69 Maps

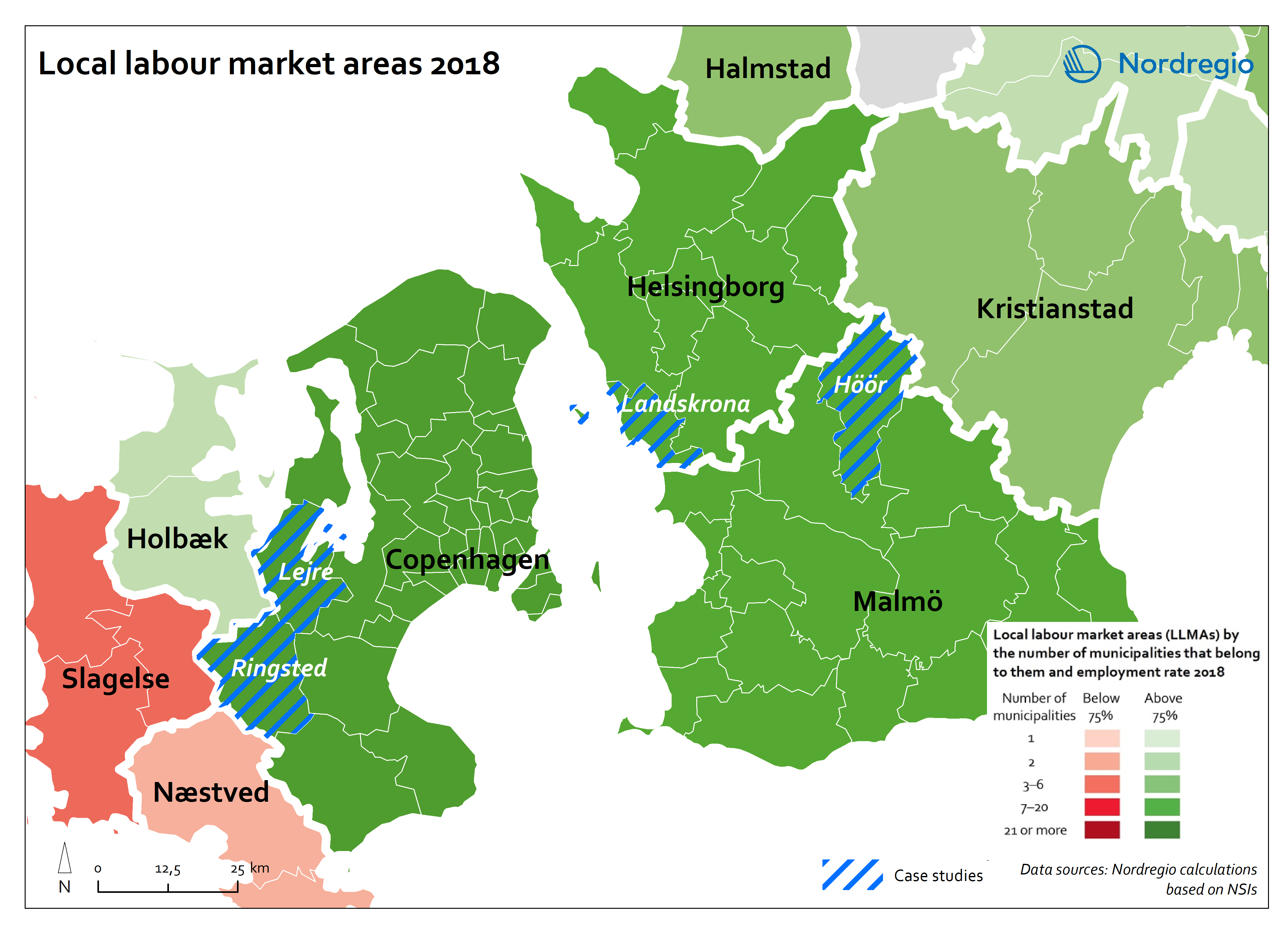

Access to fixed broadband at minimum download speed 100 Mpbs

The map shows the proportion of households that had access to fixed-line broadband with download speeds >100 Mbps (superfast broadband) at the municipal level, with darker colours indicating higher coverage. Overall, Denmark has the highest levels of connectivity, with 92% of municipalities providing superfast broadband to at least 85% of households. In over half (59%) of all Danish municipalities, almost all (>95%) of households have access to this connection speed. The lowest levels of connectivity are found in Finland. This is particularly evident in rural municipalities where, on average, less than half of households (48%) have access to superfast broadband. Connectivity levels are also rather low in some parts of Iceland, for example, the Westfjords and several municipalities in the east. Households in urban municipalities are still more likely to have access to superfast broadband than households in rural or intermediate municipalities, but the gap appears to be closing in most. This is most evident in Norway, where the average household coverage for rural municipalities increased by 31% between 2018 and 2020. By comparison, average household coverage for urban municipalities in Norway increased by only 0.7%. In the archipelago (Åland Islands, Stockholm and Helsinki), general broadband connectivity is good; however, some islands with many second homes still have poor coverage.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Others

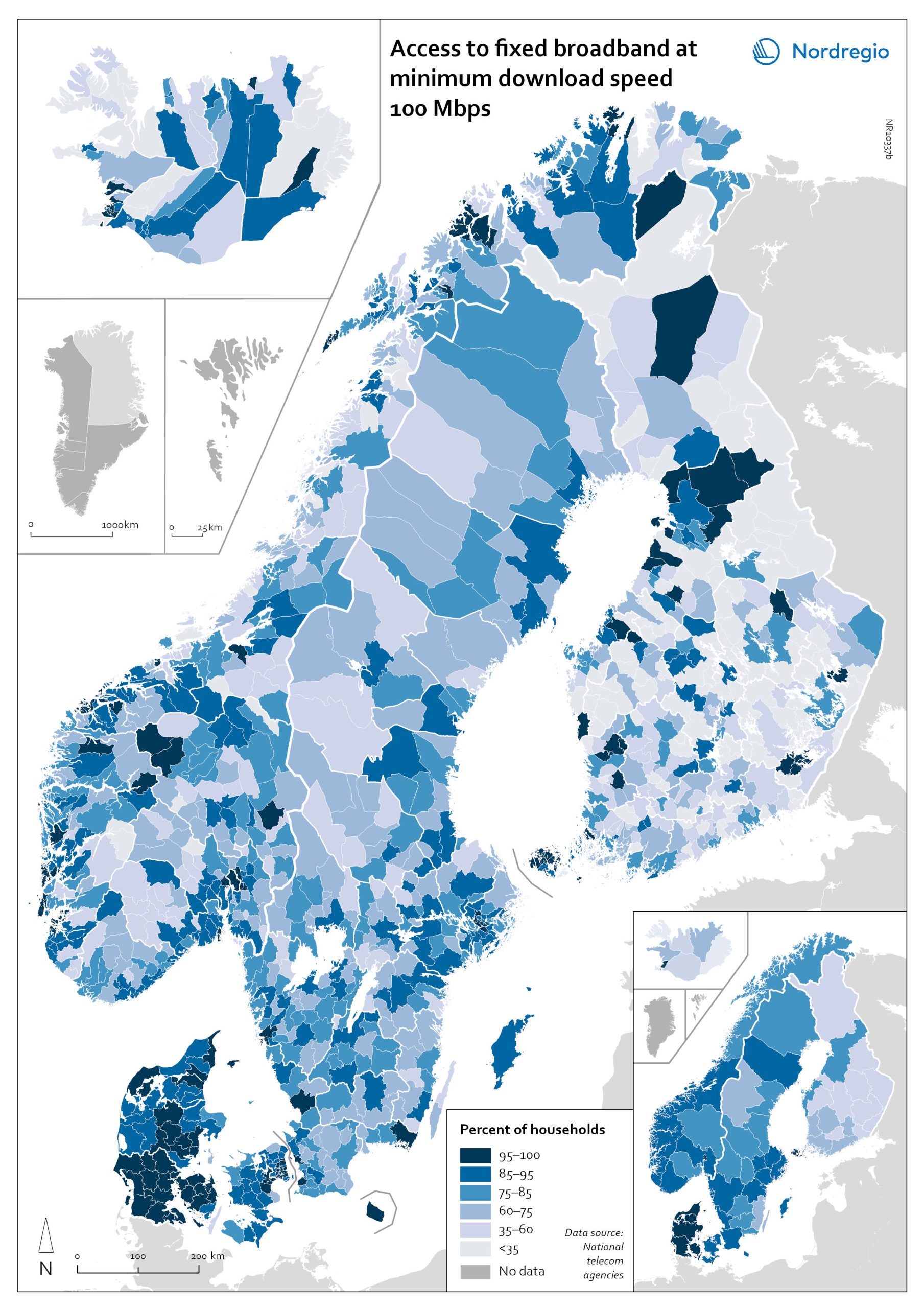

Change in work travels Jan-Feb 2020 compared to Nov 2021

The map shows changes in number of people travelling to work in the Nordic municipalities with the biggest populations comparing November 2021 to a pre-pandemic baseline. The map compares the average number of people who travelled to work on a weekday in January and February 2020 with the number of people who travelled to work on 11 November 2021 in the ten largest cities of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. The date was selected as the reference date as it is considered to be a relatively typical Thursday. It also represents a point when few movement restrictions were in place in the Nordic countries. As can be seen from the map, all of the municipalities highlighted recorded a fall in work-related travel on 11 November compared to the pre-pandemic baseline. It was biggest in Stavanger (-36%), followed by Stockholm (-31%), Oulu (-30%), Bærum (adjacent to Oslo) (-29%), Frederiksberg (adjacent to Copenhagen) (-29%) and Helsinki (-29%). In general, the decrease was highest around the capital regions and larger cities, but there were exceptions, for example, Jyväskylä (-26%), Örebro (-25%), Jönköping (-21%), and Randers (-20%). Several large municipalities also stood out because their patterns did not change so much, for example, Helsingborg (-3%) and Västerås (-7%) in Sweden; Viborg (-3%) and Odense (-8%) in Denmark.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

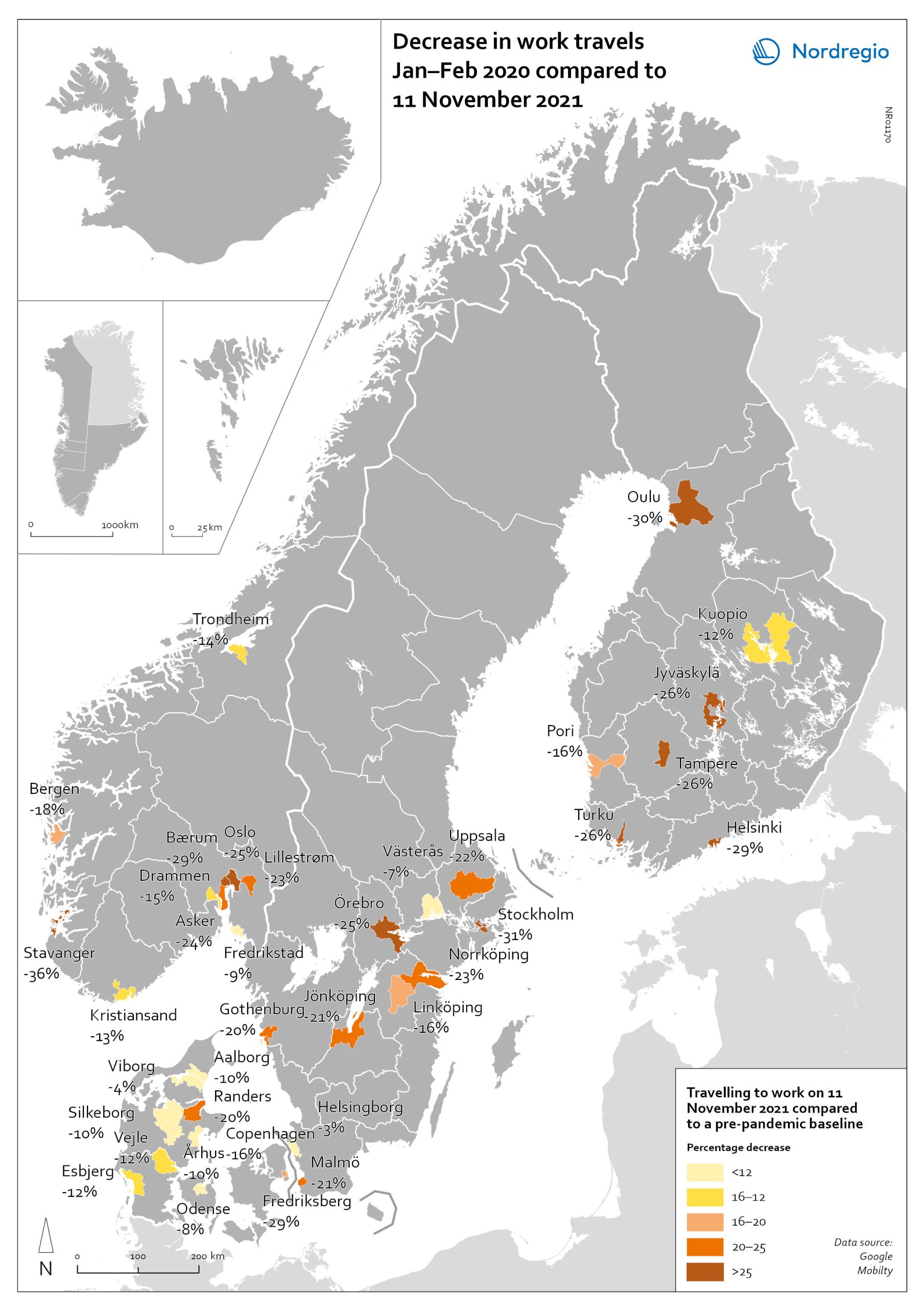

Remote work potential

The map shows the share of jobs that can potentially be done from home. At the municipal level it shows that the highest proportion is in, or in the proximity of, the largest urban conurbations. The purple areas show the municipalities that has a remote-work potential above the Nordic average (37%) and the blue areas the municipalities with remote-work potential below the Nordic average. The indicator is based on the methodology of Dingel & Neiman (2020). This method estimates the proportion of jobs that can theoretically be performed from home based on the tasks included in different occupations. Dingel & Neiman’s US classification was translated to the European International Standard Classification of Operations (ISCO-08) codes. The data is based on the 4-digit ISCO-08 and includes 437 occupations. The result was that every 4-digit ISCO occupation was coded as either 1: possible to work from home or not possible to work from home. For more information about the method please look at the State of the Nordic Region 2022 publication. The ten municipalities with the highest proportions are all in capital regions, with seven out of 10 in either Copenhagen (Hovedstaden) or Stockholm Region. In general, people in urban municipalities are more likely to be able to work from home (46.2%) than those in intermediate municipalities (32.3%) and rural municipalities (27.8%). It seems to be the case that the higher proportion of jobs that can be done from home in urban areas relates to the differences in industrial and occupational profiles between urban and rural areas, in particular, a higher concentration of knowledge-intensive occupations in urban areas. These differences are also evident when comparing countries. For example, Denmark has a rather large number of municipalities with high proportions of jobs that can be done from home. This may be due to…

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

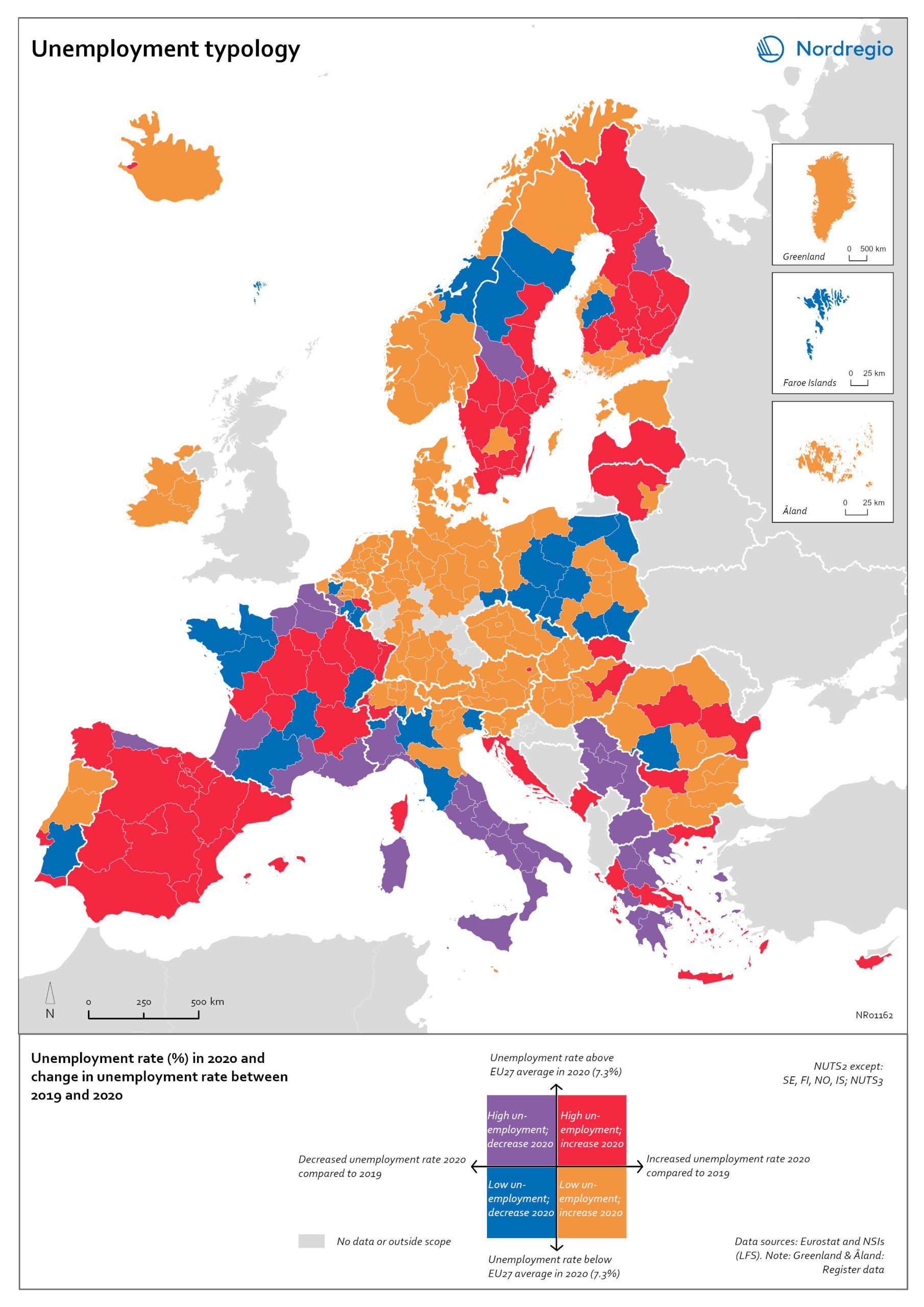

Unemployment typology

The map shows a typology of European regions by combining information on pre-pandemic unemployment rates with unemployment rates in 2020, based on the annual Labour Force Survey (LFS) that is measured in November. On one axis, the typology considers the extent of the change in the unemployment rate between 2019 and 2020. On the other axis, it considers whether the unemployment rate in 2020 was above or below the EU average of 7.3%. Regions are divided into four types based on whether the unemployment rate decreased or increased and how it relates to the EU average. Regions falling into the first type, shown in red on the map, had an increase in the unemployment rate in 2020 as well as an above-average unemployment rate in general in 2020. These regions were most affected by the pandemic. They are mainly found in northern and central parts of Finland, southern and eastern Sweden, the capital area of Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Spain and central parts of France. Regions falling into the second type, shown in orange on the map, had an increase in the unemployment rate in 2020 but a below-average unemployment rate in general in 2020. These regions had low pre-pandemic unemployment rates and so were not as badly affected as the red regions, despite the rising unemployment rates. They are located in Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Åland, southern and western Finland, Sweden (Gotland, Jönköping, and Norrbotten), Estonia, Ireland, northern Portugal and central and eastern parts of Europe.

2022 March

- Europe

- Labour force

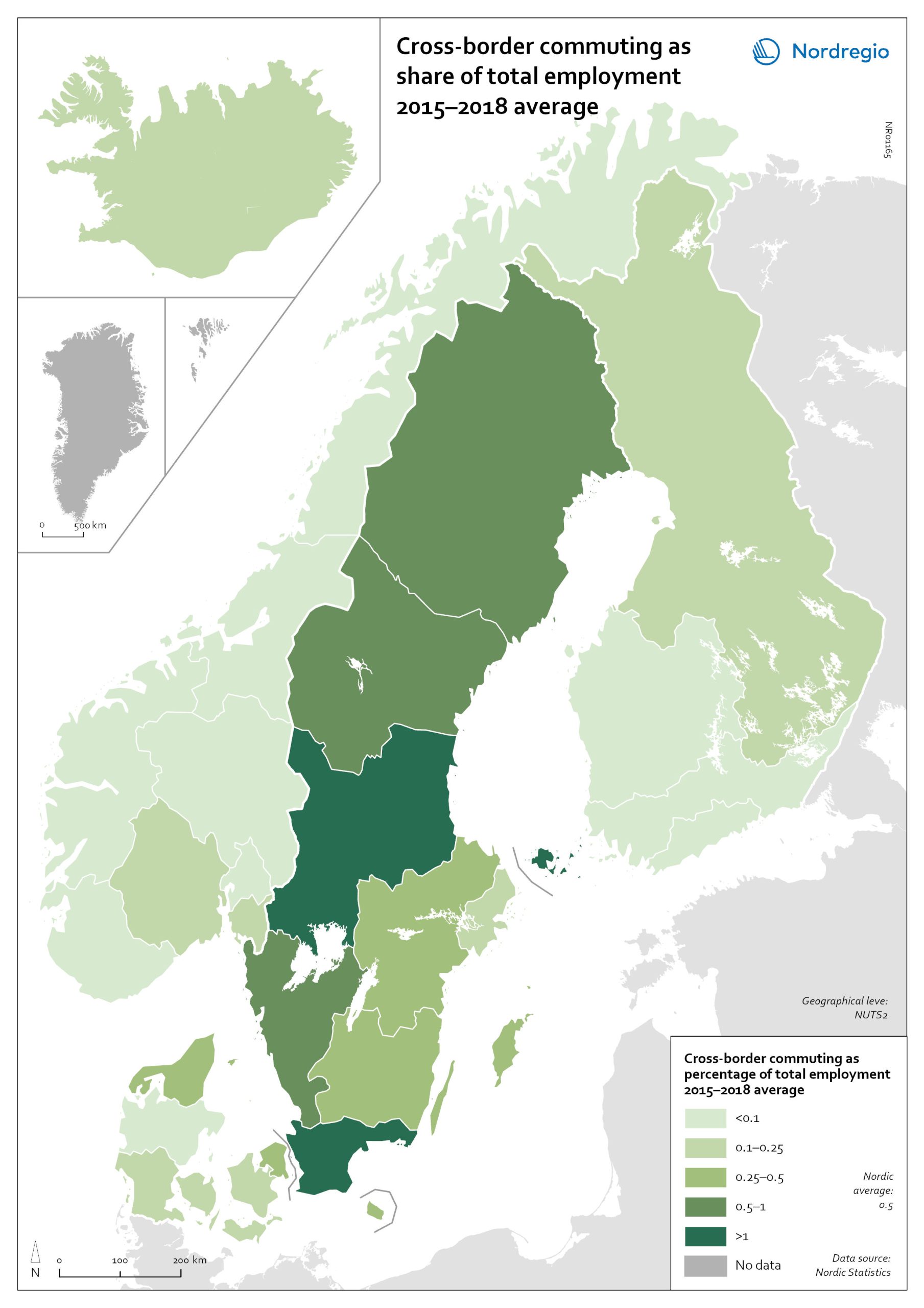

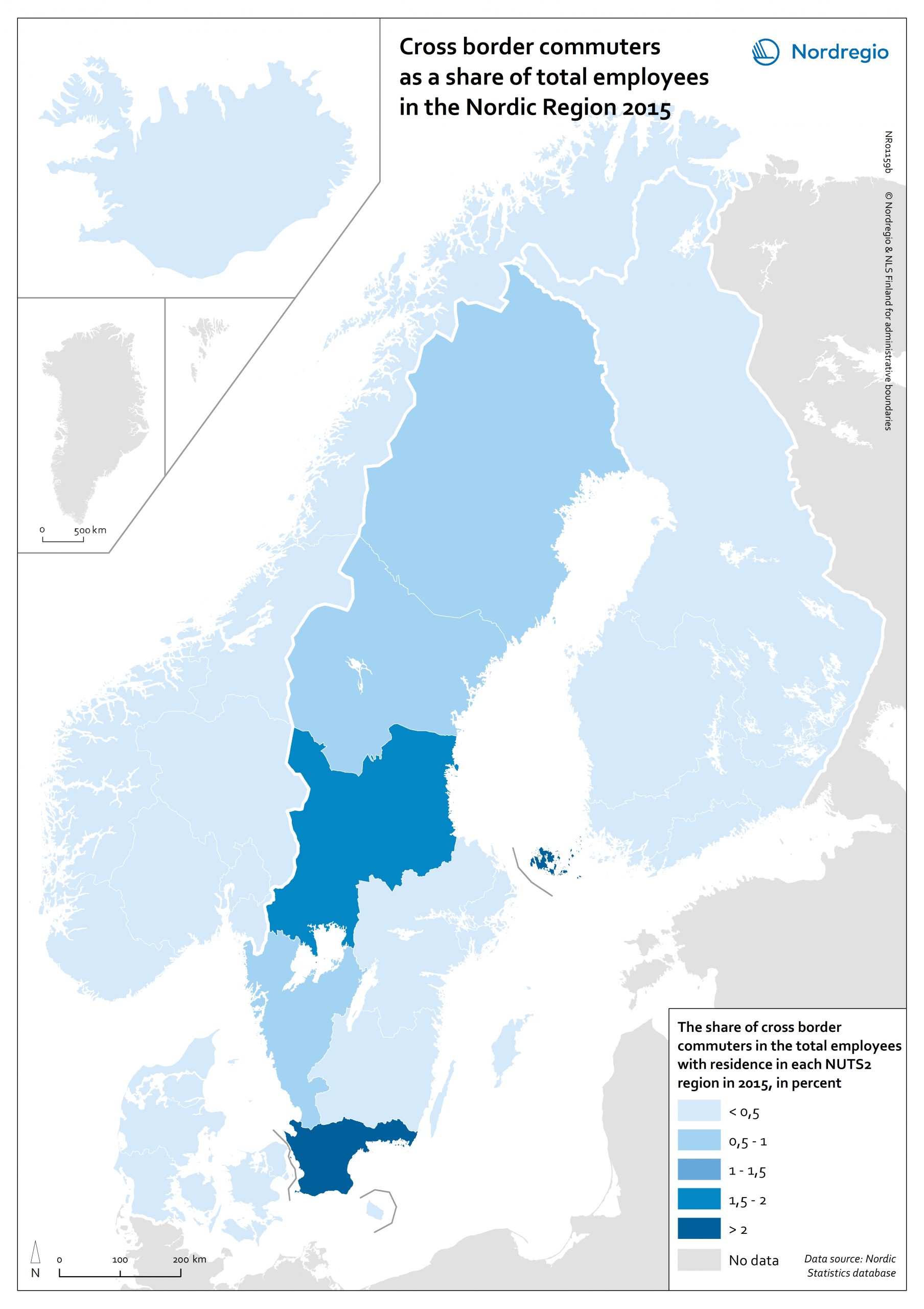

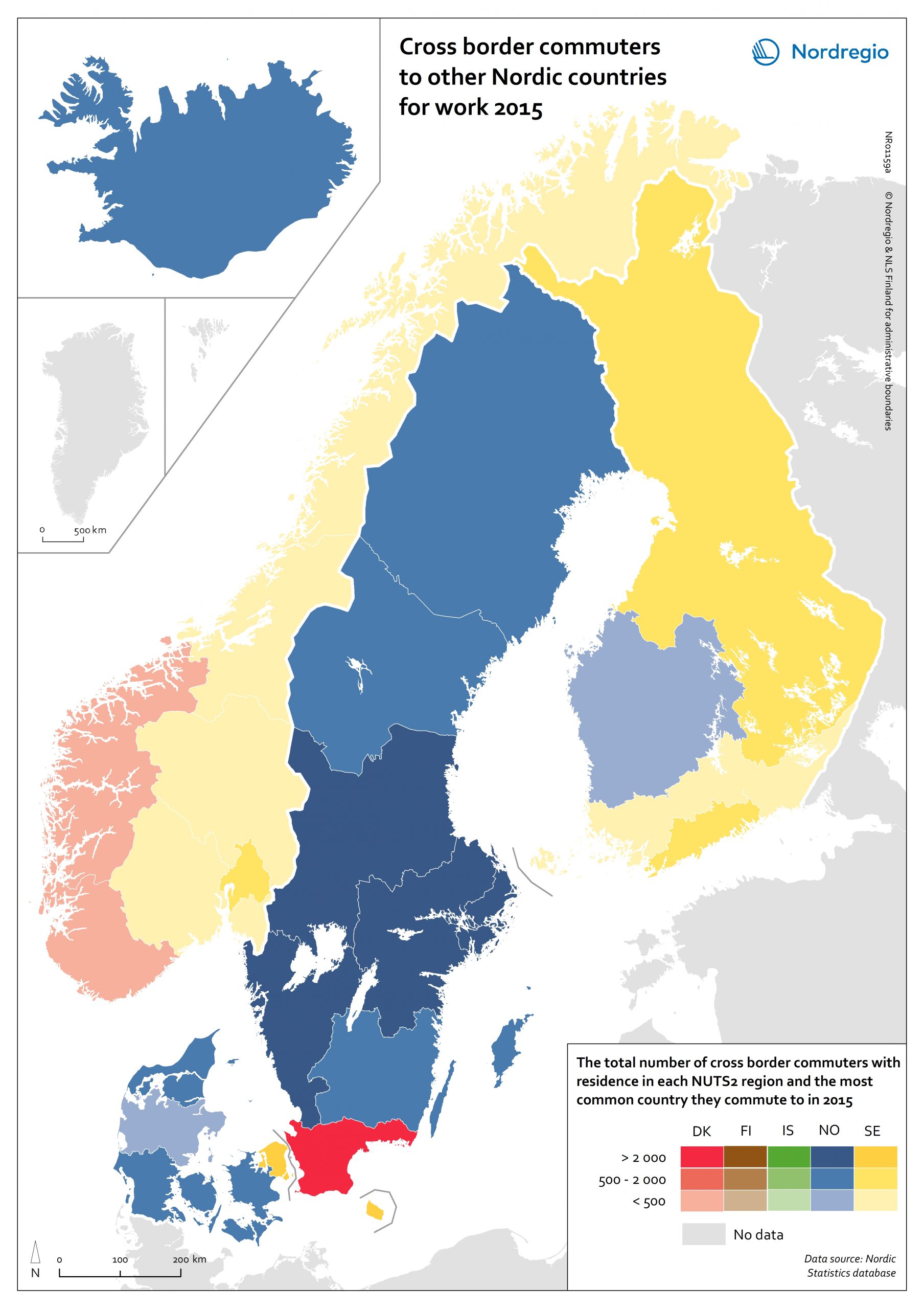

Cross-border commuting as share of employment

The map illustrates the average share of employees who commuted to another Nordic country between between 2015 and 2018 in Nordic regions (NUTS 2). Between 2015 and 2018, an average of approximately 49,000 people held a job in a Nordic country in which they were not residents. This indicates that, on average, 0.5% of the Nordic working-age population commuted to a job in another Nordic country. This is below the EU27 average of 1%, with the highest numbers found in Slovakia (5.1%), Luxembourg (2.8%) and Estonia (2.6%). Some of these people cross borders daily. Others work in another country by means of remote working combined with occasional commuting across borders. Within the Nordic Region, the largest cross-border commuter flows are in the southernmost parts of Sweden, regions in the middle of Sweden and in Åland, where more than 1% of the working population commutes to another Nordic country. However, there may be individual municipalities where cross-border commuting is substantially higher. For example, the employment rate in Årjäng Municipality, Sweden, increases by 15 percentage points when cross-border commuting is taken into account. These municipalities are not reflected on NUTS 2 level when averages are calculated. In terms of absolute numbers in 2015, the highest numbers of commuters were from Sweden: Sydsverige (16,543), Västsverige (7,899) and Norra Mellansverige (6,890). The highest number of commuters from a non-Swedish region were from Denmark’s Hovedstaden (2,583). Due to legislative barriers regarding the exchange of statistical data on cross-border commuting between the Nordic countries, more recent data is not available.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

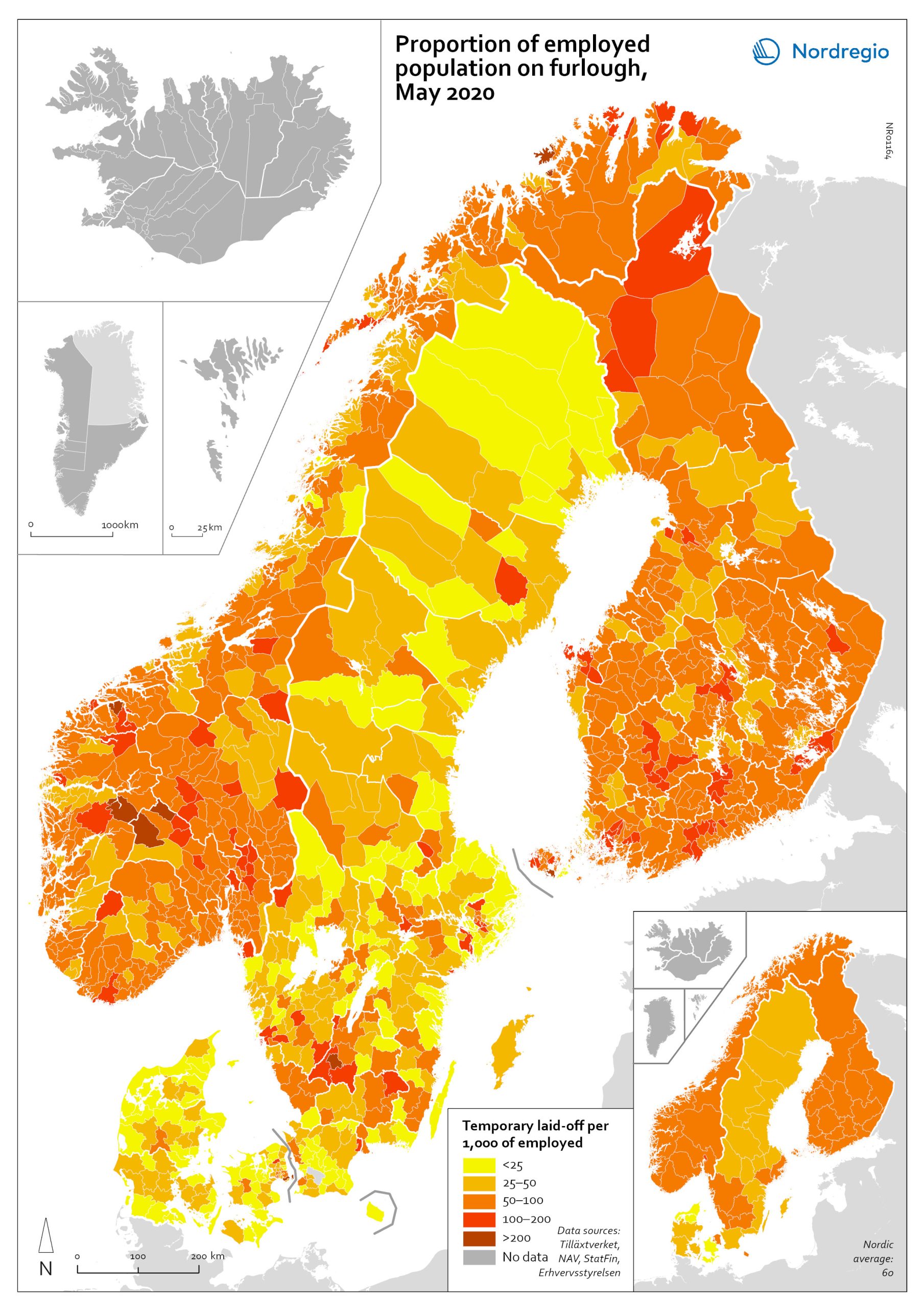

The share of laid-off employees at municipal and regional level

The map shows the share of employees laid off temporarily at municipal and regional levels in May 2020. According to the map, the highest proportion was in municipalities with a high proportion of people working in manufacturing, tourism and transport. These include the municipality of Sykkylven in Norway, which is home to several large furniture factories, the municipalities of Gnosjö and Oxelösund in Sweden, which both have multiple industries and a high proportion working in manufacturing, and the municipality of Taipalsaari in Finland, which is close to a large paper mill. Municipalities with significant tourism and a high proportion of employees laid off include Aurland, Hemsedal, Hol, and Trysil in Norway and Kittilä in Finland. The highly affected municipalities of Tårnby in Denmark and Härryda in Sweden are close to large airports, and in the municipality of Lemland in Finland, many people may work in the cruise industry. At regional level, the largest proportion of laid-off employees per 1,000 employed was in Oslo. All the other regions of Norway, all regions of Finland, and the regions of Halland, Jönköping, Kronoberg, Stockholm, Södermanland and Västra Götaland in Sweden and Hovedstaden in Denmark also had relatively high shares. The lowest proportions were found in the regions of Nordjylland and Sjælland in Denmark.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

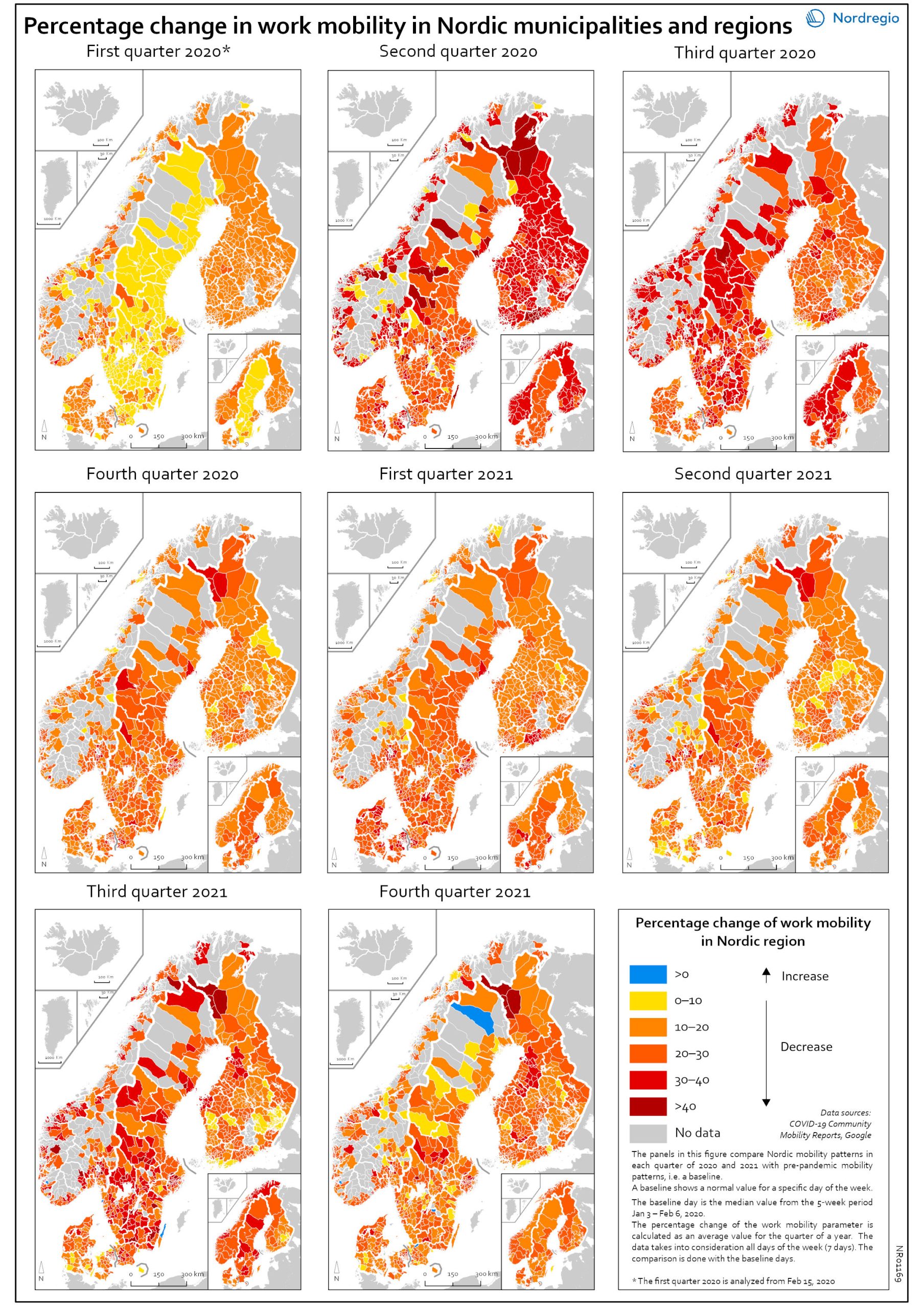

Work mobility per municipality and region by quarter

The map shows the percentage change for work mobility in Nordic regions and municipalities compared to a pre-pandemic baseline. The maps compare Nordic mobility patterns in each quarter of 2020 and 2021 with a pre-pandemic baseline. Based on Google data, the panels illustrate the impact of national restrictions and how those restrictions hampered work mobility. As the restrictions were both national and regional in nature, some regions and municipalities were more affected than others. The darker areas in the map show that work mobility decreased the most Q2 and Q3 2020 and in Q3 2021. The panels also show that mobility decreased later in Sweden than in the other Nordic countries. However, the decrease in Q3 in both 2020 and 2021 may partly be explained by the summer vacation months, when work mobility tends to decrease anyway. In Q4 2021, the overall situation seems to improve, although the pattern is mixed. In a few municipalities the situation is almost back to pre-pandemic baseline while in most municipalities, there is still less mobility in the labour market compared to the pre-pandemic situation.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

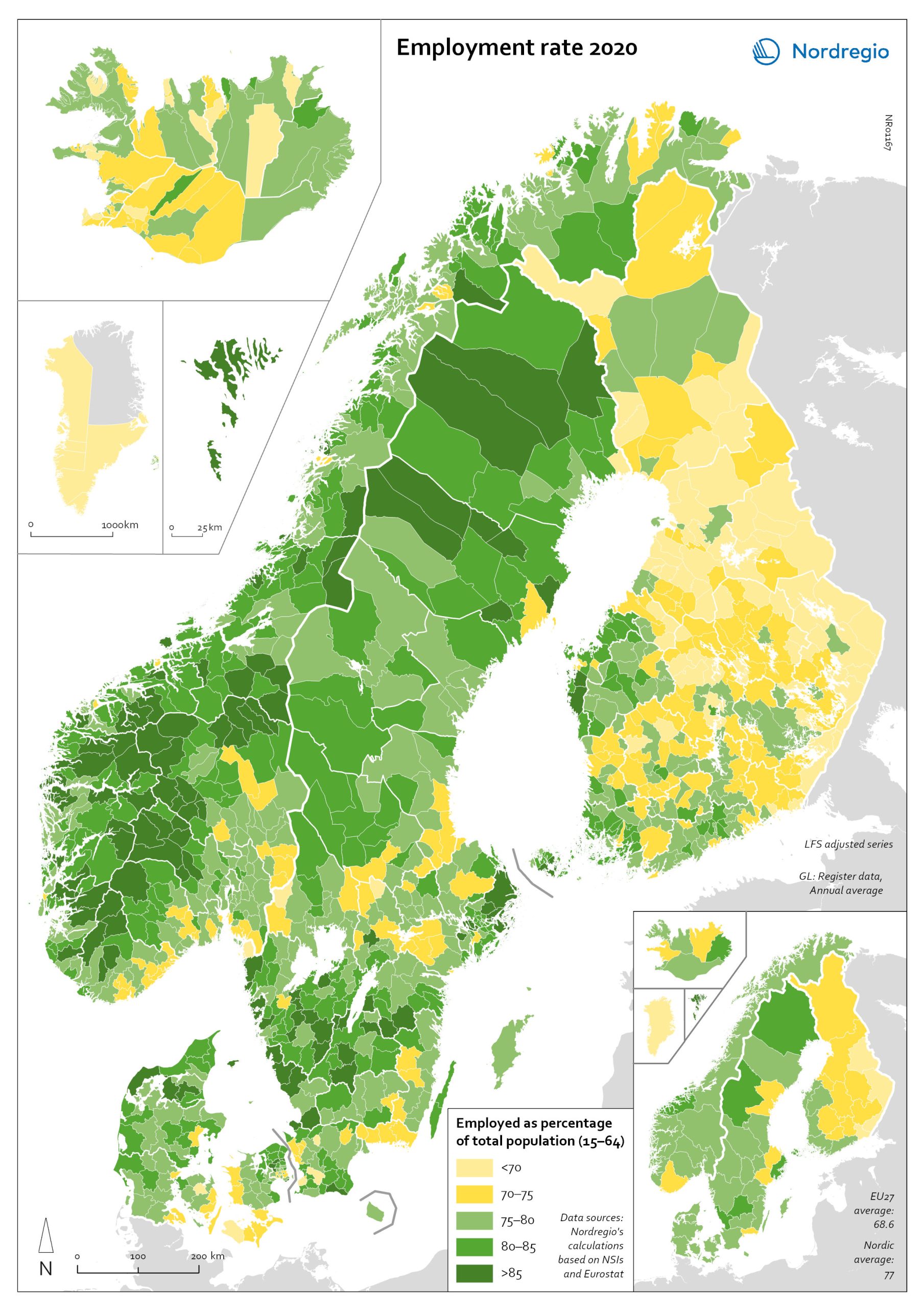

Employment rate 2020

The map shows the employment rate for all Nordic municipalities and regions in 2020. Full employment is one of the cornerstones of what is known as the Nordic model and, historically, the Nordic countries have enjoyed comparably high employment rates, particularly for women and older workers. The employment rate measures the number of people in work as a proportion of the working-age population (aged 15–64) as a whole. The green tones indicate municipalities with employment rates above 75% in 2020, with the darker green representing higher employment rate. The yellow tones indicate municipalities with employment rates below 75% in 2020. The light-yellow colour indicates municipalities with employment rates below 70% in 2020. The highest employment rates were found in the Faroe Islands and in many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden, whereas the lowest employment rates were in Greenland and several municipalities in Finland. At regional level, the Faroe Islands, the regions of Halland, Jämtland, Jönköping, Norrbotten and Stockholm in Sweden, and the region of Møre og Romsdal in Norway had an employment rate above 80%. Employment rates below 70% were recorded in Greenland and the regions of Etelä-Karjala, Kainuu, Kymenlaakso and Pohjois-Karjala in Finland.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

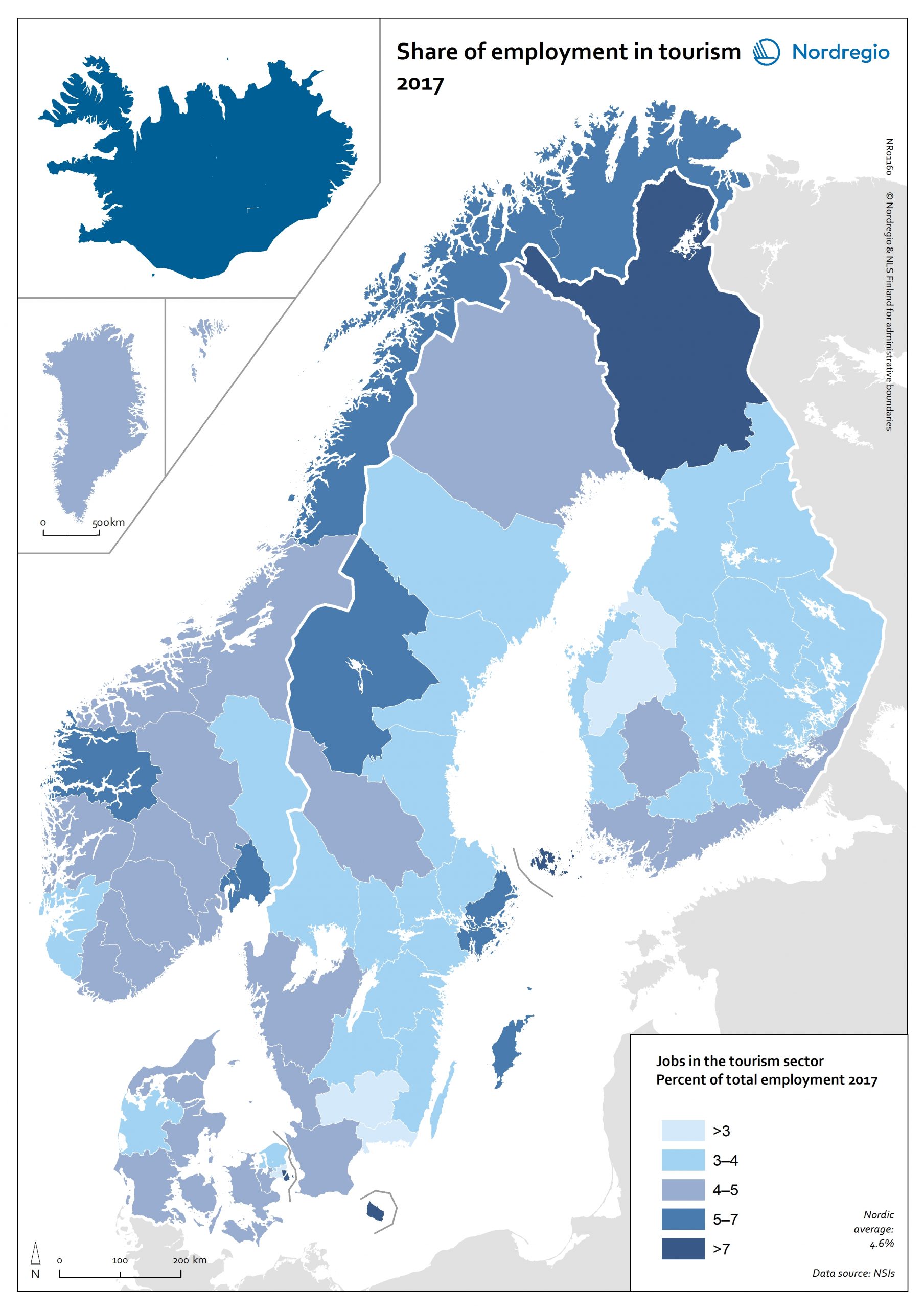

Share of employment in tourism 2017

The map shows the share of employed people in tourism industry in 2017. On a national level the share of tourism is quite similar in the Nordic countries, except for Iceland where the share is more than double as high. In Iceland it is especially the sector “Accommodation and food service activities” that stands out. This category alone stood for 6.9% of the total employment in Iceland in 2017 . On a regional level Åland stands out with 14.7% of employment in tourism. In Åland it is mainly the category “Sea passenger transport” that is big. Only this category stands for 9.8% of the employment. Also other islands such as Gotland and Bornholm have a high share of employment in tourism as well as the capital cities of Copenhagen and Stockholm. Jämtland attracts many tourists in the winter. The regions with the lowest share of tourism employment include the Finnish regions Keski-Pohjanmaa and Etelä-Pohjanmaa (both 2,7%); Københavns omegn (2.9%) and Vestjylland (3.4%) in Denmark; Blekinge (3.3%) and Kronoberg (3.3%) in Sweden and Østfold (3.5%) in Norway. The data on employment by sector is classified using the NACE classification system (“nomenclature statistique des activités économiques dans la Communauté européenne”). To define which sectors that tourism comprise of, we have selected the Eurostat’s definition due to the fact that Eurostat has adapted the definition of UNWTO to a European context to make it more precise and to avoid overestimate certain economic activities (e.g. real estate activities). Their definition is also very close to the definition used by Tillväxtverket. Eurostat thus defines tourism as comprising the following economic activities : H4910 Passenger rail transport, interurban H4932 Taxi operation H4939 Other passenger land transport n.e.c. H5010 Sea and coastal passenger water transport H5030 Inland passenger water transport H5110 Passenger air transport I5510 Hotels and…

2021 February

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

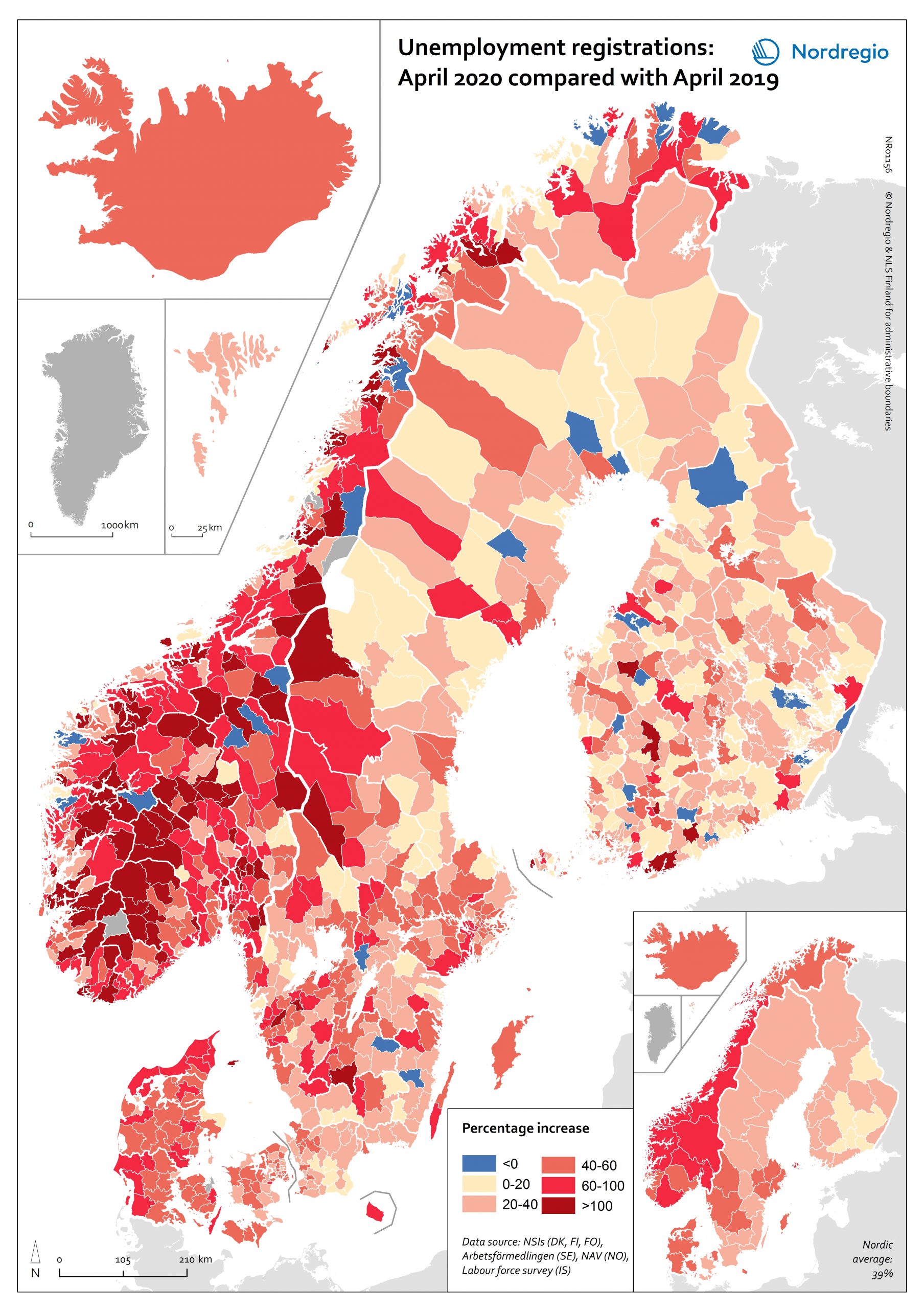

Labour market impacts of COVID-19

On May 17, 2020, 94% of the world’s workers were living in countries with some form of workplace closure measures in place (ILO, 2020). While it is too early to make predictions about the long-term consequences of this, it is possible to make some observations about the short-term labour market impacts in the Nordic Region. The map shows the number of people who registered as unemployed in April 2020 compared with the number of people who registered as unemployed in April 2019 at the municipal level for Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden and Åland Islands and at the national/territory level for Iceland and the Faroe Islands. The shading represents the increase in percent, with darker colours showing higher relative increases compared to the previous year and lighter colours lower relative increases. Municipalities shaded in blue on the map did not experience an increase in unemployment registrations in April 2020 compared to April 2019. Overall, the number of unemployment registrations across the Region was 38.9% higher in April 2020 than in April 2019. This increase equates to a total of 220 354 Nordic workers and has affected almost all Nordic municipalities and regions to some degree. Proportionally speaking, Norway saw the largest increase (69%), followed by Iceland (59%), Denmark (48%), Sweden (41%), and Finland (24%). Though between-municipality variation is evident, the greatest differences appears to be between countries. Interestingly, many Swedish municipalities along the southern coast between Sweden and Norway saw increases more consistent with the overall trend observed in Norway. This may be a reflection of the prevalence of cross-border commuting in these regions. It is important to note that the labour market situation in April 2019 has some baring on the results shown on the map. For example, the appearance of a sharper relative increase in Norway is primarily…

2020 October

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

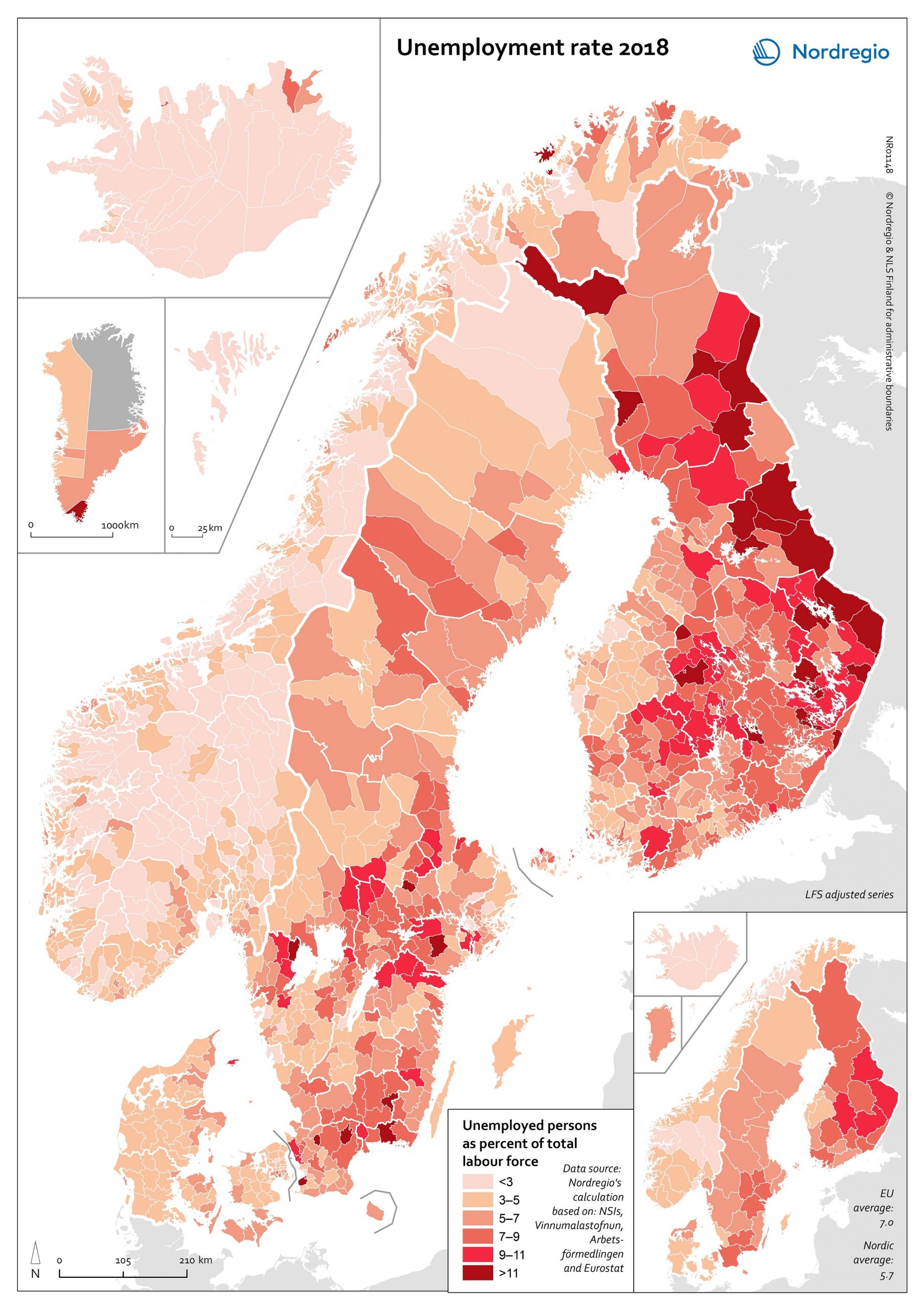

Unemployment rate 2018

The map shows the unemployment rate in the Nordic counties at the municipal level in 2018. Unemployment is measured as the total number of unemployed (i.e. people who were not in employment, but seeking job and available to take up an employment) as share of the total workforce (i.e. employed plus unemployed). The map is based on data from the labour force survey, which is the official way of measuring unemployment. In order to show the municipal level register data has been used as an allocation key. The lighter shades on the map represent lower levels of unemployment, and the darker shades represent higher levels. The Nordic Region has a low average unemployment rate (5.7%) compared with the EU average (7.0%). There is, however, substantial regional variation, both within and between countries. The lowest unemployment rates are found in Iceland, Norway and the Faroe Islands. The highest rates can be found in Finland (particularly in the east ern municipalities), parts of southern Sweden, and Kujalleq (Greenland). Unemployment rates in Den mark are higher than those found in Iceland and Norway, but lower than those found in Sweden and Finland – with the highest rates found in Nord Jylland. The unemployment rate also varies between population groups. In all Nordic countries, for ex ample, the foreign-born population are more likely to be unemployed than their native-born counter parts, particularly if they were born outside the EU (see Figure 4.5). This trend is most pronounced in Sweden and Finland. It can also be observed throughout the EU, where unemployment for foreign-born persons is more than twice that of the native-born population.

2020 October

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

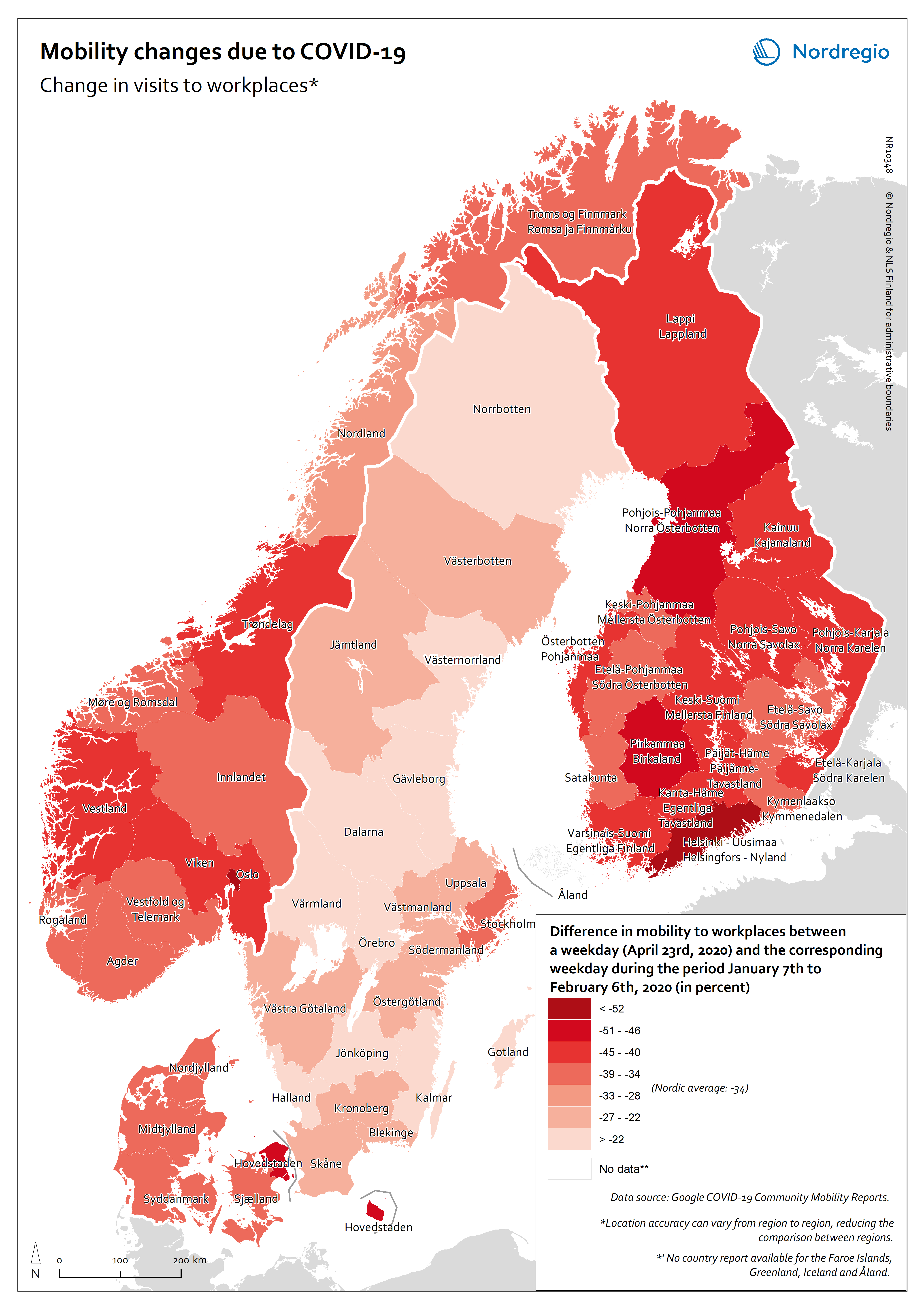

Mobility changes due to COVID-19

This map shows the difference in mobility to workplaces between a weekday (April 23rd, 2020) and the corresponding weekday during the period January 7th to February 6th, 2020 (in percent). The data highlights the percent change in visits to workplaces within each administrative region in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Data is not available for the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland and Åland. Read more about the data here. The average value of the Nordic regions included in the map is a reduction by 34% of the number of visits to workplaces on April 23rd (in comparison to a baseline). This average value hides large variations within the Nordic Region with the most modest change occurring in Gotland (-12%) and the most severe change in Oslo (-57%). More generally, variations can be identified both between and within countries. The variations between countries reveal differences in recommendations and restrictions from published by the different national governments. Details for each country have been gathered by Info Norden and can be found here. As a result, the change in visits to workplaces decreased by 26% in Sweden, 39% in Denmark, 41% in Norway and 47% in Finland. The variations within countries also reveal differences in government´s decisions (e.g. lockdown of the Helsinki-Uusimaa region reducing the mobility to workplaces by 53%), but not only. There are indeed a number of local characteristics of the labour markets that contribute at explaining that the largest changes in mobility to workplaces are found in capital city regions. These local characteristics are a greater dependency on public transport for commuters, who are adviced to avoid using such means of transportation under the COVID-19 context; and having a higher share of jobs that can be done by teleworking, among others.

2020 May

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Others

- Transport

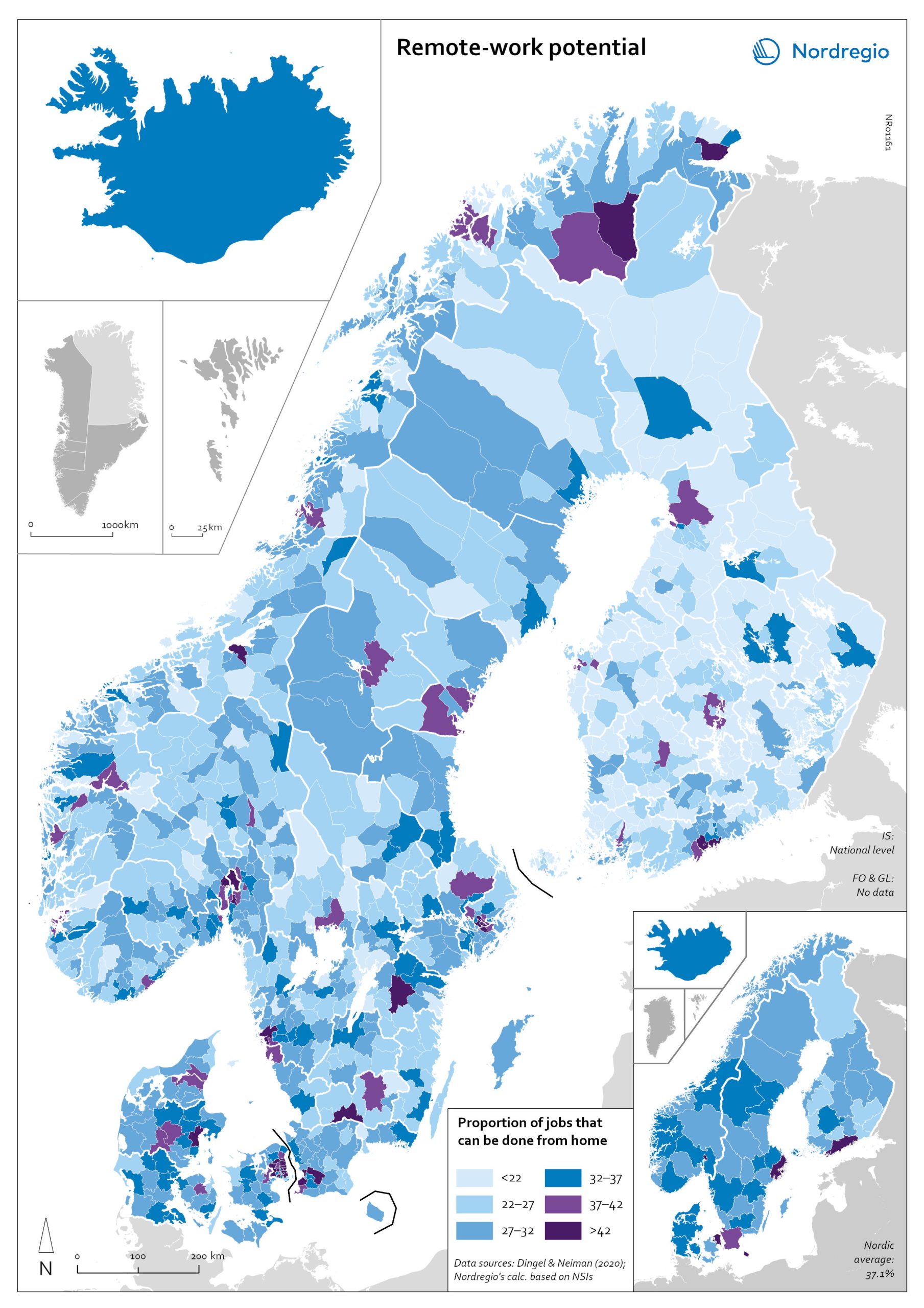

Nordic local labour market areas 2018

This map shows the Nordic local labour market areas (LLMAs) in 2018, based on their size (number of municipalities) and whether the employment rate was above or below 75%. The data analysis to calculate LLMAs is based on national statistics on the employed day population (i.e. places of employment), the employed night population (i.e. employed residents) and commuting over municipal borders, as municipal divisions at 1 January 2019. For Norway, the data was from 2018, for Denmark and Sweden from 2017, for Finland from 2016 and for the Faroe Islands from 2011. In Greenland, due to the large distances between municipalities, there is no daily commuting over municipal borders. Iceland lacks commuting statistics; therefore, the Icelandic LLMAs were delineated based on a study of commuter areas by the Icelandic Regional Development Institute (Byggðastofnun, 2015). The delineation of the LLMAs was based on the methodology that comprised the following steps: • LLMA centres should fulfil the conditions that: 1) the share of out-commuters from a municipality is no more than 20% of its employed night population, OR 2) the employed day population of a municipality is higher than its employed night population AND 3) the highest single out-commuting flow to another municipality is not more than 10% of its employed night population. • Municipalities belonging to an LLMA should have a single out-commuting flow to another municipality that is more than 7.5% of its employed night population. • LLMA secondary centres should fulfil the conditions that: 1) the share of out-commuters of a municipality is not more than 25% of its employed night population AND 2) the highest single out-commuting flow to another municipality is not more than 7.5% of its employed night population AND 3) the municipality has its own LLMA by having other municipalities that belong to it. There…

2020 February

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

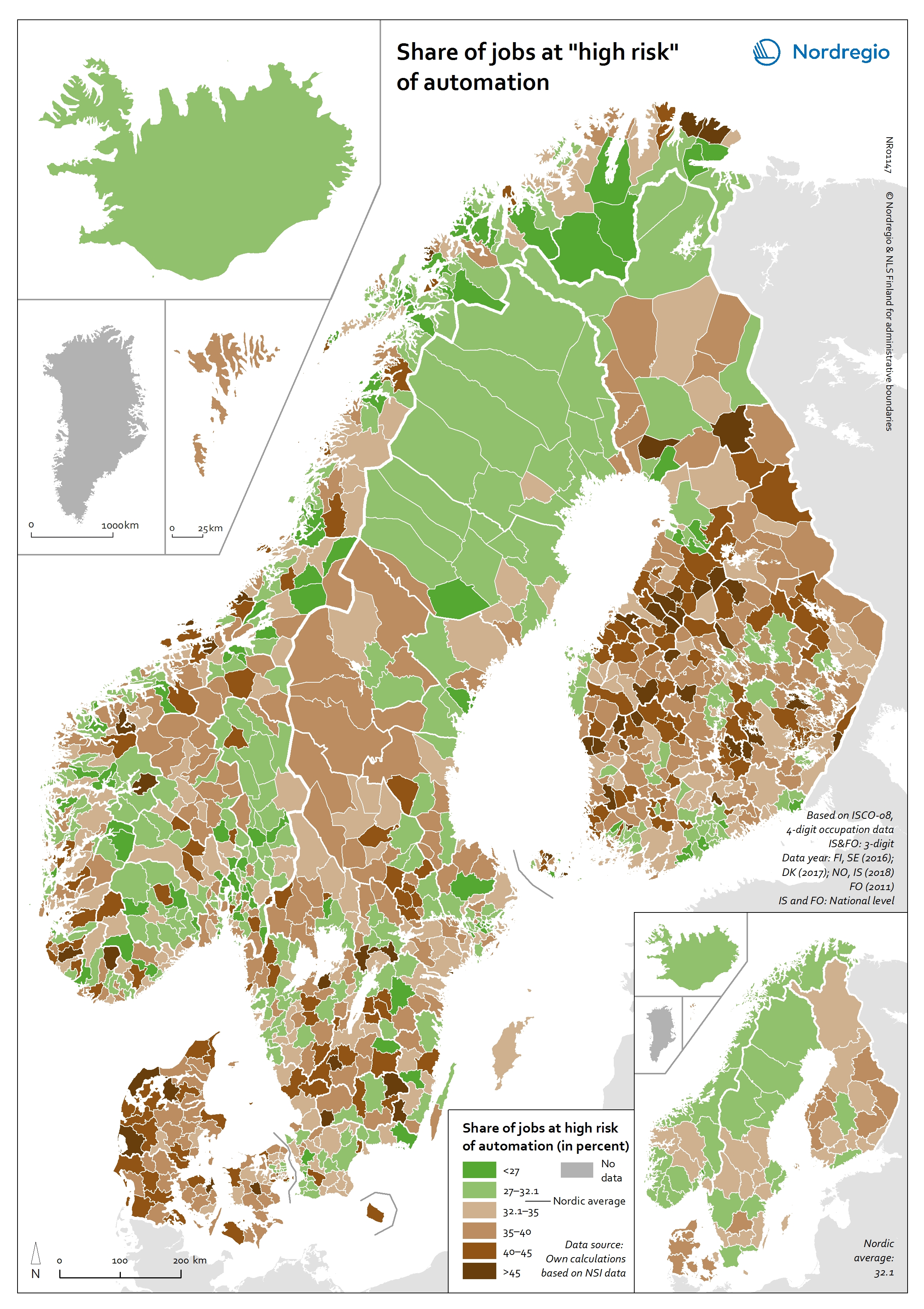

Share of jobs at “high risk” of automation

This map shows the share of jobs at “high risk” of automation at the municipal level The map shows the share of jobs at “high risk” of automation based on the methodology of Frey and Osborne as outlined in the paper “The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?” (2017). The green areas show a share of jobs at “high risk” of automation below the Nordic average (32.1%) and the brown areas a share above the Nordic average. Based on Frey and Osborne’s methodology, approximately one third (32.1%) of Nordic jobs are considered at “high risk” of automation in the next one to two decades. This means that 32.1% of jobs in the Nordic Region fall above the 0.7 threshold identified by Frey and Osborne (with 0 meaning no automation potential and 1 meaning complete automation potential). Although this is significantly lower than the figure revealed by Frey and Osborne in the US context (47%) it still raises cause for concern. Faroe Islands has the highest portion of jobs at risk (38.7%) followed by Denmark (36.7%), Åland (36.3%), Iceland (32%) and Finland (31.9%). Norway (29.9%) and Sweden (30.9%) have the lowest number of jobs in the high-risk category. At the municipal level, the municipalities with the highest share of jobs at high risk of automation are Pyhäntä (58%), Kyyjärvi (58.1%) and Lestijärvi (56.9%) in Finland; Gnosjö (51%) and Hallsberg (50%) in Sweden; and Snillfjord (49%) in Norway. In these municipalities, a large proportion of the workforce are employed in a specific occupation, for example, carpenters and joiners in Pyhäntä, machine operators in Kyyjärvi and Gnosjö, and livestock and dairy producers in Lestijärvi. Another thing that these municipalities have in common is that they are all rural. The municipalities with the lowest share of jobs at high risk of…

2020 February

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

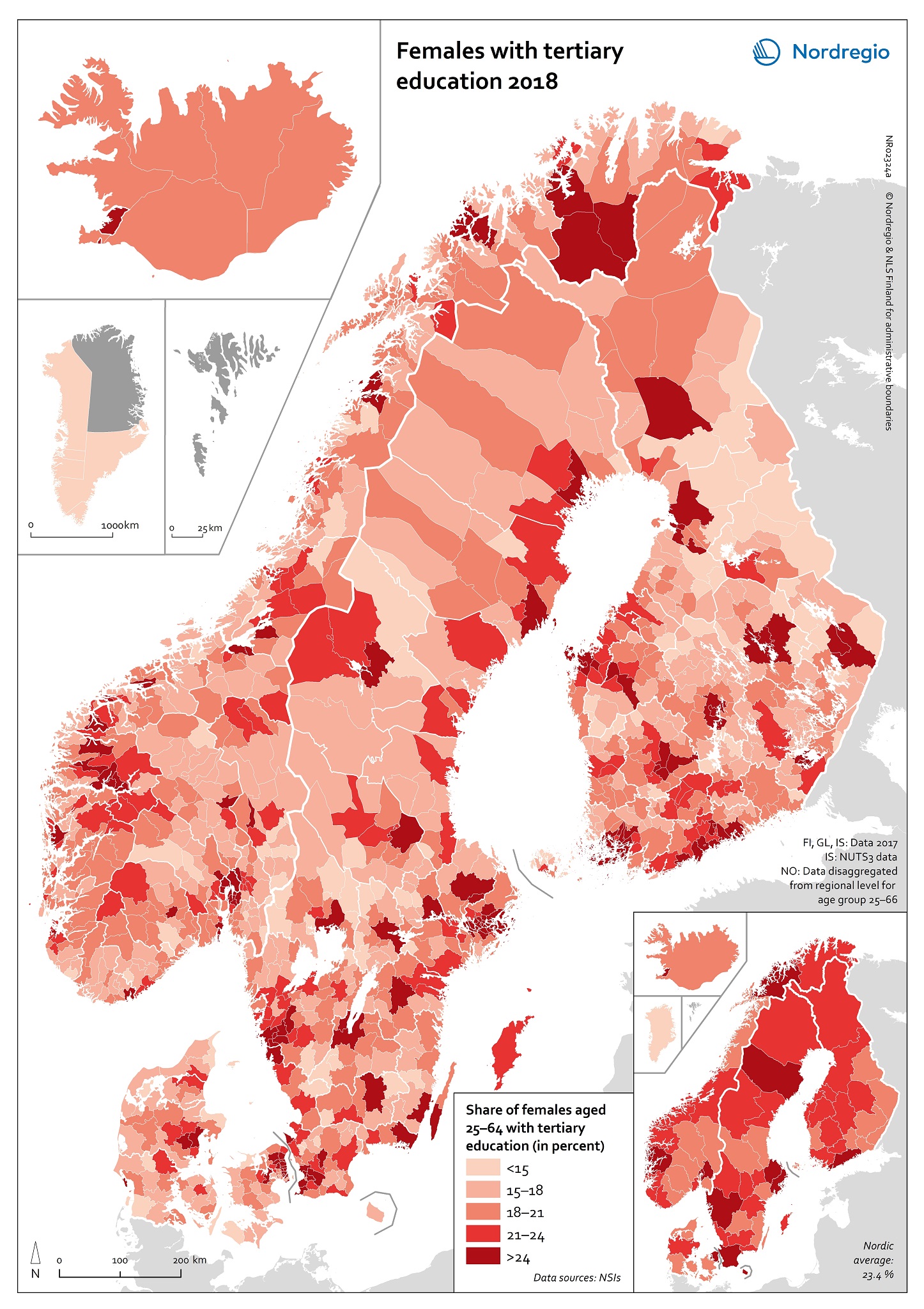

Females with tertiary education 2018

This map shows the number of females aged 25-64 with tertiary level educational attainment as a share of the total population aged 25-64 in Nordic municipalities and regions. In the Nordic countries, the educational level is generally high. Attainment of at least an upper secondary education for the adult population in all Nordic countries exceeds the average in OECD and in Finland it is as high as 87.9 %. The population with tertiary education is well above the EU average in Nordic countries. It has increased from around 33% in Finland, 25% in Norway and Denmark, and 20% in Sweden at the beginning of the 1990s, to 40–45% 20 years later. Darker red indicates higher a higher share of women with tertiary level education. Most people with higher education live in predominantly urban and university regions. The explanations for this can be found in the economic geography of these regions, which are comprised of universities and knowledge-intensive companies attracting research and high skilled labour. See also map showing male attainment level. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

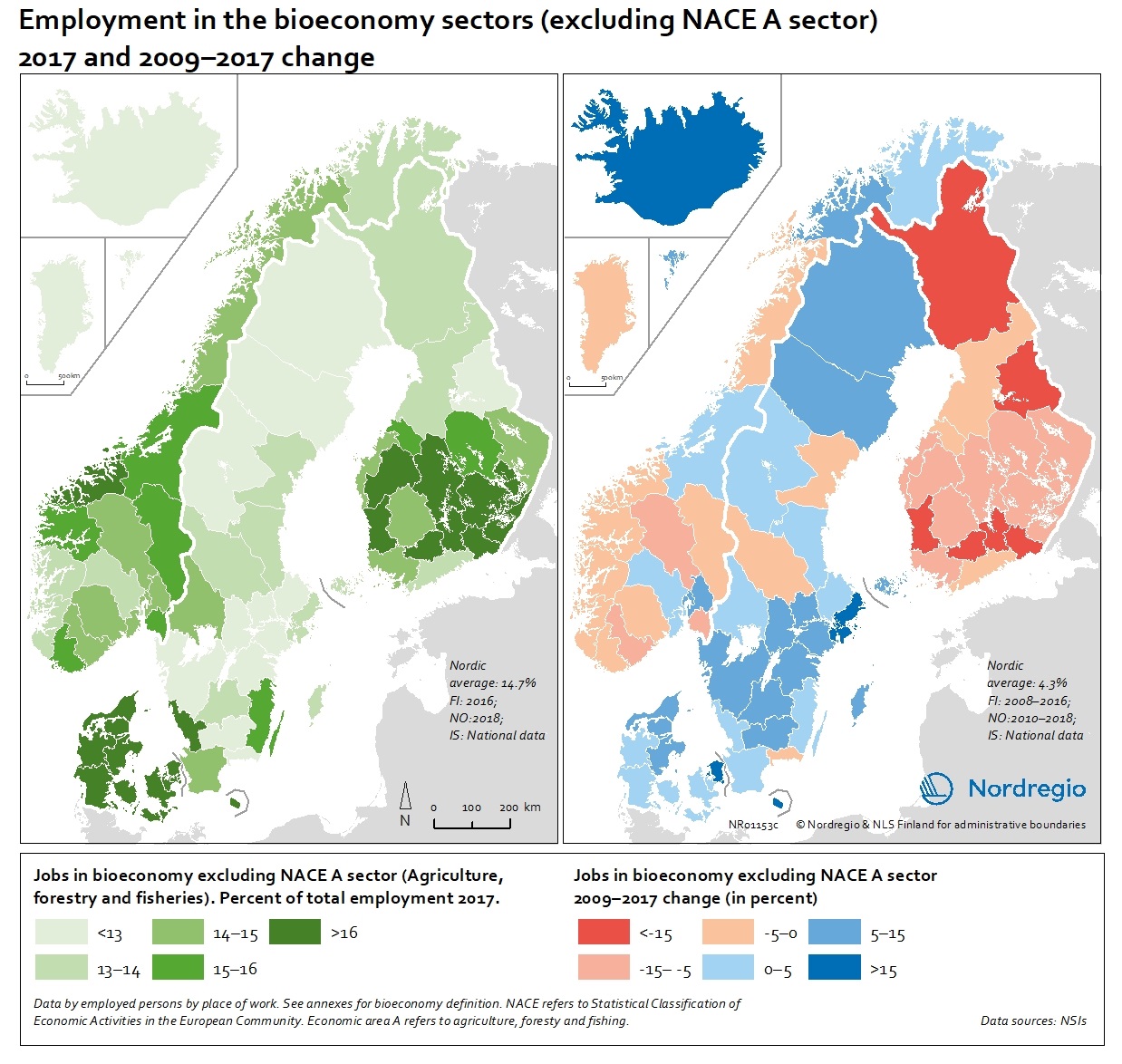

People employed in the bioeconomy excluding NACE sector A in 2017 and 2009-2017 change

These maps show the number of jobs in the bioeconomy sectors as a share of the total employment in 2017 (left) and 2009-2017 change (right), excluding the NACE A sectors. The non-NACE-A sectors have seen a more moderate decrease in Finland but a noticeable increase in most parts of Sweden, Denmark and the Faroe Islands and a remarkable increase in Iceland with more than 15% (Figure 9.3). The average increase in the Nordic Region is 4.3% in the non-NACE-A sectors. There are also notable differences within the countries, showing that regional differences matter. In Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands, there is a positive trend in most regions, but in Finland, almost all regions are losing jobs in the primary industries. In Norway and Sweden, some regions show positive development while others are in decline. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

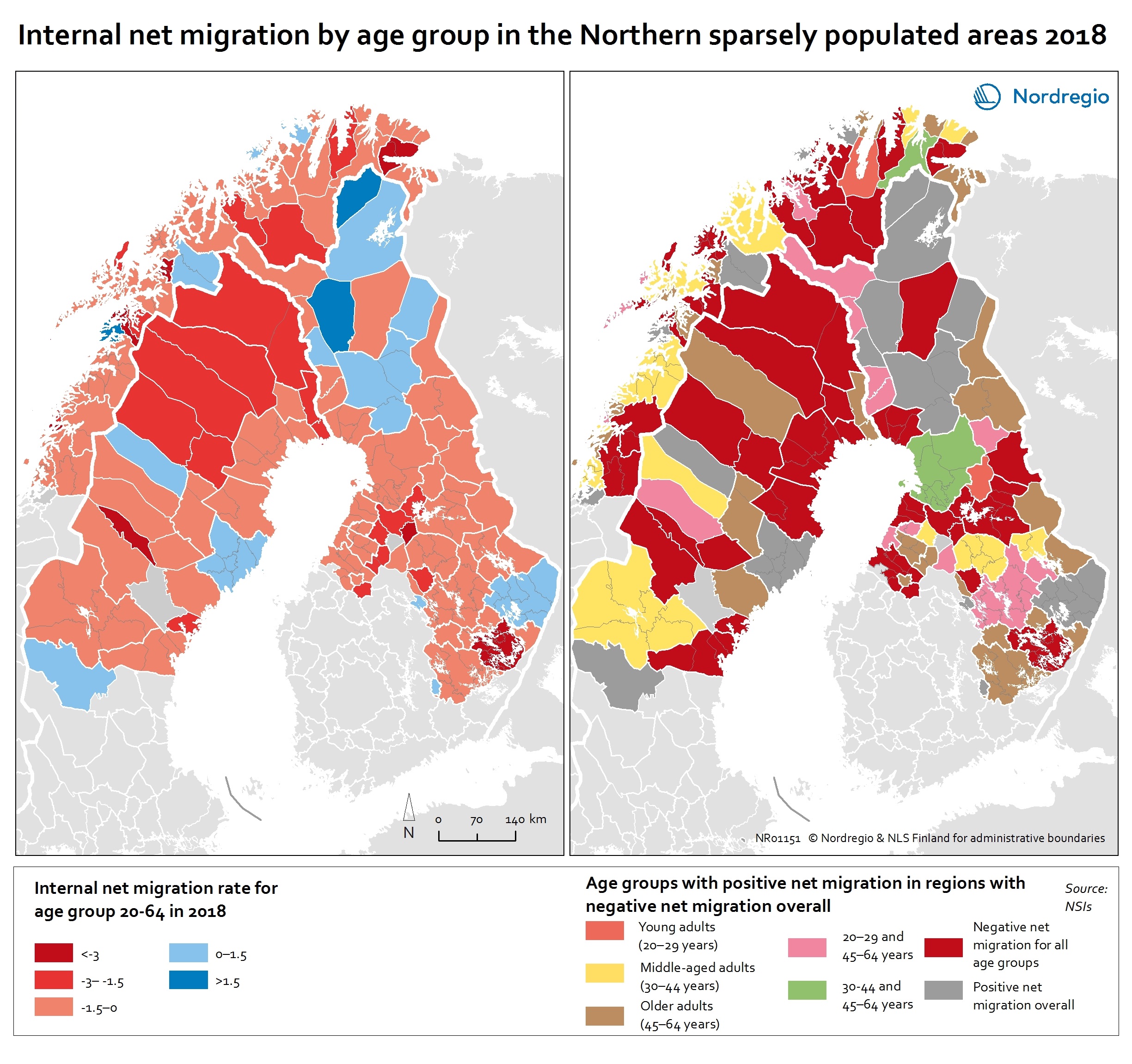

Internal net migration by age group in the Northern sparsely populated areas 2018

This map shows the internal net migration rate in 2018 (left map) and net migration by age group (right map) in local labour market areas of the Northern sparsely populated areas in 2018 The map on left shows the internal net migration rate in the NSPAs in 2018. Although many regions experienced negative net migration, this was not the case for all segments of the population. The map on the right of shows the age groups in which more people moved in than moved out, despite these regions having negative net migration overall. The red colours on the map on the left indicates a net out-migration, while the blue colours indicate a positive net migration. In the map on the right, the red colours indicate net out-migration for all age groups and the grey positive net migration overall. The other colours indicate age groups with a positive net migration (while having negative net migration overall). Inward and outward migration are slightly different in the local labour market areas (LLMAs) compared to the independent labour markets. Among the LLMAs, Rovaniemi is the only one that has positive net migration in all age groups. This positive development may be due to the number of governmental offices, the strength of the tourism industry and the presence of two universities. On the contrary, 18 local labour market areas– four in Sweden, nine in Norway and five in Finland – have negative net migration in all age groups. Out-migration of young adults is seen in most of LLMAs, the exceptions being Umeå, Målsev, Joensuu and Oulu. The inflows of young adults in these regions reflect the presence of the universities in Umeå, Joensuu and Oulu and the army bases in Målselv. Despite this positive inflow, most of these LLMAs are unable to retain adults in…

2020 February

- Demography

- Labour force

- Migration

- NSPA and North Atlantic