overnight stays at the regional level between 2019 and 2020 for domestic visitors. This map is related to the same map showing change in overnight stays for foreign visitors 2019–2020. The sharpest fall in visitors from abroad was in destinations where foreign tourists usually make up a high proportion of the total visitors. This is particularly relevant to islands like Åland (89% decrease on foreign visitors, from early 2019 to mid-2020) and to Iceland (66-77% drop depending on region). Lofoten and Nordland County in Norway, as well as Western Norway with Møre and Romsdal, which also have a high proportion of international tourists during the summer season due to their scenic landscape, also recorded sharp falls of 77-79% on foreign visitors during the same period. In Finland, the lake district (South Savo) and Southern Karelia, as well as the coastal Central Ostrobothnia (major cities Vasa and Karleby), recorded a 75-77% drop in the number of visitors from abroad. The fall here was mainly due to the lack of tourists from Russia. Even Finnish Lapland suffered a major fall in international visits during the winter peak period. For many local businesses that rely heavily on winter holidaymakers, the 2021/22 winter was a make-or-break season. In Sweden, the regions of Kalmar, Västra Götaland, Värmland and Örebro lost 77–79% of visitors from abroad, probably due to much fewer visitors from neighbouring Norway and from Denmark. In Denmark, the number of overnight stays by visitors from abroad to the Capital Region was down by 73%, whereas the number of domestic visitors declined by 27%. No region lost as many overnight visitors, both from abroad and domestic, as the capital cities and larger urban areas in the Nordic countries. Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki and Reykjavik…

2022 March

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

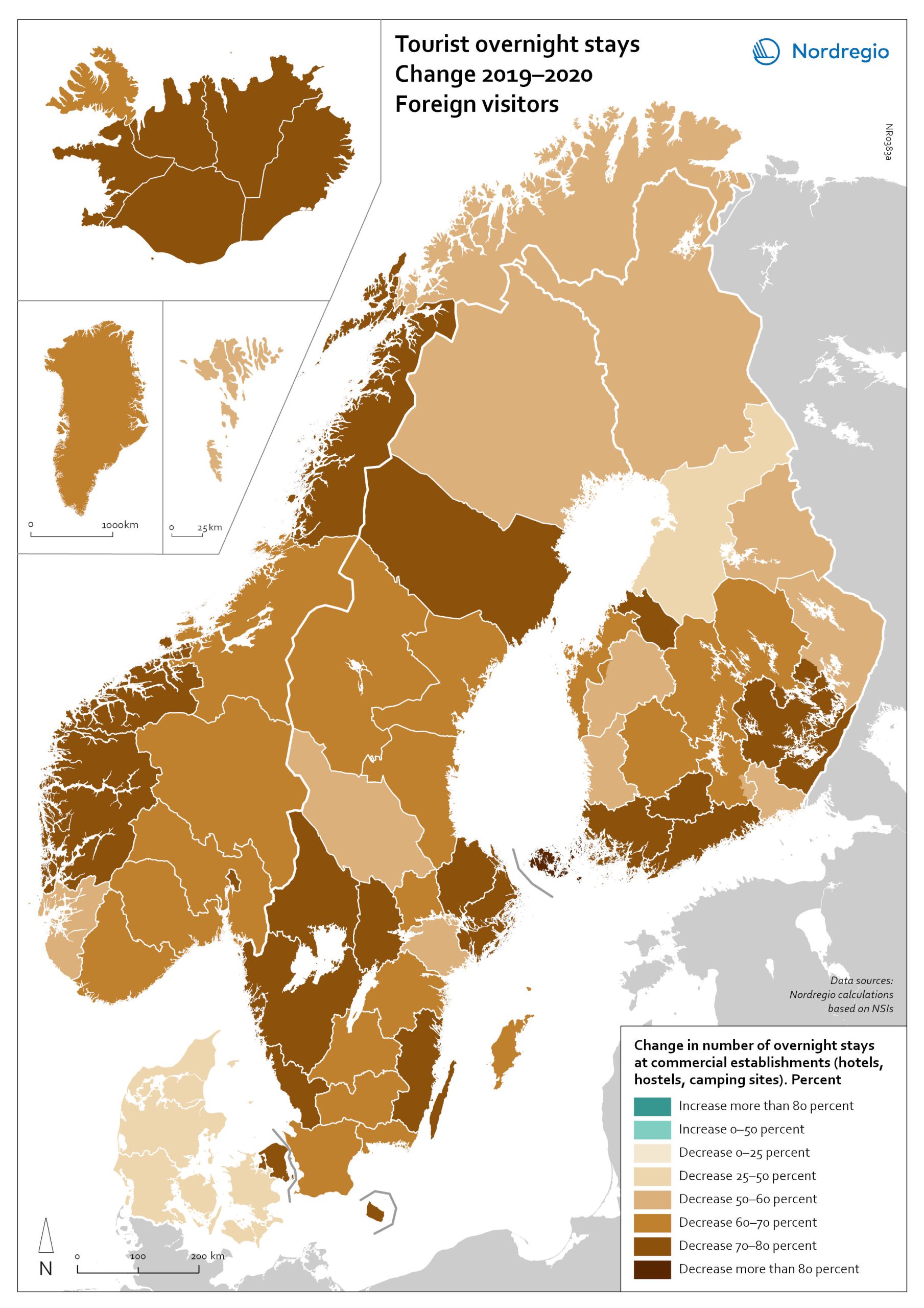

Change in overnight stays for foreign visitors 2019–2020

The map shows the relative change in the number of overnight stays at the regional level between 2019 and 2020 for foreign visitors. This map is related to the same map showing change in overnight stays for domestic visitors 2019–2020. The sharpest fall in visitors from abroad was in destinations where foreign tourists usually make up a high proportion of the total visitors. This is particularly relevant to islands like Åland (89% decrease on foreign visitors, from early 2019 to mid-2020) and to Iceland (66-77% drop depending on region). Lofoten and Nordland County in Norway, as well as Western Norway with Møre and Romsdal, which also have a high proportion of international tourists during the summer season due to their scenic landscape, also recorded sharp falls of 77-79% on foreign visitors during the same period. In Finland, the lake district (South Savo) and Southern Karelia, as well as the coastal Central Ostrobothnia (major cities Vasa and Karleby), recorded a 75-77% drop in the number of visitors from abroad. The fall here was mainly due to the lack of tourists from Russia. Even Finnish Lapland suffered a major fall in international visits during the winter peak period. For many local businesses that rely heavily on winter holidaymakers, the 2021/22 winter was a make-or-break season. In Sweden, the regions of Kalmar, Västra Götaland, Värmland and Örebro lost 77–79% of visitors from abroad, probably due to much fewer visitors from neighbouring Norway and from Denmark. In Denmark, the number of overnight stays by visitors from abroad to the Capital Region was down by 73%, whereas the number of domestic visitors declined by 27%. No region lost as many overnight visitors, both from abroad and domestic, as the capital cities and larger urban areas in the Nordic countries. Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki and Reykjavik…

2022 March

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

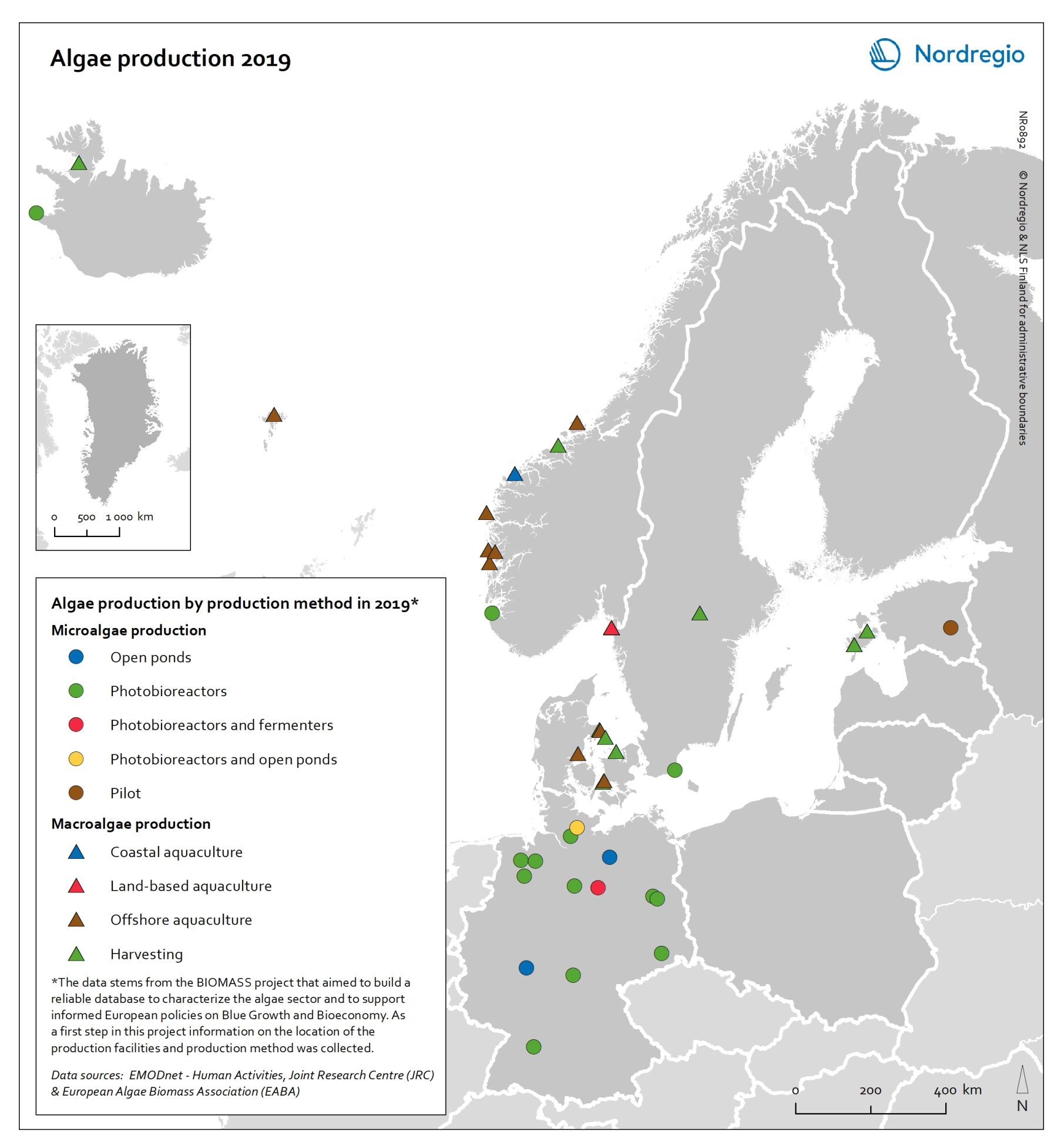

Algae production in 2019

This map shows location of algae production by production method in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region in 2019 Algae and seaweeds are gaining attention as useful inputs for industries as diverse as energy and human food production. Aquatic vegetation – both in the seas and in freshwater – can grow at several times the pace of terrestrial plants, and the high natural oil content of some algae makes them ideal for producing a variety of products, from cosmetic oils to biofuels. At the same time, algae farming has added value in potential synergies with farming on land, as algae farms utilise nutrient run-off and reduce eutrophication. In addition, aquatic vegetation is a highly versatile feedstock. Algae and seaweed thrive in challenging and varied conditions and can be transformed into products ranging from fuel, feeds, fertiliser, and chemicals, to third-generation sugar and biomass. These benefits are the basis for seaweed and algae emerging as one of the most important bioeconomy trends in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea region. The production of algae for food and industrial uses has hence significant potential, particularly in terms of environmental impact, but it is still at an early stage. The production of algae (both micro- and macroalgae) can take numerous forms, as shown by this map. At least nine different production methods were identified in the region covered in this analysis. A total of 41 production sites were operating in Denmark, Estonia, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway, Germany, and Sweden. Germany has by far the most sites for microalgae production, whereas Denmark and Norway have the most macroalgae sites.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Others

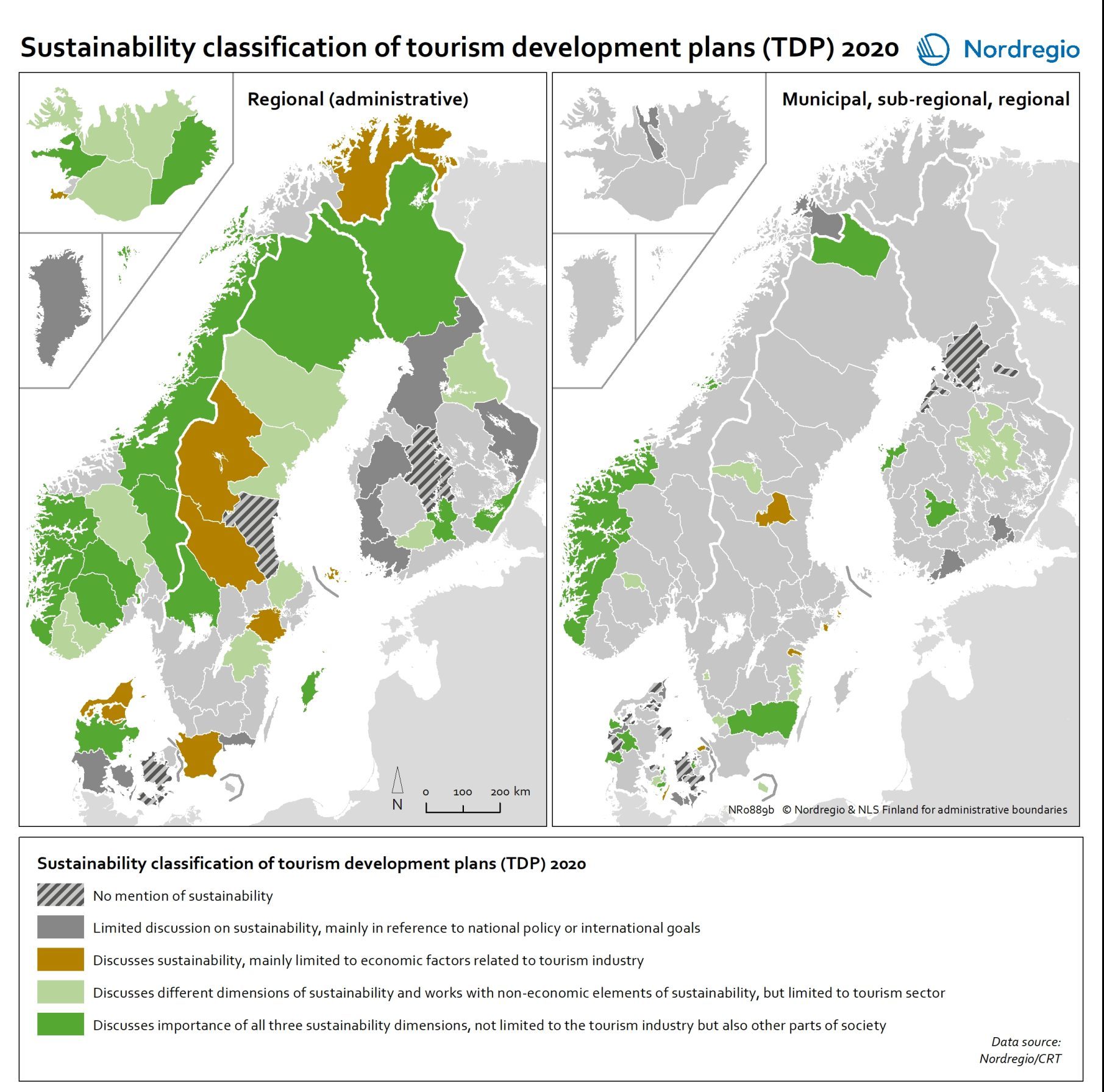

Sustainability classification of tourism development plans (TDPs)

This map indicates the distribution of different TDP sustainability concern treatment classes in the Nordic Region in 2020 Sustainability is seen as an important part of the tourism development in large parts of the Nordic rural regions, at least on paper. Some tourism policies even state it as the point of departure, the light that guides the way in everything that tourism involves. A growing public awareness of the need to transition to more sustainable practices, increased public pressure, along with political statements and commitments to do so, means that we should expect to find sustainability concerns and the SDGs strongly reflected in sub-national plans for tourism development, too. In this map, the dotted areas represent those TDPs that do not mention sustainability in any way. These mainly come from Denmark, as well as a few from Finland, Norway, and Sweden. The grey areas represent TDPs who mention the concept of sustainability, but in a very limited way, as a reference to an overall, global or international or national agenda, but without further operationalising or setting any goals regarding this for the local context. This type of treatment of sustainability concerns is mainly present in Finland, followed by Denmark and Sweden, plus a few cases from Norway and Iceland. Together, these two types represent almost two out of every five TDPs. They greyish green areas represent those TDPs which limit their discussion of sustainability to the economic sustainability of tourism businesses. This type of TDP is mainly found in Sweden, followed by Denmark, and then a case from each from Finland, Norway and Iceland. The green areas, which represent just under half of the TDPs, engage in a holistic treatment of sustainability concerns, including their economic, social and environmental aspects. The light green TDPs, with a tourism-centred sustainability treatment, come…

2021 December

- Nordic Region

- Tourism

Change in share of biofuels in transport from 2010 to 2018

This map shows change in share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region from 2010 to 2018. Even though a target for greater use of biofuels has been EU policy since the Renewable Energy and Fuel Quality Directives of 2009, development has been slow. The darker shades of blue on the map represent higher increase, and the lighter shades of blue reflect lower increase. The lilac color represent decrease. The Baltic Sea represents a divide in the region, with countries to the north and west experiencing growth in the use of biofuels for transport in recent years. Sweden stands out (16 per cent growth), while the other Nordic countries has experienced more modest increase. In the southern and eastern parts of the region, the use of biofuels for transport has largely stagnated. Total biofuel consumption for transport has risen more than the figure indicates due to an increase in transport use over the period.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

Share of biofuels in transport in 2018

This map shows the share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region in 2018. There has been considerable political support for biofuels and in the EU, this debate has been driven by the aim of reducing dependency on imported fuels. For instance, 10 per cent of transport fuel should be produced from renewable sources. The darker shades on the map represent higher proportions, and the lighter shades reflect lower proportions. As presented by the map, only Sweden (20.7%) had reached the 10 per cent target in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Region in 2018. Both Finland (8.3%) and Norway (8.3%) were close by the target, while the other countries in the region were still lagging behind, particularly the Baltic countries.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

Higher educational institutions in the Arctic

The map shows universities and other educational institutions on post-secondary and tertiary level located in the Arctic. The red circles indicate a location of a university, college, or campus areas within the Arctic. The size of the circle corresponds to the number of educational institutions in a specific location. There is a high density of educational education institutions around Anchorage (Alaska), in Iceland, the Faroe Islands and the Arctic Fennoscandia (see zoom-in maps). In the Yukon (Canada), the Yukon College is the main educational institution, which has several campus areas across the region. In the Russian Arctic the largest centres with higher educational institutions are in Murmansk, Naryan-Mar (Nenets), Nizhnevartovsk (Khanty-Mansi), Salekhard (Yamalo-Nenets), and Yakutsk (Sakha).

2019 March

- Arctic

- Others

- Research and innovation

Natural population change in the Arctic

The map shows the annual natural population change rates in the Arctic subregions between 2013 and 2017. The blue tones indicate a positive change: subregions where the number of live births exceeds the number of deaths. The yellow colour indicates no or little change: subregions where the difference between births and deaths are close to zero. The red tones indicate negative change: subregions where the number of deaths exceed the number of live births. In the Artic the annual average natural population change rate was 0,66% between 2013 and 2017. The natural population change was positive especially in the Canadian Arctic, Alaska (USA), Greenland as well as in Yamalo-Nenets, Khanty-Mansi and in Sakha regions (Russian Federation). Natural population decline was the strongest in the Nordic Arctic, as well as in Murmansk, Magadan, and Kamchatka (Russian Federation).

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

Tertiary educational attainment level in the Arctic

The map shows the percent of individuals aged 25-64 with tertiary education as the highest attainment level in the Arctic regions in 2017. Tertiary education corresponds to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011 levels 5-8, which represent bachelor or equivalent and all higher attainment levels. The dark green tones show regions where more than 30% of individuals attained tertiary education as highest level. The light green tones show regions where less than 15% of individuals attained tertiary education as highest level. Highest shares of working aged population with tertiary education were found in Troms (Norway, 43,8%) and Iceland (42,5%). All other Nordic Arctic regions as well as Yukon (Canada, 33,3%) and in some regions in Alaska (USA) had high shares of highly educated people. Northern Quebec (Canada) had the lowest share of working aged population that attained tertiary education (13,0%).

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

- Economy

Upper secondary educational attainment level in the Arctic

The map shows the percent of individuals aged 25-64 with upper secondary education as highest level attained in 2017 in Arctic regions. The upper secondary education corresponds to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011 levels 3-4. The dark blue tones show regions where more than 80% of individuals attained upper secondary education as highest level. The lightest blue tones show regions where less than 60% of individuals attained upper secondary education as highest level. Among the working age population, the number of individuals with upper secondary education was the highest in Alaska (USA, over 90%). Individuals with upper secondary education attainment level was also high – above 80% – in the Yukon and Labrador (Canada), Norrbotten (Sweden), and in Lappi (Finland). The lowest share of individual with upper secondary education was in Greenland (45,6%), Chukotka (Russian Federation, 58,4%) and in Nunavut (Canada, 59,1%).

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

Labour force participation rate in the Arctic

The map shows the regional labour force (active population) as share of total population in the Arctic regions in 2016. The active population includes all persons (aged 15 years old and over) with at least one current paid job or searching for one. The dark green tones show regions with high participation rates and correspondingly light green tones show regions with low participation rates. The Russian Arctic regions of Chukotka (83,6%), Yamalo-Nenets (78,0%), and Magadan (76,1%) had the highest participation rates. The lowest participation rates were in Lappi (Finland, 53,3%) and in Nordland (Norway, 59,9%).

2019 March

- Arctic

- Economy

- Labour force

Unemployment rate in the Arctic

The map shows unemployed persons as share of the labour force (aged 15 years old and over) in the Arctic regions in 2016. The dark orange tones show regions with high unemployment rates and correspondingly light orange tones show regions with low unemployment rate. Nunavut and Newfoundland and Labrador (Canada, 14,0% and 13,4%, respectively) had the highest unemployment rates. The unemployment rate was the lowest in Finnmark, Nordland, and Troms (Norway, 2,6%, 3,3%, and 3,3%, respectively), in the Faroe Islands (3,3%), in Iceland (3,0%), as well as in three Russian Arctic regions: Magadan (3,1%), Yamalo-Nenets (3,1%), and Chukotka (3,2%). The unemployment rate in the Arctic regions mostly follows the national averages.

2019 March

- Arctic

- Economy

- Labour force

Part-time employment incidence in the Arctic

The map shows the share of the part-time employees over total employment in the Arctic regions in 2014. Part-time workers are considered as persons (aged 15 years old and over) who are working less than 30 hours per week. The dark blue tones show regions with high part-time employment incidence and correspondingly light blue tones show regions with low part-time employment incidence. The three Arctic regions of Norway had the highest part-time employment incidence: Nordland (59,5%), Troms (56,3%), and Finnmark (56,0%). The Russian Arctic regions of Yamalo-Nenets (0,9%), Khanty-Mansi (2,5%), and Chukotka (3,4%) had the lowest part-time employment incidence.

2019 March

- Arctic

- Economy

- Labour force

Employment rate in the Arctic

The map shows the employment rate for the Arctic regions in 2016 based on OECD data. The employment rate is the ratio between the employed population and the working age population (aged 15 years old and over). Employed persons are aged 15 or over who report that they have worked in gainful employment for at least one hour in the previous week or who had a job but were absent from work during the reference week. The dark blue tones show regions with high employment rates and correspondingly light blue tones show regions with low employment rate. The highest employment rates in the Arctic regions were in the Faroe Islands, Svalbard, the Yukon (Canada), Chukotka, Yamalo-Nenets, and Magadan Oblast (Russian Federation). The lowest employment rates were in Finnish Lapland (48,1%), Newfoundland & Labrador, and Nunavut (Canada, 52,4% and 53,0%, respectively). The employment rate in the Nordic Arctic regions was lower than the average of their respective countries whereas in Alaska (USA) and the Russian Arctic the employment rate was higher than average of their respective countries.

2019 March

- Arctic

- Economy

- Labour force

Population change in Arctic settlements

The map provides an overview of the population change in Arctic settlements with 500 inhabitants or more during the period 2000 to 2017. The purple underlaying layer shows the extent of permafrost across the Arctic. The circles indicate settlements with 500 inhabitants or more and are proportional to the total population in 2017. Blue tones indicate population growth between 2000 and 2017, while red tones indicate population decline. Four zoomed-in maps show areas with high settlement density – Arctic Fennoscandia, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Alaska. In Alaska, population increased in the largest settlements between 2000 and 2017. The population decline in small settlements located far from the two large cities – Anchorage and Fairbanks – has been caused by outmigration, which has cancelled out the positive natural population growth. In the Canadian Arctic, most people live in a few settlements. Similar to Alaska, the population increased in the largest settlements and decreased in small settlements. Most of the smaller settlements in Arctic Fennoscandia have witnessed a population decline between 2000 and 2017, except in Norway. The dominant pattern in Fennoscandia is a population growth in larger settlements and a population decline in surrounding smaller settlements. This is similar to the pattern observed in the other Nordic Arctic countries – Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands. New inhabitants settled in the capitals (Reykjavik, Nuuk, and Torshavn) and regional centres, from both domestic and international locations, while settlements in sparsely populated areas are becoming less attractive to incomers. In the Russian Arctic, the regions can be divided into the oil and gas areas of the Khanty-Mansi and Yamal-Nenets, and other areas. The population is growing in the oil and gas areas and declining slowly in the others. Over 75% of the settlements have been shrinking throughout the 21st century, mainly because…

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

- Migration

Share of youth population in the Arctic

The map shows the population aged 15-24 as share of the total population in 2017 at the regional level in the Arctic. Age 15 to 24 is a standard international definition of youth used by the OECD and United Nations. Dark blue tones indicate regions with high share of youth in the total population, and light blue tones indicate regions with low share of youth. Keewatin in Nunavut region (Canada) had the highest share of youth (18,8%). Region 3 in the Northwest Territories, Northern Quebec, as well as the other two regions in Nunavut (Canada) had a share of youth above 15%. Magadan (9,2%), Arkhangelsk (9,4%) and Komi (9,7%) (Russian Federation) had the lowest shares of youth in their total populations.

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

Share of working age population in the Arctic

The map shows the population aged 15-64 as a share of the total population in 2017 at the sub-regional level in the Arctic. Dark purple tones indicate subregions with high share of working age population, and light purple tones indicate subregions with low share of working age population. In the Arctic the share of the working age population was 69,8%. The highest share of working age population was in regions where a large share of employment is related to natural resources extraction such as oil, gas, and minerals. This is especially the case in the Russian Arctic regions. All subregions in the Nordic countries had a share of working age population smaller than 60%. Subregions in the Russian Federation as well as in Svalbard (Norway) and in Aleutian Islands (Alaska) had high shares of working age population.

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

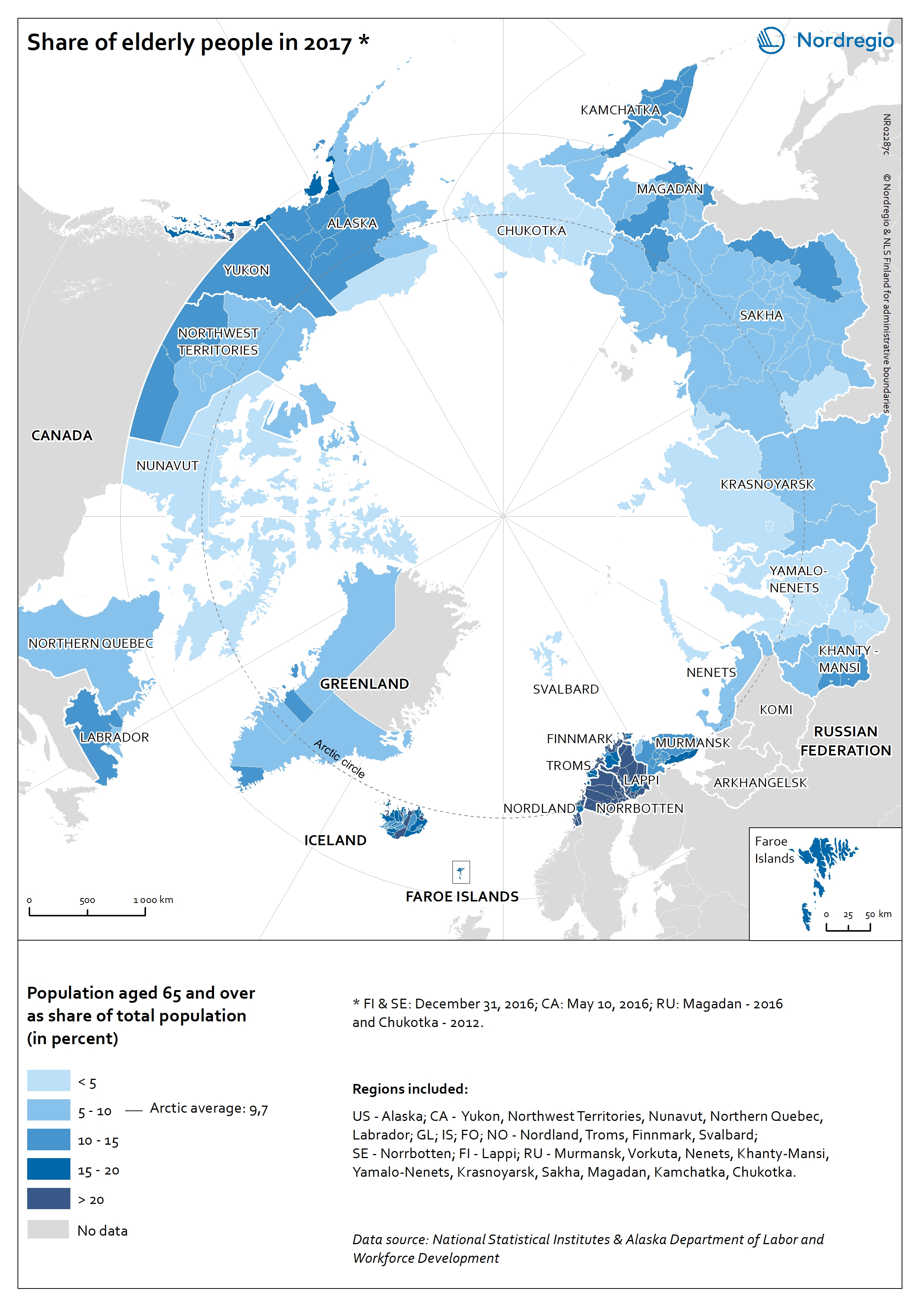

Share of elderly population in the Arctic

The map shows the population aged 65 and over as share of the total population in 2017 at the sub-regional level in the Arctic. Dark blue tones indicate subregions with high share of elderly people, light blue tones show subregions low share of elderly population. The Arctic is generally characterized by a low share of elderly (9,7%), especially in the subregions of Yamalo-Nenets, Krasnoyarsk, and Chukotka (Russian Federation), and Nunavut (Canada). Many of the Nordic subregions had a share of elderly over 20%, as well as in the Haines Borough (Alaska).

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

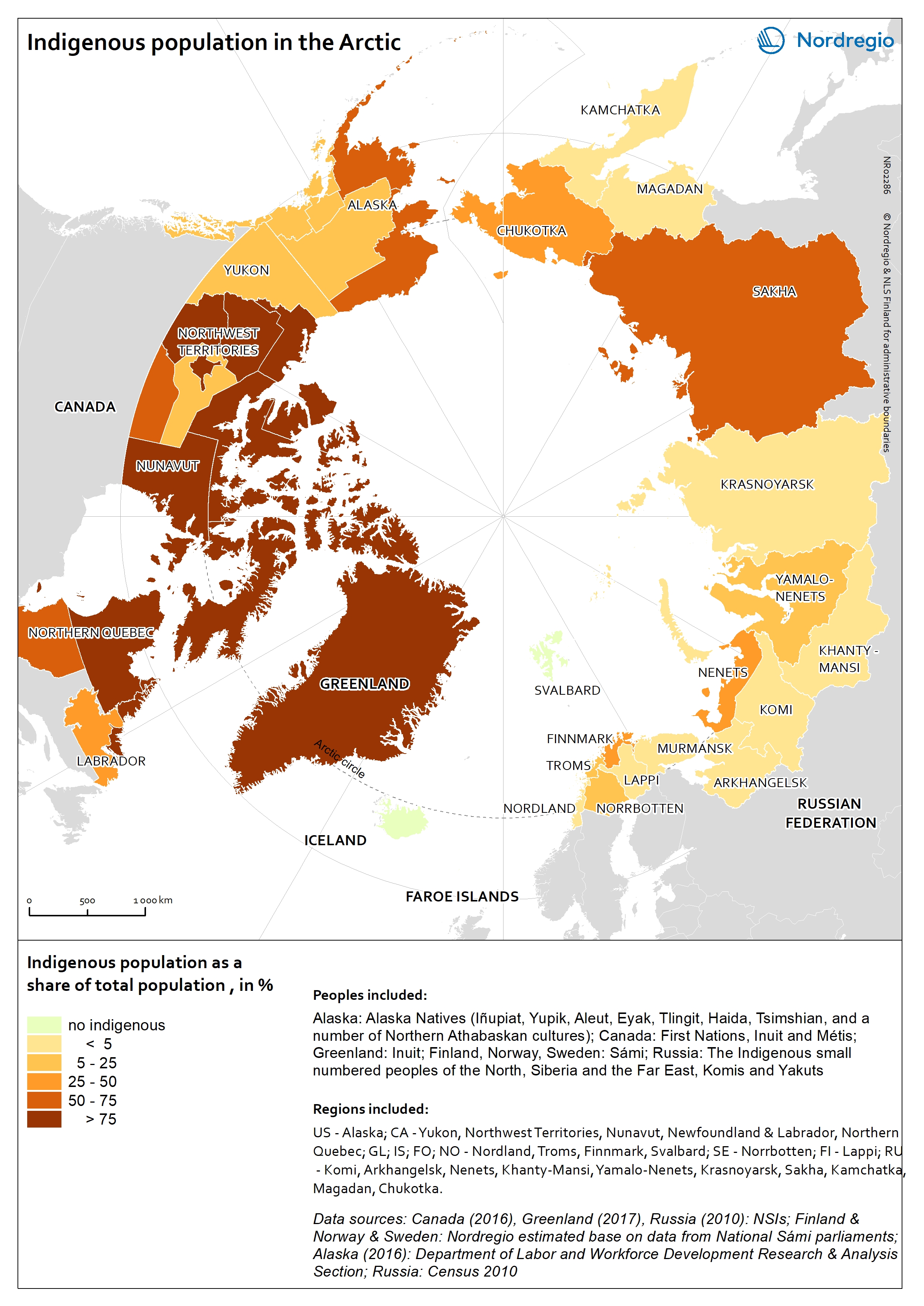

Indigenous population in the Arctic

The map shows the indigenous population as a share of the total population in the Arctic. Approximately one million people, or 9% of the total population in the Arctic is indigenous. Indigenous population reassembles more than 40 different ethnic groups. In terms of statistics there are no circumpolar definition of an indigenous person and therefore the number of indigenous people is based on different national definitions. Official statistics do not necessarily recognize indigenous populations separately. The indigenous population is the highest in the Canadian Arctic and in Greenland, weighing more than 75% of the total population. The Yukon, the southern part of Northern Quebec, and Labrador and Newfoundland (Canada) have the lowest shares of indigenous population. In the remaining part of the Arctic, indigenous peoples represent less than half of the total population, except in Sakha (Russian Federation), Southwest Region and Northern Region (Alaska, USA) where 50-75% of the population is indigenous. There are no indigenous people in Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Svalbard.

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography